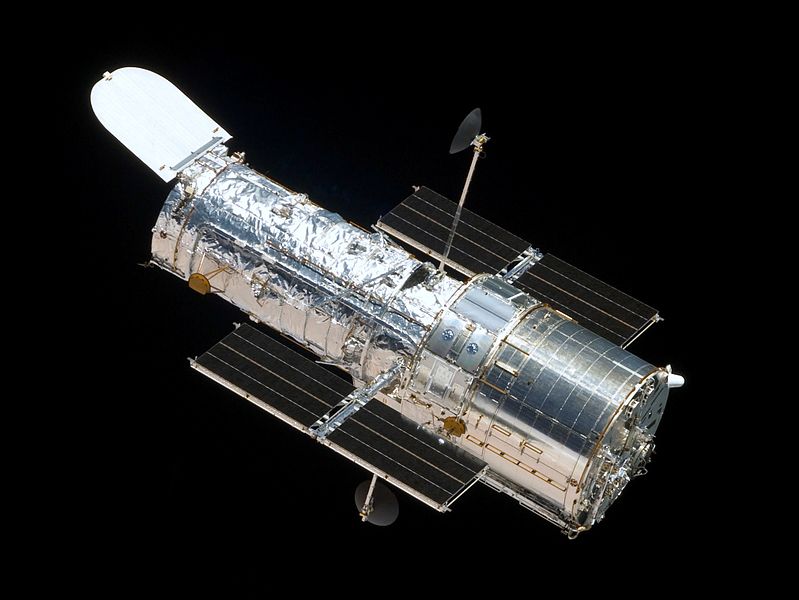

One of the rituals of observational astronomy is the application for telescope time. Once, twice, or three times per year, observatories around (and even above!) the world solicit proposals for the best use of their telescopes. Each observatory has its own rules on who can apply for time. Private observatories, like Keck, Palomar, Lowell, and McDonald, restrict access to partner institutions and staff (though some reserve a small amount of time for “public” access). National facilities, like those at Kitt Peak National Observatories, are open to all astronomers (though there may be some restrictions on foreign proposals), and in particular anyone in the world may apply to time on the Hubble Space Telescope. National facilities and institutions also purchase or trade for small amounts of time on private telescopes; for instance, I apply to time on the Keck telescopes (which are private to the Universities of California and Caltech) through a small amount of time that NASA purchases to pursue narrow science goals in support of its space missions.

Different telescopes offer different instruments with different capabilities, and so astronomers seeking to answer a particular astronomical question need to determine which facilities can meet their needs. Here at Penn State, we have access to about 25% of the time on the

Hobby-Eberly Telescope, which I regularly apply for time on. We also have a small share of the

South Africa Large Telescope (SALT), and have “preferred” access to the public time offered at McDonald Observatory. We also manage the

Swift spacecraft, which many Penn State astronomers have programs on.

With HET I use the iodine cell in the high resolution spectrograph to collect radial velocity measurements of bright, nearby stars. I propose for time through Penn State’s Time Allocation Committee, or TAC (which I have sat on, though naturally I must recuse myself from discussions of my own proposals!). Penn State’s TAC decides which proposals from Penn State faculty and staff are good uses of this limited resources by reading all of the proposals, judging the likelihood of success, the scientific merit of the observations, the track record of the proposer, and the amount and quality of the time requested. The proposals are then awarded time in ranked order until Penn State’s entire share for the trimester is exhausted.

This year, my student and postdoc also applied for some of the public time at McDonald Observatory to use their

2.7-m telescope’s coud� spectrograph to get high resolution spectra. Dr. Ming Zhao would like to observe the bright star sigma Draconis, a common precise velocity standard target, at very high resolution to determine its spectrum to exquisite accuracy. This will help us diagnose systematic errors in our velocity reduction pipeline. My student Jason Curtis wants to observe some stars in the cluster

Ruprecht 147 that are too far south for HET to observe.

This April I will head back down to Tucson to judge proposals sent to the

National Optical Astronomical Observatory (NOAO) for use of the national facilities, including the Kitt Peak telescopes, the

Gemini telescopes, telescopes at

Cerro Telolo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, and a few other facilities that NOAO has purchased or traded for small amounts of time on. I sit on the

Solar System TAC, meaning that we read the proposals for observations of objects in the Solar System. This is a bit outside my field, but this is also the TAC that judges proposals to look for or characterize exoplanets, so they need expertise on this subject, too. I have learned a lot about comets, asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects, and planetary atmospheres, in the last few years!

Serving on TAC’s is a lot of work, but it is important service and has to be done well. It is important that good science and ideas be rewarded and that facilities are used to maximize their scientific potential. Perhaps the hardest part is explaining to those who did not get time what concerns or problems put their proposal below the successful ones; this can be very difficult when there are many more excellent proposals than time to be handed out, because there may be no strong reason to pick one over another! In those cases you have to admit to having made a hard choice based on some small, almost inconsequential demerit.

Everyone who applies regularly for time has stories of their brilliant ideas that were unjustly under-appreciated, misunderstood, or even unread by the TAC members, and of the ludicrous TAC reports they have received, which reveal the TAC members to be lazy, unread ignoramuses. I have several. The only antidote I can offer: fix the problem by agreeing to serve on a TAC and do it very well! It will make astronomy better.

This April I will head back down to Tucson to judge proposals sent to the National Optical Astronomical Observatory (NOAO) for use of the national facilities, including the Kitt Peak telescopes, the Gemini telescopes, telescopes at Cerro Telolo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, and a few other facilities that NOAO has purchased or traded for small amounts of time on. I sit on the Solar System TAC, meaning that we read the proposals for observations of objects in the Solar System. This is a bit outside my field, but this is also the TAC that judges proposals to look for or characterize exoplanets, so they need expertise on this subject, too. I have learned a lot about comets, asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects, and planetary atmospheres, in the last few years!

This April I will head back down to Tucson to judge proposals sent to the National Optical Astronomical Observatory (NOAO) for use of the national facilities, including the Kitt Peak telescopes, the Gemini telescopes, telescopes at Cerro Telolo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, and a few other facilities that NOAO has purchased or traded for small amounts of time on. I sit on the Solar System TAC, meaning that we read the proposals for observations of objects in the Solar System. This is a bit outside my field, but this is also the TAC that judges proposals to look for or characterize exoplanets, so they need expertise on this subject, too. I have learned a lot about comets, asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects, and planetary atmospheres, in the last few years!