Itelmen and Chukchi are two Paleo-Siberian languages spoken in the northeastern corner of Russia, at the far end of Eurasia. They are related to one another in the small Chukotko-Kamchatkan family.

The Itelmen are considered to be the original inhabitants of the Kamchatka Peninsula when the first Russian explorers first arrived. The Itelmen then numbered in the tens of thousands and spoke three distinct dialects. Following these first forays, use of Itelmen quickly began to wane. Assimilation occurred due to the introduction of Christianity, harassment by Cossacks, and diseases like smallpox coupled with an influx of Russian settlers, causing Itelmen language use to wither, two dialects (Southern and Eastern) to disappear, and Russian to expand. By the beginning of the 20th century, most Itelmen had Russian names, and only 58% spoke Itelmen. By the 21st century, census records indicated 3,180 ethnic Itelmen, with only 385 speakers of the language, and perhaps only 40 using it fluently (Pereltsvaig 2014, “How to Save the Itelmen Language”). All fluent speakers were above the age of 50 at this point, and virtually all Itelmen knew Russian.

Many other groups have similar histories, in which assimilation occurred gradually and Russian becomes more useful and consequently more used among an ethnic group. In some cases, assimilation is forced, as when Cossacks demanded loyalty to the tsar in Imperial times, or when the communists brought collectivization. But often the process was simply a matter of Russian culture, money and power gradually permeating the Siberian forests and tundra. As more and more Russians move in, they bring government, media, jobs, and education, and young Siberians have more reason to learn Russian and less reason to learn their mother tongue. Siberians who abandon traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyles learn Russian for convenience and necessity.

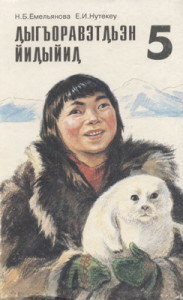

Like the Itelmen, the Chukchi subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and herding, live in the cold northeast near the Kamchatka Peninsula, and encountered Russians in the 17th century. However, unlike the Itelmen, there were an estimated 15,107 Chukchi by 1989, of which 10,636 considered Chukchi their native language (Burykin 2005). Chukchi is commonly used within families (mostly by older men) and in work activities like hunting brigades and small clothing workshops. A Cyrllic-based alphabet supplanted the little-used Latin alphabet in 1937 and subsequently saw use in schools, newspapers, literature, and eventually education, and during Soviet times TV and radio broadcasts in Chukchi were introduced.

Though Chukchi is not moribund like Itelmen, it faces its own set of challenges. Though it is taught in schools and found in textbooks, Russian is still the dominant language in education. Chukchi is more widely spoken by the older generation, and from 1959 to 1989 the percentage of Chukchi who used the language as an L1 fell from 94% to 71% (Burykin 2005). The situation of the Chukchi is similar to that faced by other languages whose speakers number in the thousands, whose existence is not so immediately threatened but whose culture and future are nevertheless at risk.