By Jacqui Reid-Walsh and Colette Slagle

This metamorphosis book is important in the development of the strip format to a booklet format since the 1814 edition is the earliest known publication that includes a note to the child reader. The notes shows a concern for the potentially terrifying movable images and dire words on the readers’ psyches.

1814 version with mending tape. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections) For larger view see image gallery page of website.

1814 version with mending tape. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections) For larger view see image gallery page of website.

Unfortunately, one line of the note is largely obscured with what appears to be mending tape, an intervention that was presumably performed by an earlier collector. Fortunately, special collections also owns an 1817 edition also published by Rakestraw. It has the same cover and the same order and numbering of verses. Since it is in better condition we can easily read the full text of the note:

“That we may not mislead our lit-

tle readers, it is desired they would

understand the Mermaid and Grif-

fin to be only creatures of fable, that

never did exist. And although Death

is represented in the form of a hu-

man skeleton, yet this is only an

emblem ; for Death is not a being,

but a state.”

1817 clean version of note to reader. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections)

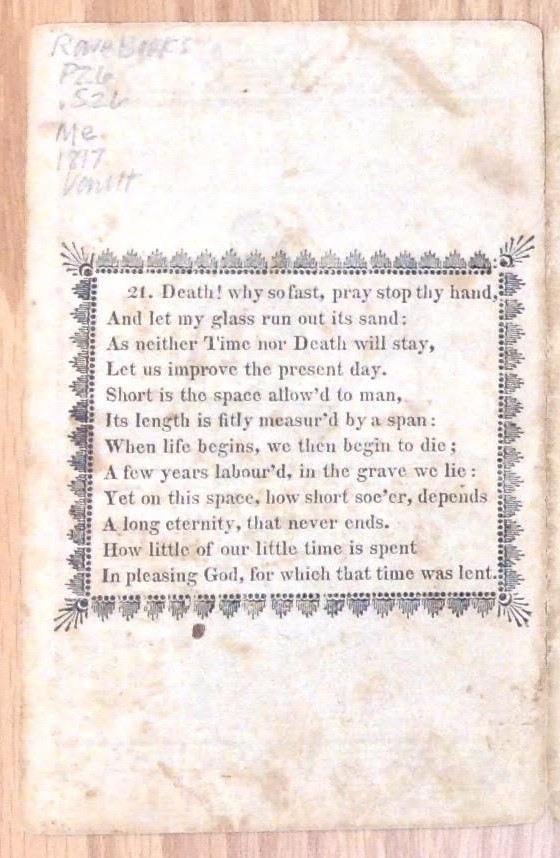

In addition, we noticed discrepancies between the two versions that take us back to all four versions transcribed so far (1810, 1811 {in the Bodleian), 1814 and 1817). The most obvious change in the 1817 version is the spacing in the final set of verses (no. 21) that unusually are presented as one stanza. In the three earlier versions no. 21 is split into three stanzas. Furthermore, the final punctuation mark has changed slightly among the versions. In 1810 the verses end with a question mark, in 1811 the final punctuation is an exclamation point. In 1814 and 1817 a period is used. The different punctuation marks change how the sentence is read and casts a different inflection on the final message. The lines read: “How little of our little time is spent/ In pleasing God, for which that time was lent” Reading aloud together we could hear how the moral changes considerably with different punctuation. We move from a question that demands an answer, to emotional affect, to neutral observation.

1810 version last set of verses ending with question mark. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections)

1811 version last set of verses ending with an exclamation point. (Photo courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, Vet. K6 f.92)

1817 version with one stanza instead of three, and the verses ending with a period. (Photo courtesy of Penn State Libraries, Special Collections)