Jacqueline Reid-Walsh

My interest in interactive books, especially of those for babies or very small children is of quite recent standing as I have begun to explore more of the publications by Dean and Son. The company started producing rag books at the turn of the 20th century with the stated aim of creating safe and durable books for very young children. Although the rag books were not reprints, they are a good instance of the same educational genres as the paper books, here a picture-book primer (Cope and Cope, 11, 13). As with all primers, the aim is to educate caregivers and babies about their immediate surroundings and to do in a safe non-threatening way (Nodelman and Reimer, 130). What sets the Dean rag books apart from a paper primer is that the safe environment is not restricted to the images or words but also in their materiality. The soft, pliable material exudes its own atmosphere– a cozy domesticity apart from any content (see Reid-Walsh and Rouse, in press).

Previously I have approached Dean and son’s output as being one of the founding families of movable book design in England in 1856, the other main family being Darton and son (McGrath, 16). Because of their association with 19th chapbooks for children, part of the “cheap print” phenomenon, their implied audience includes a broad economic range of readers. I now realize that their innovations in design include innovations in materials, and that their rivalry with Darton extends to both aspects.

With rag books I have worked mainly with images and one pristine copy of What is this? What is That? (circa 1905) held in special collections at The Pennsylvania State University Library. In May I had the opportunity visit the Baldwin library at the university of Florida and examine more rag books largely by Dean. I also became acquainted with others published by their main rivals the Darton family and the McLoughlin Brothers in the US.

In some cases, the choice of substrate for publishing seems to be arbitrary — for instance story books that were published on both paper and rag or those that combined a paper surface with a fabric backing. Here I wondered who the implied readers were : the texts such as fairy tales are directed towards a more generic child audience while the rag ones towards babies and toddlers.

One of the notable features of the Baldwin collection is how the founding curator bought books both in pristine and used conditions. With the rag books this included books that had been washed so can be compared to the pristine versions. Here I show images of a few little-used and well-used rag books, including one I have seen in different editions at both Penn state and the Baldwin. Throughout I discuss the Dean rag book claim in their logo of “quite indestructible” in terms of the implications of the qualifier. On the one hand, it could be understood as (British) understatement, or/and descriptive evaluation (Reid-Walsh and Rouse, in press). The descriptor may also allude to earlier handmade paper-making strategies up through the 18th century when paper was composed of rags and thereby more durable in comparison to machine-made pulp paper.

In terms of the claim of indestructability and others such as safety and hygiene, first I show images of the same books in different states. Then I engage in a brief comparison of two editions of What is this? What is that? (circa 1905 and 1925?).

The same book in two states: When I grow up (Baldwin library circa 1910)

This book evokes an affluent pre-world war one world with fashionably dressed woman and children, formal chauffeur and glamourous car. The handwritten style text next to the young boy provides a subtitle as well as his wish “I’ll be a Motor driver.” The rag material is firm and the pinking clean. With the washed book the material has softened, and colors have faded and changed — the green turning-blue gray, the blue washing out almost completely, the print text has disappeared, but the red is still quite vivid. The sewing and pinking are starting to fray. With some of the other more used books, the pinking has completely worn away. This shows that “quite” “indestructible” is perhaps a fair assessment.

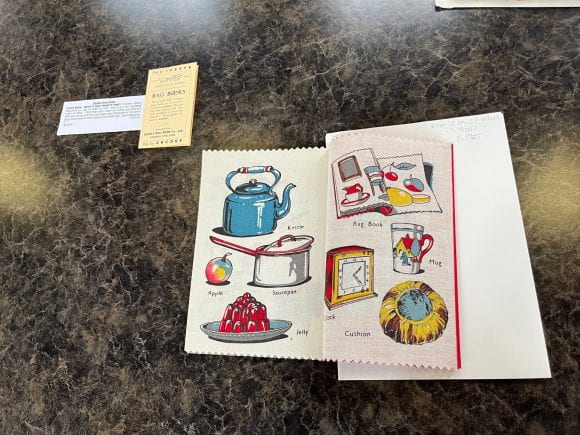

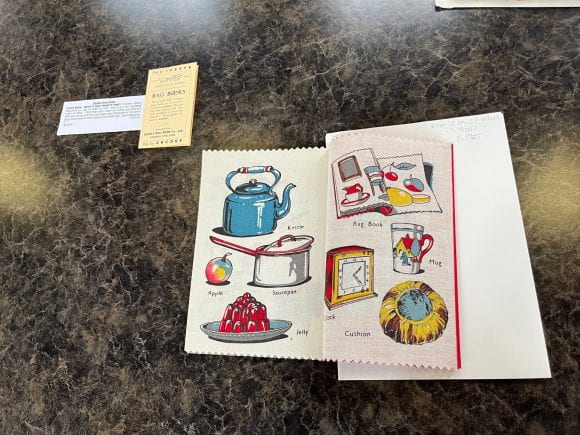

Two versions of What is this? What is that? (Penn State 1906, Baldwin 1925?)

These two editions effectively evoke different period representations of early childhood in terms of their household and play objects. In both cases, the only images of humans appear on the front covers.

The 1906 edition creates a bucolic image of lower middle and middle class early childhood. It includes depictions of a number of multiuse and household objects. Notably the cover depicts a small wheel barrow being used by a toddler (presumably a girl?) in full Victorian nursery attire. In the barrow are non-gender specific toys such as a lamb on a pull board, and ball. This continues within the book.

In comparison, the 1925 edition book updates the child representation and objects to evoke a “modern” and more affluent household. The images include more toys and emphasizes gender specificity in clothing and objects. The front cover does this strikingly — the girl with fashionably bobbed hair and boy are well dressed. They have an elaborate doll house and several toys like dolls and a stuffed bear. Notable is the racist golliwog.

It is interesting to note that one page includes a self-referential image of “rag book” which closely recalls and perhaps reworks images from the earlier edition. The image is set amongst household items and sweet treats. The image of the alarm clock on the page, as with the image of the motor car on the front cover or the other rag book, indicates an easy way to date a book (apart from fashion)!

References:

Cope, P. and D. (2009) Dean’s Rag Books & Rag Dolls. New Cavendish Books.

McGrath, L. (2002) This Magical Book. Movable Books for Children, 1771–2001. Coach House.

Nodelman, P and Reimer, M. (2002) The Pleasures of Children’s Literature. Pearson.

Reid-Walsh, J. and Rouse, D. (in press) “Understanding the Design Values of Baby Books: Materiality, Co-Presence and Remediation,” Children’s Literature in Education: An International Quarterly.