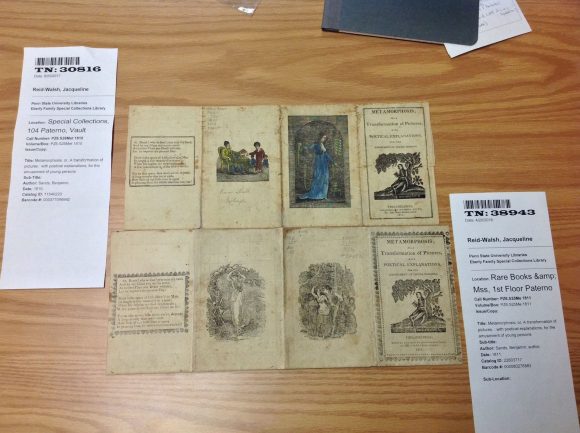

Last week I presented at a conference hosted by the East-Central Chapter of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies in Gettysburg. The town and especially the college are exquisite. The conference theme was “Crossroads and Divergences” and my paper was part of a focused panel called “Folds and Formats: Fitting Knowledge to the Page.” The moderator and organizer was Bénédicte Miyamoto who is an Associate Professor at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3. The other presenters were Dr. Faith Acker, a research fellow at the Folger Library, who presented a fascinating paper entitled “Shaping Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Folds, Formatting and Paratexts from 1599 to 1790” and Professor Eleanor Shevlin from West Chester University who presented a provocative paper called “ A Matter of Formats: Genre Interplay and Remaking Marketplace Attitudes.” My paper examined the folds and flaps in both the strip format of the 17th century British The Beginning, Progress and End of Man, and the booklet format of the 19th century Metamorphosis, or a transformation of pictures. My aim was to contribute to the panel theme about folds and formats in terms of two questions in particular. They were, “Were content and format closely intertwined?” and “How did printers, engravers, or book sellers experiment with new forms and folds of publication with what results.” ?

In the 20 minutes allotted I did not progress much beyond showing images, sharing the questions, and handing out facsimiles for the audience to play with and perhaps speculate with. I shared that my answer to the two conference questions was a resounding yes. Regarding the first question, the format I argue makes or enables different kinds of content, the images and verses, to appear in different orders as they are manipulated by the reader -viewer-player or interactor. Regarding the second question, in respect to the strip format, the printers used the wood blocks in unusual ways by placing them under the flaps or over the joins made by the closed flaps. (See https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/theconveyor/2017/02/06/transformations-in-print/1-adam_trans/

and

https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/theconveyor/2017/02/06/transformations-in-print/3-mermaid_trans/)

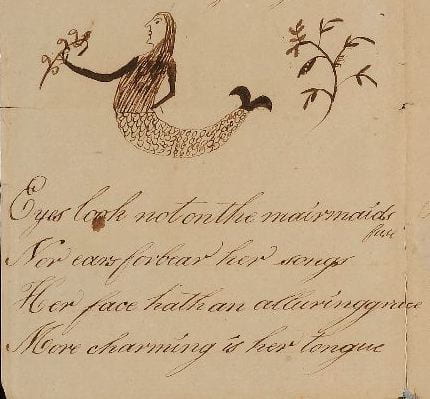

In the discussion after the facsimiles were distributed, one participant, a co-presenter, was intrigued by how the inner images under the flaps form a secret or private space that is only revealed when the flaps are lifted (Shevlin remarks, Oct 26, 2019). This perceptive insight draws attention to what images are not immediately apparent but hidden beneath the flaps. The mermaid, eagle with child, heart as money bag and skeleton only appear when the double transformation has occurred by lifting both flaps. Is there a quality that draws them together in this secret space? Or, since the double transformation is achieved in different ways in each panel: in the first two panels this is achieved by turning the top flap up and the lower flap down, while in the last two panels the flaps are usually turned in reverse order, does the pattern of revealing serve different functions? Moreover, in all seen versions, whether 4 or 5 panels in the printed versions and perhaps even more in the homemade texts, the order of these key images remains the same.

Looking at the first and last images for example further questions arise. With the first panel, could the hidden mermaid be a lure for the implied male viewer? (the verses suggest so). Yet, the mythic mermaid by her positioning under Adam/ Eve has a hidden connection with Eve. On the one hand, Eve is created by lifting the top flap of Adam’s torso–perhaps enacting as it were the biblical origin story. On the other hand, by the mermaid’s placement under both biblical figures she may suggest an alternate origin story for women. What would female viewers think?

(See https://sites.psu.edu/learningasplaying/2018/02/16/mermaid-at-the-centre/)

With the last panel, could the contrast between the richly garbed man and his naked skeleton be intended to be a moral shock as well as a conventional memento mori? The first and last images form stunning contrasts and unless the strip is refolded so they are juxtaposed sit at opposite ends of the text.

For their part, the two middle hidden images seem to serve a linking narrative function to me. The eagle with baby and the young man’s heart that chases gold are linked to the final image of the rich man/ skeleton tying these three episodes together. Child, youth, age and death –the stages of man.

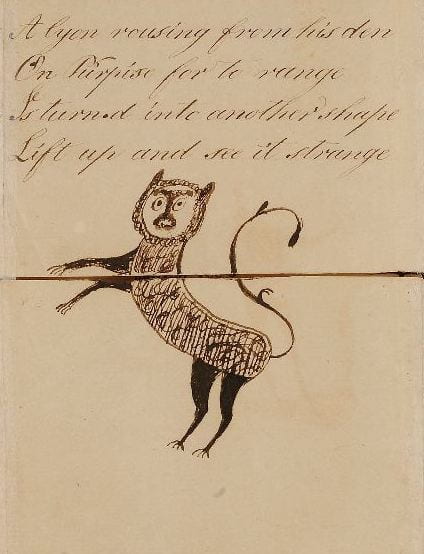

I have been discussing the images when the flaps are lifted in the intended order following the instructions. When we disobey the directions and turn contrarywise, we discover incongruities not referred to in the verse, like the merman and a monster made of the lion and eagle in the opposite manner to the Griffin. Yet due to the design and way the text and images are formed, no matter a reader-viewer-player’s patterns of engagement, the inner, hidden images remain