“What is a child?” and self-constitution

Tamar Schapiro‘s “What is a child?” (Ethics, 1999; the earliest paper listed on her CV) aims to solve several problems about the nature of children as seen from the Kantian perspective. Key among these problems is the way a child becomes an adult: how she goes from not-an-agent (and thus suitable for moderated paternalism) to an agent. Children rely on adults in several ways: as models for autonomous decision-making, as exemplars of styles of life to try on, as sources of discipline (an external conscience) and thus the feeling of responsibility. Adults can even suggest specific or broad reasons for action that the child should adopt. But adults cannot simply make the child autonomous; they cannot constitute her as an agent. This is because agency involves acting on the basis of principles to which the agent has committed herself. Committing oneself to principles, and acting on the basis of them, seem not to be forcible.

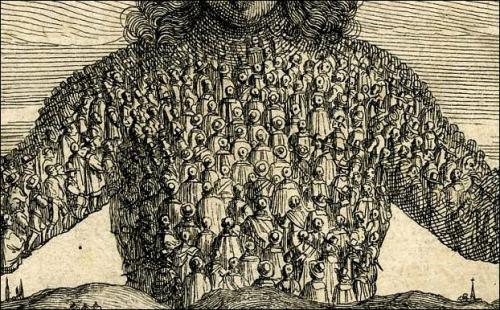

The consequence of this observation is that the only efficacious constitution is self-constitution. But self-constitution looks paradoxical, if the self to be constituted is one that can choose freely (i.e., on the basis of its own reasons), and yet the constitution (i.e., selection of principles, acting on principles) itself must be freely chosen. Schapiro presents the paradox from the perspective of political organization:

Prepolitical society has to pull itself together, but there is no one—no unified social body—there to do the pulling. Thus it is hard to see how the transition from the state of nature to the civil condition is even conceivable. It is not conceivable as an act because there is no agent to undertake it. But neither is it conceivable as a blind process because its result is a new normative order. (731) [I quote her further discussion of Kant below.]

Schapiro aims to explain the possibility of self-constitution. Her ideas are expansion and play. Children start with a limited scope of sovereign discretion: actions about which they can freely choose. By allow them to use this discretion, not only do they gain practice in exercising choice (J.S. Mill prizes this practice); they try out rules of judgment and acting on the basis of principles that could apply beyond their as-yet-limited scope. This gives them starting points for making decisions in wider areas; and as parents recognize that children could act autonomously in new areas, they give them the (external) liberty to do so. We may see an analogy Kant: enlightened people can constitute themselves into a small republic; the rules of self-government they create for themselves would apply just as well to a somewhat larger republic; those laws, undergone whatever modification they receive, would apply just as well to a yet-again-larger republic.

Children also adopt personae with bolder and more integrated principles for action that they themselves possess, and playfully/imaginatively/hypothetically act on the basis of those principles. This gives children experience with the feeling of the responsibility and freedom associated with such adoptions, or they see whether they like any particular sets of principles. This presumably helps them (i) make the leap to committing themselves to some set of their own principles, and (ii) decide which set of principles to make their own.

I want to mention here only two ways in which this account does not “solve” the paradox of self-constitution (though it does seem to explain, in an important way, how children do in fact becomes agents).

1. Schapiro provides the child with a minimum of autonomy; the child’s task is only to expand it. This means that the child in the argument is already “being addressed by her motivational impulses”; she sees them as making claims on her that she must adjudicate by appeal to some principle that is her own. Schapiro takes it as a matter of “developmental psychology” that as infants graduate to childhood they simply acquire this capacity (735n1).

2. Schapiro notes that the notion of play does not eliminate the paradox. For the motivation to play is either mechanical, passive, spontaneous, in which case it seems not to produce a feeling of autonomy, or it is freely chosen, in which case it depends on that which is means to explain (732n37).

Here are Schapiro’s remarks on Kant on the paradox of self-constitution:

It is probably appropriate, then, that in the political case, Kant oscillates between describing the transition from the state of nature as an act (of joint agreement to a social contract) and as a process (the effect of unilateral coercion, by individuals and by a providential nature).

For the purposes of attributing full moral status to a state or a person, Kant believes it is necessary to conceive of the unifying transition as an original act outside of time. He writes,‘‘The act by which a people forms itself into a state is the original contract. Properly speaking, the original contract is only the idea of this act, in terms of which alone we can think of the legitimacy of a state’’ (DR 6: 315). Similarly Kant holds that our attributions of responsibility to individuals seem to presuppose that individuals freely adopt their characters in an act of original choice: ‘‘To look for the temporal origin of free actions as free (as though they were natural effects) is therefore a contradiction; and hence also a contradiction to look for the temporal origin of the moral constitution of the human being, so far as this constitution is considered as contingent, for constitution here means the ground of the exercise of freedom which (just like the determining ground of the free power of choice in general) must be sought in the representations of reason alone’’ (RWR 6: 39 – 40; see also CPrR 5: 99–100, where Kant discusses ‘‘born villains’’). And yet when Kant tries to describe the transition prospectively and without regard to our practices of attributing responsibility, he suggests that the social contract is an agreement which individuals can be forced to enter. For he asserts that in the state of nature, every subject must ‘‘be permitted to constrain everyone else with whom he comes into conflict about whether an external object is his or another’s to enter along with him into a civil constitution’’ (DR 6: 256). And in the political writings, Kant speaks of nature or providence as an invisible force which ‘‘guarantees’’ the establishment of the civil condition by compelling us to enter into it, ‘‘whether we will it or not’’ (PP 8: 365). See also Kant, ‘‘Conjectural Beginning of Human History,’’ pp. 66 – 67. (733 and n36)