I’m sure most of you have had to deal with being able to remember the lyrics to a song you haven’t listened to for five years, but as soon as you have to memorize some flashcards for an exam you’re mind goes blank. Why is that? Why can’t my brain just memorize what I want it to memorize?!

One reason as to why when you are studying you cannot seem to remember anything is because the amount of stress you are feeling. There is actually a principle that was named after two scientists, Yerkes and Dodson, stating just that. The two performed a randomized control trial on a set of mice to see how long it took them to learn to travel down a white pathway as opposed to a black one. The independent variable in this scenario is the intensity of the electric shocks given if they travel down the black pathway, and the dependent variable is the amount of time it takes to avoid the black pathway. The scientists came to see that a stronger shock would cause the mice to move faster away from the passage they were intended to avoid, and a smaller shock would take longer for the mice to learn to avoid it. I think that most people can agree that this scenario would make sense seeing as I would also try to avoid being electrically shocked.

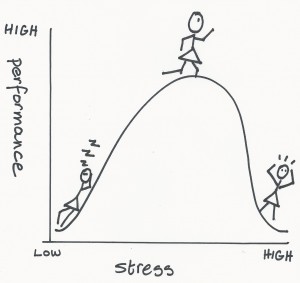

However, as other scientists began to perform meta analysis on Yerkes’ and Dodson’s work, they came to realize that there is more than just the two outcomes of performance. With too little motivation (ex. a test really far away), you have little incentive to act, therefore your performance is also at a low level. As the test moves closer, you have a higher incentive to act, and your performance level is also high because stress has not conquered your ability to study effectively. And lastly, when it is an hour before the exam, you have lots of motivation to study, but your performance is shot because your stress levels are off the charts.

The image above depicts the three separate scenarios. Originally, the hypotheses that had existed explained that arousal and performance were positively correlated, forming a positively sloped line.

The field of arousal and performance does not suffer from the file drawer problem, in fact, there have been many experiments completed and documented. Another example is a study done by Broadhurst in 1957. His population for his randomized control trial was rats as opposed to mice, and his motivation tactic was oxygen level. His experiment concluded a curving correlation between arousal and ability to function as well.

However, scientists are unable to say that there is a direct causal relationship between stress and productivity. Backs, who in 2001 evaluated the signs of a heavy workload by measuring individuals’ heart rates and breathing rates, believes that he found a causal relationship between the two components. However, he explains that many scientists use physical measurements to make causal conclusions about the mental health of a person or population. He warns that the assumption used in this technique should not be trusted because within a relationship that seems obvious, there could be many hidden causes that the scientists are unable to identify, also known as confounding variables.

Overall, it is evident that it is better to start studying early before the exam in order to keep productivity high and stress levels low. Not only will it help you score better, but may be beneficial to your physical health in keeping the levels of your cardiac and respiratory system balanced.

Source: Staal, Mark A. “Stress, Cognition, and Human Performance: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework.” (n.d.): n. pag. Nasa. Nasa, Aug. 2004. Web. 21 Nov. 2016.

Your research of why cramming is so detrimental to students’ studying made me wonder why we as students continue to do it despite constant reminders not to procrastinate. I like how you explained that with further away deadlines, students’ incentives to study are lower than with closer deadlines. In my Economics class we learned not only about incentives but also about opportunity cost and tradeoffs, which in this case means that students will study for what they are getting the best value out of, while giving up the next best alternative. For example, if a student has an exam tomorrow, they’ll study for that, but the opportunity cost is that they put off studying for the test they have the next week. Many students fall into this cycle, leading to more and more cramming.

On another note, I wondered if what you said about stress levels negatively effecting studying is true only for tests, or if it applies to other assignments as well. You also mentioned that scientists did not find a correlation between stress and productivity, which I think might be because it depends on the assignment, and like you mentioned, the amount of stress there is on the student. I find that when I’m in a high stress situation, I am much more focused on my projects or essays because I subconsciously know I don’t have time for distractions, whereas studying for an exam while in a high stress situation does not help me at all. This is similar to what you mentioned about our incentive to study being higher without being stressed, once the test moves closer.

Dear Anna,

This article has a ton of comments on it because, literally, everyone can relate to it. You do not even realize how many times I have gone into some state of depression because I crammed the night before and did horribly on the exam! Great choice of an article topic.

In addition, the graph you posted in you blog about the stress levels and the high performance seems to be exactly right, from what I have experienced! When I have adequately prepared for an exam, I seem to have moderate levels of stress because I know I won’t do horrible, but there is still a possibility I won’t do the best. What is the result? A very high test grade! However, whenever I find myself either with very low stress (almost never) or with too much (happens often), I happen to do poorly! This is exactly why studying is essential to doing well. Thus, there is most likely a direct correlation between stress and performance in school.

Stress is sometimes necessary and essential for many facets of life, especially considering that you just proved it is somewhat helpful in school. Are you curious as to what else it is beneficial for? Find out with this awesome article:

http://inspiyr.com/benefits-of-stress/

I certainly relate to this blog. In high school, I could study the night before, the morning of and immediately before a test and do very well. Maybe it was that the subject matter wasn’t that vast or that I found the topics to be easier, but I received excellent grades and formed bad habits. Now, as I work my way through the first semester of freshman year in college, I realize that cramming is not the way to survive, to do well or to retain information. I relate to your comments about stress and the inability to remember what you are studying when time is running out. I also agree with your reference to lack of motivation when there seems to be a lot of time to act.

I found an article written by Tom Stafford, Memory: Why cramming for tests often fails, he refers to a study that reported that cramming was less effective than spacing out learning for 90% of participants in an experiment. However, the perception of 72% of those participants thought it was more beneficial to cram for an exam. Stafford’s article points out that familiarity with material is not memory and that many people confuse the two. He goes on to describe the different parts of the brain that support memory comparing sensory or visual memory versus true recall of information. I find this topic fascinating and could go on about it but I need to get the frontal cortex and temporal lobe areas of my brain focused on some subject matter for a test next Wednesday.

Here is a link to the article written by Tom Stafford, check it out: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20140917-the-worst-way-to-learn

Very good topic! As a transfer student, I’ve had a hard time adjusting to Penn State’s reliance on exams that are worth between 20-30% of your grade each time. Therefore, I feel a huge amount of stress leading up to exams, as I’ve never been great at taking tests (which is what everyone says, I know). Therefore, my grades isn’t as high as I would like, making my stress higher. I think my problem is cramming, but that’s always the way I’ve done things. Therefore, it’s hard to break the habit and change my entire studying style. However, science has proved time and time again that we need to stop this strategy. For the end of the semester, I aim to switch up my studying strategy. I hope it helps!

Overall there is nothing good about cramming and we all know that even though many of us continue to do it. I think many people learn differently making their study patterns difficult to compare to others. Especially because there are so many confounding variables affecting a students study habits like learning disabilities, ADD, and difficulty of classes. For example, me and my roommate are both in the same Econ class, I will start studying weeks in advance for a much longer time and she will study a little the night before and we still get similar grades. So for the most part I think when and how someone studies completely depends on the person.