I teach Lysenko as an example of what happens when science isn’t allowed to work properly because outside political influences intervene. That’s a very extreme case (skeptical Soviet scientists got imprisoned and killed) but for several years I’ve been using Prof Mike Mann in our very own meteorology department as an example of how politics in this country can also try to make science work differently (for the most part, so far without success). For producing the iconic Hockey Stick graph, Mike has been on the receiving end of death threats, email subpoenas and fraud investigations (detailed here). As he put it, the rules of engagement you learn as a scientist [robust debate] are not the rules of engagement used against you as a scientist [personal attack]. This year, finally, his schedule and the SC200 time slot lined up to make it possible for him to come to talk in class.

Mike Mann in action Oct 25

It was an interesting experience for me (and I hope the students). The comment wall was more active than I have ever seen it. Questions ranged across the political spectrum and varied widely, some focusing on the science of climate changes (what’s the evidence?) and others on the politics (e.g. “The Democratic Liberal agenda of this presentation makes me sick.”). I had trouble trying to sift through all the comments to find a balanced range of them to put to Mike. For the first time, I wondered if the class is actually too big – so many views and interests, most of which might not have been dealt with sufficiently in so brief a time.

After, I asked Mike to comment on some of the questions we didn’t get to. Below, the questions (bold) and his answers where he offered them.

Is the carbon footprint of building devices such as solar panels and putting expensive filters on car exhausts worth it because of the building process?

What’s our preferred method of alternative “clean” energy?

What are your thoughts on the youtube video ? [Hide the Decline]

Where is the decline?

Alas, it is largely in the quality of the public discourse over matters of policy-relevant science.

Did you sue everyone for the videos they made about you?

Does that mean a democrat would deny climate change if from Oklahoma?!

In my view, it shouldn’t mean that *any* politician deny climate change. But unfortunately, most climate change deniers these days are on the republican side of the isle, and it’s not a coincidence. Folks like the Koch Brothers have spent millions of dollars funding primary challengers against republicans who express an enlightened view on climate change (like former republican congressman Bob Inglis of South Carolina), i.e. they have sought to “purify” the republican party with respect to climate change denialism. And that’s a big part of how we’ve arrived at the extreme partisan polarization we now have on climate change. It is ironic, since many past Republican presidents (Nixon, Reagan, George H W Bush) displayed leadership in acting on climate environmental problems like acid rain and ozone depletion. It is only relatively recently that the environment has become a partisan political issue. And it is most unfortunate. I talk about this in my new book “The Madhouse Effect”.

In 2014 there was record sea ice in Antarctica.

If we do eventually manage to stop our growing carbon footprint, is there any way to bring it back down to safer levels?

Is it too late to do something about climate change?

If you could have us take away one point from today, what would it be?

Has all these government issues made you even more passionate about climate change?

What can be done to separate science and politics?

What’s the effect of rising sea levels on the subways in NYC? Isn’t there something about brine levels?

Why is climate change so heavily denied by a majority of republicans?

Addressed in a separate response above.

What is a non-believers thought process towards climate change?

How does one combat this issue of climate change when the United States and many other countries are so dependent on fossil fuels? Is there an alternative?

What company does Frank Luntz work for? Why did he want to confuse the public?

Luntz is a pollster, and has largely worked for republican clients. It is unclear what his own views are. He is merely doing what is asked by his clients, and I doubt he actually

wants to confuse anyone. But in the end, his polling and focus group research has indeed provided fodder for those looking to confuse the public.

Why do you think people are so avid on denying climate change?

Have you ever been successful convincing someone that climate change exists?

I like to think so. I’ve given many public lectures and media interviews over the past decade and a half, and I’d like to think that my fact-based approach to talking about climate change has won over many honest skeptics. And indeed, I’ve been told a number of times by people that had been skeptical beforehand that they were convinced after listening to what I had to say. That having been said, there is a fringe sector of the population that sees issues like climate change entirely through a partisan political lens, who see it as a part of their tribal political identity. For those people, facts and figures and information and logic alone are often insufficient to change their mind. Their mind is already made up. And our efforts, arguably, are better spent on the “confused middle”—a large group of people in the political center who *think* that there is a scientific debate about whether climate change is real. They are typically receptive to learning more about what the science has to say.

What do you see the future looking like ? How much hope do you have for our generation (us students)?

I am optimistic for several reasons. In “The Madhouse Effect”, we spend the last chapter of the book outlining the reasons for cautions optimism in the battle to combat climate change.

I’m optimistic because of the tremendous progress that has been made, domestically and internationally, over the past few years in tackling climate change—the huge growth in renewable energy, the monumental agreement last December in Paris to lower carbon emissions that was reached by nearly 200 nations around the world (read e.g. this Huffington Post commentary I wrote about the Paris agreement), the fact that global carbon emissions dropped for the first time in decades last year even though the global economy continued to grow). I am also optimistic because millennials (read—you folks!) have really gotten it in a way that older generations have—there is considerable energy and passion surrounding the issue of climate change specifically, and environmental sustainability more generally, among college students today. I see that here at Penn State, and at other colleges and universities around the country where I lecture. I think that energy and passion will help power the critical transition that is underway toward a green energy future.

******

But most amazing to me was that Mike really got the classes attention when he was asked about whether its good or bad to have celebrities weighing in on the debate. All was normal until he said Leo. Leo, more than glaciers melting, NY flooding, extreme weather events, …… Leo got a reaction. LEO? I did not know whether to laugh or cry. At least its not my generation who will be mopping up the mess.

Anyway, Mike was worried after that the class did not believe he advised Leo. So here folks, is Leo and Mike (with more here, including Bill Clinton):

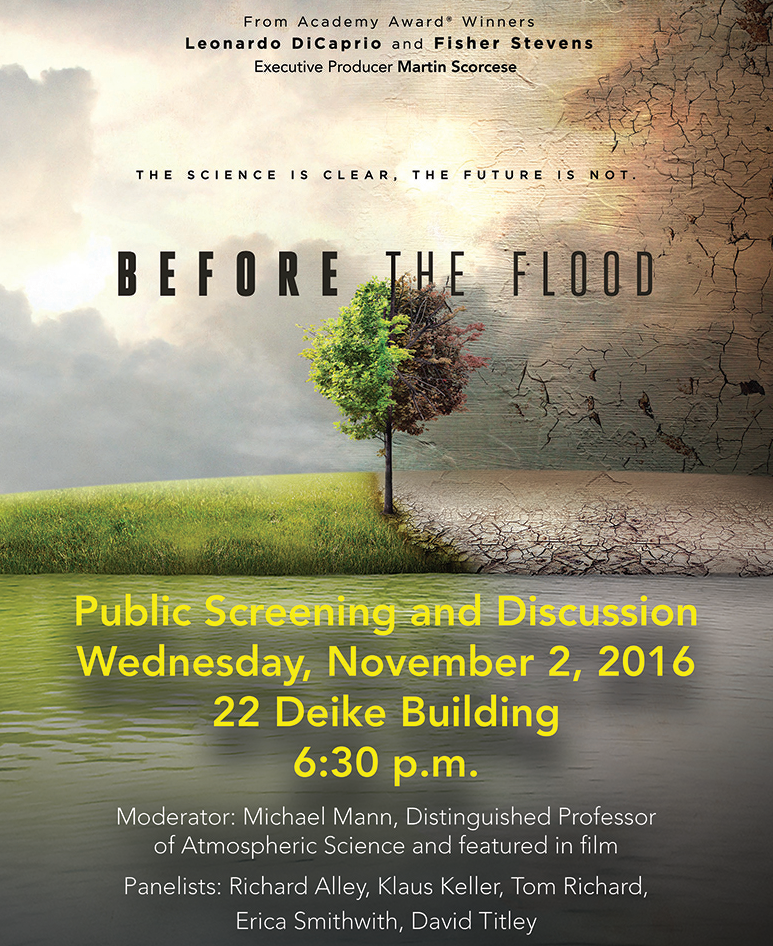

And here’s the Penn State premier of the film Mike helped Leo make:

Mike is very keen any interested students come to that event. And that students who liked — or did not like — what he said follow him on Twitter @MichaelEMann.

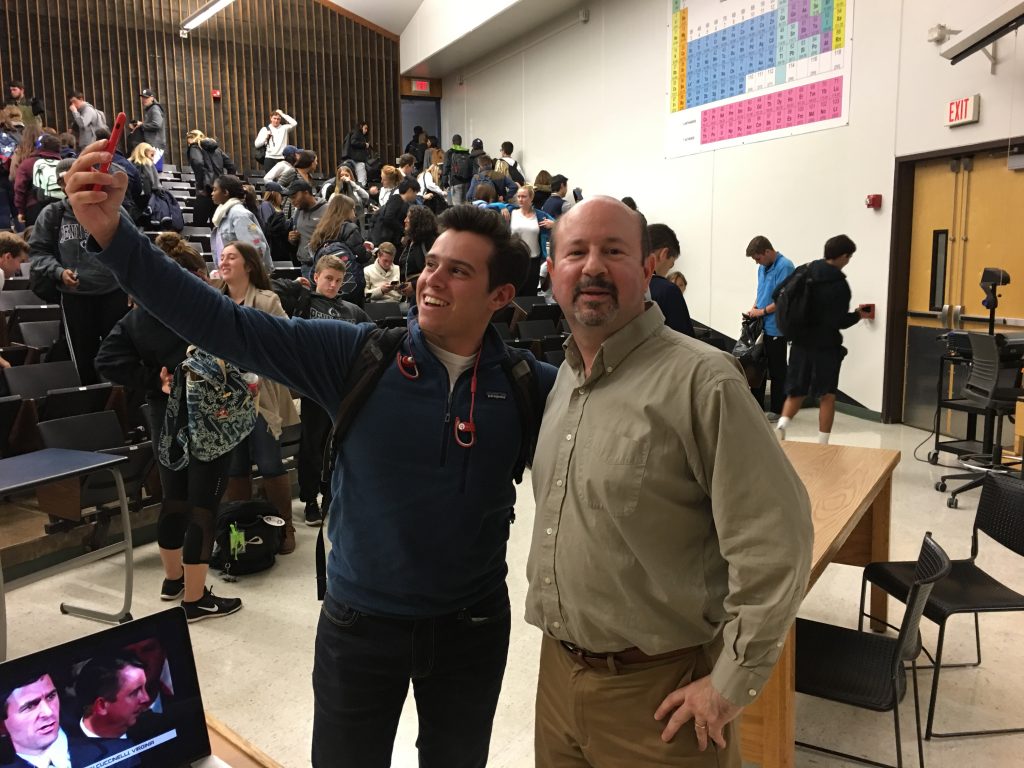

And, a final irony, Mike himself is now apparently something of a celebrity. Here’s the selfie shot after class.

The work of climate scientists like Mike and his many colleagues here at Penn State repeatedly survives peer review. That means the science as sound as it can be at this point in time. My overwhelming impression is that all of the scientist involved are very scared about what they are concluding. Many of them are knocking themselves out trying to warn the public. I wish the SC200 class of 2016 — and their children –the very best as a they struggle to deal with the fall out of the current US political inertia.