Matt Kenney is a professional woodworker and editor at Fine Woodworking Magazine, writing frequently about tools, techniques, and box making.  His education is in philosophy, and I wondered how that affects his woodworking. In answer, it doesn’t directly: “Philosophy doesn’t necessarily influence my woodworking, but because of my background in philosophy I am better able to understand why woodworking is so important to me. I am better able to appreciate why craft is a valuable human endeavor.” He is able to convey these thoughts very well in writing as well. Despite not proofreading his responses to my questions, he wrote quite eloquently about his journey as a woodworker and his philosophy and process. Matt’s full responses are at the bottom of the post.

His education is in philosophy, and I wondered how that affects his woodworking. In answer, it doesn’t directly: “Philosophy doesn’t necessarily influence my woodworking, but because of my background in philosophy I am better able to understand why woodworking is so important to me. I am better able to appreciate why craft is a valuable human endeavor.” He is able to convey these thoughts very well in writing as well. Despite not proofreading his responses to my questions, he wrote quite eloquently about his journey as a woodworker and his philosophy and process. Matt’s full responses are at the bottom of the post.

Becoming a Woodworker

Kenney started working with wood as a kid, taking inspiration from his father, a contractor, and building things such as “tree forts, skateboard ramps, and probably a bunch of things too dangerous to admit.”  He survived to graduate high school and went on to study philosophy in college and graduate school. In the course of pursuing his doctorate, he married and started to build a few projects for his home, including a gardening tool box and crib with basic tools. Once again, he was “hooked” on woodworking. At this point, Kenney had become a professor. By chance, the father of one of his students was a furniture maker. As the student put it, “My dad is a professional furniture maker but thinks he’s a philosopher,” and Kenney was the inverse. He went to meet and learn from that furniture maker, and a few years later went to work at Fine Woodworking as an editor. In each of these three stages of development as a woodworker, he was influenced by a different person who each played a very important role in helping Kenney to reach the level at which he works today.

He survived to graduate high school and went on to study philosophy in college and graduate school. In the course of pursuing his doctorate, he married and started to build a few projects for his home, including a gardening tool box and crib with basic tools. Once again, he was “hooked” on woodworking. At this point, Kenney had become a professor. By chance, the father of one of his students was a furniture maker. As the student put it, “My dad is a professional furniture maker but thinks he’s a philosopher,” and Kenney was the inverse. He went to meet and learn from that furniture maker, and a few years later went to work at Fine Woodworking as an editor. In each of these three stages of development as a woodworker, he was influenced by a different person who each played a very important role in helping Kenney to reach the level at which he works today.  In his younger years, his dad taught him to be interested in building things and to work with tools. As an adult, his student’s father showed him the fundamentals of building quality furniture. And now at Fine Woodworking, Mike Pekovich (see next week) is his design mentor.

In his younger years, his dad taught him to be interested in building things and to work with tools. As an adult, his student’s father showed him the fundamentals of building quality furniture. And now at Fine Woodworking, Mike Pekovich (see next week) is his design mentor.

On Style and Design

The style by which Kenney is most influenced is that of the Shakers, whose “mastery of proportion and color, and how they used doors and drawers to create beautiful arrangement of shapes in their furniture” is very appealing to him.  This influence is evident in most of his designs, but I asked Matt if he believes that he has developed his own style. “I think I have. My guess is that my boxes are fairly distinct from what others are doing. I strive to make boxes (and furniture) that are subtle and quietly beautiful. I focus on proportion and using the parts of a box to create a pattern. And I like using color (milk paint or fabric) to emphasize this pattern. But I don’t know. This is probably a question better answered by someone else, who can look at my work and compare it the work of others from the outside. It’s hard to see your own nose.” I have to say that I agree, he has developed his own style.

This influence is evident in most of his designs, but I asked Matt if he believes that he has developed his own style. “I think I have. My guess is that my boxes are fairly distinct from what others are doing. I strive to make boxes (and furniture) that are subtle and quietly beautiful. I focus on proportion and using the parts of a box to create a pattern. And I like using color (milk paint or fabric) to emphasize this pattern. But I don’t know. This is probably a question better answered by someone else, who can look at my work and compare it the work of others from the outside. It’s hard to see your own nose.” I have to say that I agree, he has developed his own style.

The descriptive phrase that comes to mind when I look at his work is “quietly sophisticated and playful.” Most of his pieces look rather simple: visually they are quiet, with lots of domestic straight grained wood.  The milk paint used sparingly in many of his pieces is part of what sets his style apart from that of the Shakers. The simple appearance of Kenney’s work conceals the skill and precision that he puts into building each piece, as well as his meticulous design process. He spends time iterating through a series of ever-more specific sketches and plans before working with the wood. He wants to be sure that there are no unforeseen difficulties as he builds a piece. Doing design this way makes it most likely that he will have a good result. He makes sure that beauty is the focus of his designs, but a piece can’t be beautiful unless it is also useful: “So, I strive to make useful beauty, beautiful utility. I want the utility and beauty of my furniture to dance effortlessly together.”

The milk paint used sparingly in many of his pieces is part of what sets his style apart from that of the Shakers. The simple appearance of Kenney’s work conceals the skill and precision that he puts into building each piece, as well as his meticulous design process. He spends time iterating through a series of ever-more specific sketches and plans before working with the wood. He wants to be sure that there are no unforeseen difficulties as he builds a piece. Doing design this way makes it most likely that he will have a good result. He makes sure that beauty is the focus of his designs, but a piece can’t be beautiful unless it is also useful: “So, I strive to make useful beauty, beautiful utility. I want the utility and beauty of my furniture to dance effortlessly together.”

Design is like any other skill in that it takes practice to become accomplished at it. For this reason, Kenney took on what he called the “52 Boxes Project,” setting out to build one new box each week for a year.  Over the course of the project he was not only reminded of the importance of practicing design but of other lessons on life and woodworking both: “simplicity is always better than complexity,” discipline is essential to success, and trusting a passion leads to good outcomes.

Over the course of the project he was not only reminded of the importance of practicing design but of other lessons on life and woodworking both: “simplicity is always better than complexity,” discipline is essential to success, and trusting a passion leads to good outcomes.

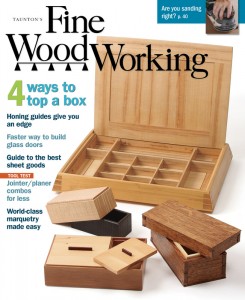

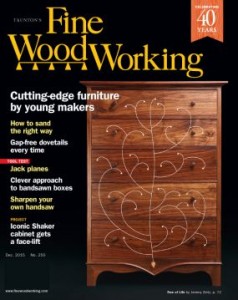

The cover story of one of the first issues of Fine Woodworking Magazine that I read was about making boxes without hinges, and it was written  by Kenney. He designed the box in the lower left of the cover. When I look back on that article in comparison to the very first boxes of the 52 Boxes Project (more than three years later), it is stunning to see the difference in Kenney’s style, initially rather generic, which further develops into something particularly distinct by the end of the year. Always technically sound and useful, his box making, in my opinion, is now genuinely beautiful.

by Kenney. He designed the box in the lower left of the cover. When I look back on that article in comparison to the very first boxes of the 52 Boxes Project (more than three years later), it is stunning to see the difference in Kenney’s style, initially rather generic, which further develops into something particularly distinct by the end of the year. Always technically sound and useful, his box making, in my opinion, is now genuinely beautiful.

In Closing, about Philosophy

I can’t say it better than this: “There is a voice inside each of us. Listen to yours. Discover what it has to say about beauty. Take this knowledge and use it to create furniture that you love. Let your passion for the craft guide you in the shop. And if someone gets in the way, tell them to go kiss a goat.”

�

Matt’s responses are posted in full below.

How did you get started in woodworking?

I’ve been making things from wood my entire life, and I owe this my dad. He was a contractor, so from an early age I saw that it’s possible to make something useful if you have some tools, some knowledge, and some wood. As a kid, I would help my dad with DIY home construction stuff around the house: making boardwalks (I grew up in Florida), a shed in the backyard, etc. With my brother and friends in the neighborhood, I built tree forts, skateboard ramps, and probably a bunch of things too dangerous to admit. Fast forward to my second year of marriage. I was two years into a Ph. D. program, and my wife and I were living a frugal life. She liked to garden, and I decided to make here a box to keep her gardening tools and supplies in. I had no idea how to do it, but I bought a few chisels, a toolbox saw, a coping saw, and some 1×12 pine. I worked away in the attic above our duplex and managed to get the box done. I was hooked. I made some more small things, still not knowing anything about furniture making, and getting tools. I started to read books on woodworking and searching the internet (back in 2000, there was far less than what’s available today). After several years and a few larger pieces, I undertook my most ambitious piece: a crib for my soon-to-be-born daughter. I made it on a small balcony, with a router, a benchtop tablesaw and little else. Fast forward a few years. I’ve completed my degree and I’m teaching. A student was in her second class with me and one day after class she said, “Dr. Kenney, I’ve noticed that you talk about woodworking a lot in your examples and explanations. Is that something you like to do?” After I told her that it was, she said, “My dad is a professional furniture make but thinks he’s a philosopher. Would you like to meet him?” (I was a professional philosopher who thought he was a furniture maker.) I went to meet her dad, he took me into his shop and taught me how to make furniture Two and half years later, I was an editor at Fine Woodworking. In the last eight and half years, I’ve learned a ton and built a lot of furniture and boxes. Working at the magazine has been a wonderful education.

What is your biggest influence?

This is a tough question, because there have been many significant influences in my woodworking life: my dad, my friend Joe Mazurek (the guy in SC who taught me to make furniture), and Mike Pekovich, my colleague at Fine Woodworking. My dad gave me a passion for making, and the dexterity and mechanical intuition necessary to work well with tools. Joe taught me the fundamentals of furniture making, and asked for nothing in return. I learned a ton about technique from Mike, too, and he has been a wonderful sounding board through the years. We talk about design together, and I often run construction strategies and techniques by him. It’s a phenomenal benefit to work with someone who is as passionate about woodworking and as active in the shop as I am. It doesn’t hurt that he’s one of the best furniture makers I’ve ever met. In terms of design, it’s the Shakers. I lover their mastery of proportion and color, and how they used doors and drawers to create beautiful arrangement of shapes (I think of them as geometric patterns) in their furniture.

What is the biggest obstacle you overcame to get to where you are, woodworking or otherwise?

I don’t know. I believe it’s impossible to appreciate the true magnitude of our accomplishments. I’ve met many people who have thought it a big deal that I earned a Ph. D., or that I work at Fine Woodworking, but from my perspective, it’s just my life. I wanted to earn a Ph. D. In philosophy, so I worked hard to do it. I made choices during my life that put me in a position to be a good candidate for a job at the magazine, and when I got the job I worked hard. Perhaps I’ve just been lucky or privileged, and have not faced any true obstacles, but I doubt it. It’s more likely that I don’t realize them as obstacles because when I confronted them, I put my head down, got focused, got determined, and worked. And when I had overcome them, I pushed on. It’s a matter of perspective. From where I stand, I don’t see obstacles. I see goals and figure a way to achieve them. A person standing outside my life would be better at identifying the obstacles I’ve had to overcome, perhaps. I realize I’m not answering your question. Sorry.

Is your design process more spontaneous or meticulous?

I’m meticulous. I do a lot of quick sketches, attempting to get down as many variations on a central idea as I can. I then pick the few I like to most and sketch them more carefully. From there I pick the one I want to build, sketch it with greater precision, giving attention to proportions. Next, I make very careful and proportionally correct drawings to nail down the actual dimensions. Finally, I’ll create measured drawings. I don’t believe in happy accidents in design. I want to know precisely what I am going to make when I start. I like my design to be deliberate, and I don’t like being forced to make design choices because I’ve worked my way into a corner (this happens when you design on the fly). This gives me the best chance of creating something beautiful and fully realized.

Which is more important to you: beauty or utility?

Beauty. I want to make beautiful things. But here’s the sticky wicket: A piece of furniture isn’t truly beautiful if it is not useful. So, I strive to make useful beauty, beautiful utility. I want the utility and beauty of my furniture to dance effortlessly together.

Have you developed your own style? What makes your work your own?

I think I have. My guess is that my boxes are fairly distinct from what others are doing. I strive to make boxes (and furniture) that are subtle and quietly beautiful. I focus on proportion, and using the parts of a box to create a pattern. And I like using color (milk paint or fabric) to emphasize this pattern. But I don’t know. This is probably a question better answered by someone else, who can look at my work and compare it the work of others from the outside. It’s hard to see your own nose.

How does your training in philosophy influence your woodworking?

Lord, I don’t know. Philosophy is the exercise of critical reasoning in an unflinching search for truth about our humanity, and our place in the universe. I suppose that philosophy helped me to better understand what it means to be human, and woodworking allows me to express this understanding in a tangible way. Creativity, an appreciation for beauty, technical knowledge: these are all part of what it means to be human. And so woodworking is an expression of our humanity. Here I am again not answering your question. Philosophy doesn’t necessarily influence my woodworking, but because of my background in philosophy I am better able to understand why woodworking is so important to me. I am better able to appreciate why craft is a valuable human endeavor.

What did you take away from the 52 Boxes project? (I loved reading about that, by the way. I also enjoy making boxes, and took inspiration from the beauties you made)

Well, the answer to this question is at least one book. I’ll try to keep it short, though. The first thing: If you want to get good at design, you better practice it on a regular basis. Design something and make it. Design something else, and make it, too. Do it a third time, a fourth time, and so on. The second thing: simplicity is always better than complexity. This is true of design, technique, and construction. It’s also true of our lives. The third thing: Discipline is good. Honestly, I knew this already. If you want to achieve anything you must be disciplined and focused. Get in the shop everyday and work. The fourth thing: trust your passion. I love to make boxes. Previously, I had been a bit hesitant to embrace this, but part of why I did the 52 boxes project was because I just wanted to make what I had a passion for instead of what others considered “true” woodworking or furniture maker. I trusted myself and it turned out well. I discovered that there are others out there who liked my box making. That’s a good feeling. It’s also led to a book, a gallery exhibition, and several commissions. Do what you love and good things will follow. Unless you love something bad, like crushing goldfish under your boot. That’s evil, and you’re a jerk. Don’t do that. The fifth thing: 52 boxes take up a lot of space.

Can you sum up your philosophy about woodworking in just a few words?

There is a voice inside each of us. Listen to yours. Discover what it has to say about beauty. Take this knowledge and use it to create furniture that you love. Let your passion for the craft guide you in the shop. And if someone gets in the way, tell them to go kiss a goat.

So I decided to try to make contact with many of the woodworkers from whom I have learned, primarily from the pages of Fine Woodworking Magazine. Luckily, woodworkers are generally a very friendly and generous lot, and nearly all of those I contacted were more than willing to help, despite their busy schedules. In fact, more replied than I had weeks in which to write. I noticed that my interviewing skills improved with time. The first interview I did, was far too scripted, and I regret that. The questions I had were too generic, and I didn’t do enough to respond to answers with thoughtful follow-up questions. In subsequent interviews, though, I learned from the questions that were not very effective and thought of new ones to ask instead. I also got better at just listening to what was being said rather than thinking ahead too much to the next question. I did my best to stay true to what was said in each conversation based on my notes and memory, and I apologize for any errors.

So I decided to try to make contact with many of the woodworkers from whom I have learned, primarily from the pages of Fine Woodworking Magazine. Luckily, woodworkers are generally a very friendly and generous lot, and nearly all of those I contacted were more than willing to help, despite their busy schedules. In fact, more replied than I had weeks in which to write. I noticed that my interviewing skills improved with time. The first interview I did, was far too scripted, and I regret that. The questions I had were too generic, and I didn’t do enough to respond to answers with thoughtful follow-up questions. In subsequent interviews, though, I learned from the questions that were not very effective and thought of new ones to ask instead. I also got better at just listening to what was being said rather than thinking ahead too much to the next question. I did my best to stay true to what was said in each conversation based on my notes and memory, and I apologize for any errors.  It has already been influenced by the professionals I learned from, and it will undoubtedly evolve. I am so greatly influenced by the work of the woodworkers I plan to interview that I want to know more about their history, thought processes, and philosophy. Hopefully, by the end of these ten weeks, I will have gained a deeper understanding of how I have come to think and work as I do. I don’t know if it will work out that way. If it doesn’t, something else of great value will certainly come of this project. In the course of writing this post, I have already learned something about myself. That alone is worth a lot.”

It has already been influenced by the professionals I learned from, and it will undoubtedly evolve. I am so greatly influenced by the work of the woodworkers I plan to interview that I want to know more about their history, thought processes, and philosophy. Hopefully, by the end of these ten weeks, I will have gained a deeper understanding of how I have come to think and work as I do. I don’t know if it will work out that way. If it doesn’t, something else of great value will certainly come of this project. In the course of writing this post, I have already learned something about myself. That alone is worth a lot.” They love to do work for themselves, to explore their passions and interests, but also value teaching, and passing on skills to other makers. They love to work by hand, but recognize the necessity of doing some machine work to be efficient enough to be successful in the modern marketplace. In their willingness to talk to a young woodworker about their craft, I see a desire to pass on their passion to a younger generation so that it might continue to thrive.

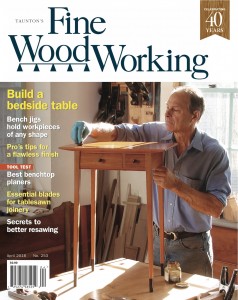

They love to do work for themselves, to explore their passions and interests, but also value teaching, and passing on skills to other makers. They love to work by hand, but recognize the necessity of doing some machine work to be efficient enough to be successful in the modern marketplace. In their willingness to talk to a young woodworker about their craft, I see a desire to pass on their passion to a younger generation so that it might continue to thrive.  Mike Pekovich is a professional woodworker and executive art director at Fine Woodworking Magazine. He is highly respected by his colleagues as one of the best furniture makers around.

Mike Pekovich is a professional woodworker and executive art director at Fine Woodworking Magazine. He is highly respected by his colleagues as one of the best furniture makers around.  He favors simple designs that perform a function, with the philosophy that unless a piece is useful it cannot be beautiful. In his words: “ultimately both are important, and a piece lacking in either isn’t worth making or owning.” Beauty is a very subjective thing, of course, but in my opinion, an object is more likely to hold a broad appeal if it is very simple, quiet, and functional.

He favors simple designs that perform a function, with the philosophy that unless a piece is useful it cannot be beautiful. In his words: “ultimately both are important, and a piece lacking in either isn’t worth making or owning.” Beauty is a very subjective thing, of course, but in my opinion, an object is more likely to hold a broad appeal if it is very simple, quiet, and functional. Only when a fault or failure is recognized can it be corrected, and Mike helps himself through this process by doing drawings and mockups whose flaws are easier to recognize and correct than a piece into which months of blood, sweat, and tears have been poured. Still, the mistakes and flaws that do make it into a final product are important, as “those [pieces] are the ones that haunt me and challenge me to do better next time.”

Only when a fault or failure is recognized can it be corrected, and Mike helps himself through this process by doing drawings and mockups whose flaws are easier to recognize and correct than a piece into which months of blood, sweat, and tears have been poured. Still, the mistakes and flaws that do make it into a final product are important, as “those [pieces] are the ones that haunt me and challenge me to do better next time.”

Teaching is stressful because it takes a lot of effort, but the satisfaction of seeing someone learn or refine a skill makes it worthwhile. In general, Mike describes his work as his own “because I have made it with my hands to suit my eye.” Beyond that, he does have a recognizable style, influenced directly by the arts and crafts and Japanese motifs.

Teaching is stressful because it takes a lot of effort, but the satisfaction of seeing someone learn or refine a skill makes it worthwhile. In general, Mike describes his work as his own “because I have made it with my hands to suit my eye.” Beyond that, he does have a recognizable style, influenced directly by the arts and crafts and Japanese motifs.

His education is in philosophy, and I wondered how that affects his woodworking. In answer, it doesn’t directly: “Philosophy doesn’t necessarily influence my woodworking, but because of my background in philosophy I am better able to understand why woodworking is so important to me. I am better able to appreciate why craft is a valuable human endeavor.” He is able to convey these thoughts very well in writing as well. Despite not proofreading his responses to my questions, he wrote quite eloquently about his journey as a woodworker and his philosophy and process. Matt’s full responses are at the bottom of the post.

His education is in philosophy, and I wondered how that affects his woodworking. In answer, it doesn’t directly: “Philosophy doesn’t necessarily influence my woodworking, but because of my background in philosophy I am better able to understand why woodworking is so important to me. I am better able to appreciate why craft is a valuable human endeavor.” He is able to convey these thoughts very well in writing as well. Despite not proofreading his responses to my questions, he wrote quite eloquently about his journey as a woodworker and his philosophy and process. Matt’s full responses are at the bottom of the post. He survived to graduate high school and went on to study philosophy in college and graduate school. In the course of pursuing his doctorate, he married and started to build a few projects for his home, including a gardening tool box and crib with basic tools. Once again, he was “hooked” on woodworking. At this point, Kenney had become a professor. By chance, the father of one of his students was a furniture maker. As the student put it, “My dad is a professional furniture maker but thinks he’s a philosopher,” and Kenney was the inverse. He went to meet and learn from that furniture maker, and a few years later went to work at Fine Woodworking as an editor. In each of these three stages of development as a woodworker, he was influenced by a different person who each played a very important role in helping Kenney to reach the level at which he works today.

He survived to graduate high school and went on to study philosophy in college and graduate school. In the course of pursuing his doctorate, he married and started to build a few projects for his home, including a gardening tool box and crib with basic tools. Once again, he was “hooked” on woodworking. At this point, Kenney had become a professor. By chance, the father of one of his students was a furniture maker. As the student put it, “My dad is a professional furniture maker but thinks he’s a philosopher,” and Kenney was the inverse. He went to meet and learn from that furniture maker, and a few years later went to work at Fine Woodworking as an editor. In each of these three stages of development as a woodworker, he was influenced by a different person who each played a very important role in helping Kenney to reach the level at which he works today.  In his younger years, his dad taught him to be interested in building things and to work with tools. As an adult, his student’s father showed him the fundamentals of building quality furniture. And now at Fine Woodworking, Mike Pekovich (see next week) is his design mentor.

In his younger years, his dad taught him to be interested in building things and to work with tools. As an adult, his student’s father showed him the fundamentals of building quality furniture. And now at Fine Woodworking, Mike Pekovich (see next week) is his design mentor. This influence is evident in most of his designs, but I asked Matt if he believes that he has developed his own style. “I think I have. My guess is that my boxes are fairly distinct from what others are doing. I strive to make boxes (and furniture) that are subtle and quietly beautiful. I focus on proportion and using the parts of a box to create a pattern. And I like using color (milk paint or fabric) to emphasize this pattern. But I don’t know. This is probably a question better answered by someone else, who can look at my work and compare it the work of others from the outside. It’s hard to see your own nose.” I have to say that I agree, he has developed his own style.

This influence is evident in most of his designs, but I asked Matt if he believes that he has developed his own style. “I think I have. My guess is that my boxes are fairly distinct from what others are doing. I strive to make boxes (and furniture) that are subtle and quietly beautiful. I focus on proportion and using the parts of a box to create a pattern. And I like using color (milk paint or fabric) to emphasize this pattern. But I don’t know. This is probably a question better answered by someone else, who can look at my work and compare it the work of others from the outside. It’s hard to see your own nose.” I have to say that I agree, he has developed his own style. The milk paint used sparingly in many of his pieces is part of what sets his style apart from that of the Shakers. The simple appearance of Kenney’s work conceals the skill and precision that he puts into building each piece, as well as his meticulous design process. He spends time iterating through a series of ever-more specific sketches and plans before working with the wood. He wants to be sure that there are no unforeseen difficulties as he builds a piece. Doing design this way makes it most likely that he will have a good result. He makes sure that beauty is the focus of his designs, but a piece can’t be beautiful unless it is also useful: “So, I strive to make useful beauty, beautiful utility. I want the utility and beauty of my furniture to dance effortlessly together.”

The milk paint used sparingly in many of his pieces is part of what sets his style apart from that of the Shakers. The simple appearance of Kenney’s work conceals the skill and precision that he puts into building each piece, as well as his meticulous design process. He spends time iterating through a series of ever-more specific sketches and plans before working with the wood. He wants to be sure that there are no unforeseen difficulties as he builds a piece. Doing design this way makes it most likely that he will have a good result. He makes sure that beauty is the focus of his designs, but a piece can’t be beautiful unless it is also useful: “So, I strive to make useful beauty, beautiful utility. I want the utility and beauty of my furniture to dance effortlessly together.” Over the course of the project he was not only reminded of the importance of practicing design but of other lessons on life and woodworking both: “simplicity is always better than complexity,” discipline is essential to success, and trusting a passion leads to good outcomes.

Over the course of the project he was not only reminded of the importance of practicing design but of other lessons on life and woodworking both: “simplicity is always better than complexity,” discipline is essential to success, and trusting a passion leads to good outcomes.  by Kenney. He designed the box in the lower left of the cover. When I look back on that article in comparison to the very first boxes of the 52 Boxes Project (more than three years later), it is stunning to see the difference in Kenney’s style, initially rather generic, which further develops into something particularly distinct by the end of the year. Always technically sound and useful, his box making, in my opinion, is now genuinely beautiful.

by Kenney. He designed the box in the lower left of the cover. When I look back on that article in comparison to the very first boxes of the 52 Boxes Project (more than three years later), it is stunning to see the difference in Kenney’s style, initially rather generic, which further develops into something particularly distinct by the end of the year. Always technically sound and useful, his box making, in my opinion, is now genuinely beautiful.  and is well known for his large number of bandsaws.

and is well known for his large number of bandsaws.  That man showed him the shop and the program, and Fortune switched majors immediately, without looking back. After school, there was a little difficulty getting started. Fortune’s practical skills were not as refined as his design ones were, so he had to work hard and practice to build them up and become a great furniture designer and maker.

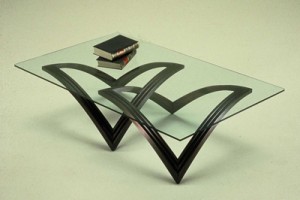

That man showed him the shop and the program, and Fortune switched majors immediately, without looking back. After school, there was a little difficulty getting started. Fortune’s practical skills were not as refined as his design ones were, so he had to work hard and practice to build them up and become a great furniture designer and maker.  Peters showed him how to make an entire project his own rather than let it be controlled by a client. Like me, Fortune picked up much of his woodworking knowledge from Fine Woodworking Magazine, which at the time had just been created. Today he frequently writes for the magazine, helping to teach young woodworkers like me. He also pay the favor of Alan Peters forward by hosting interns in his shop so that they can gain experience in designing and building. Fortune still remains in control of what he builds. He takes an need and very basic requirements from a client, prepares two drawings, and the client can pick one or the other, nothing else. It took time to gain this confidence, but it has worked out very well. The clients are willing to trust him, and he does things this way because he is the one trained in design and construction, not the client. He knows what will work and what won’t. And he knows how to make something beautiful. Fortune’s work is modern but doesn’t have the hard lines found in much modern furniture as a result of factory production. He loves to work with curves and bends. His design process is very iterative, he uses drawings and multiple scale models before doing any real woodwork.

Peters showed him how to make an entire project his own rather than let it be controlled by a client. Like me, Fortune picked up much of his woodworking knowledge from Fine Woodworking Magazine, which at the time had just been created. Today he frequently writes for the magazine, helping to teach young woodworkers like me. He also pay the favor of Alan Peters forward by hosting interns in his shop so that they can gain experience in designing and building. Fortune still remains in control of what he builds. He takes an need and very basic requirements from a client, prepares two drawings, and the client can pick one or the other, nothing else. It took time to gain this confidence, but it has worked out very well. The clients are willing to trust him, and he does things this way because he is the one trained in design and construction, not the client. He knows what will work and what won’t. And he knows how to make something beautiful. Fortune’s work is modern but doesn’t have the hard lines found in much modern furniture as a result of factory production. He loves to work with curves and bends. His design process is very iterative, he uses drawings and multiple scale models before doing any real woodwork.  In addition to helping paying clients who woodwork as a hobby, he has spent time helping underprivileged people in developing countries, teaching how to design, woodwork, and market their furniture and products to be commercially successful.

In addition to helping paying clients who woodwork as a hobby, he has spent time helping underprivileged people in developing countries, teaching how to design, woodwork, and market their furniture and products to be commercially successful.

for its own line of tools that they design and manufacture to high standards in Canada, called Veritas, or “truth” in Latin. The company was founded by Robin’s father, Leonard Lee. Leonard grew up on a homestead with very limited means. He and his family had to make do with what they had in their work on the farm and the home. When Robin was young they lived on a farm, working with their hands and building things all the time.

for its own line of tools that they design and manufacture to high standards in Canada, called Veritas, or “truth” in Latin. The company was founded by Robin’s father, Leonard Lee. Leonard grew up on a homestead with very limited means. He and his family had to make do with what they had in their work on the farm and the home. When Robin was young they lived on a farm, working with their hands and building things all the time. Still, he loves his job because of the culture present at Lee Valley. Employees are treated as family, the same as customers, and interacting with them is very enjoyable. The challenge of the job is creating a good product that allows a sense of trust to build between company, employee, and customer. As an organization so connected to the customer base, that relationship influences the creation and modification of tools. They listen to the customer base and act accordingly.

Still, he loves his job because of the culture present at Lee Valley. Employees are treated as family, the same as customers, and interacting with them is very enjoyable. The challenge of the job is creating a good product that allows a sense of trust to build between company, employee, and customer. As an organization so connected to the customer base, that relationship influences the creation and modification of tools. They listen to the customer base and act accordingly. The values behind the company are what makes the tools Veritas, though. It is more important to satisfy the customer than focus on making a profit. By doing the former, the latter occurs naturally, albeit slowly for the most part. In doing the right thing for business, employee, and customer alike and rectifying mistakes, Lee Valley fulfills its responsibility to those dependents in the interest of stability and long-term viability.

The values behind the company are what makes the tools Veritas, though. It is more important to satisfy the customer than focus on making a profit. By doing the former, the latter occurs naturally, albeit slowly for the most part. In doing the right thing for business, employee, and customer alike and rectifying mistakes, Lee Valley fulfills its responsibility to those dependents in the interest of stability and long-term viability. I asked Robin if there was competition between the two companies. In answer, he said that of course there is a little bit of competition because they both serve the woodworking hand tool market, but the styles they cater to are different, and in general woodworkers have some tools from each company. Robin actually uses some Lie-Nielsen tools in his shop.

I asked Robin if there was competition between the two companies. In answer, he said that of course there is a little bit of competition because they both serve the woodworking hand tool market, but the styles they cater to are different, and in general woodworkers have some tools from each company. Robin actually uses some Lie-Nielsen tools in his shop.  And the whole piece was done mostly by hand. This opened my eyes even more to the power of hand tools. The chest is representative of Hunter’s work as a whole, with his focus on simple, clean designs made mostly by hand.

And the whole piece was done mostly by hand. This opened my eyes even more to the power of hand tools. The chest is representative of Hunter’s work as a whole, with his focus on simple, clean designs made mostly by hand. After graduating, he went straight to a cabinet shop for work, never using his degree in the workplace. He learned a lot in that shop, but it was not how he preferred to work. His first tools personal tools included a drill, a circular saw, a hand saw, chisels, and a Stanley plane. With such a limited selection of tools he was forced to learn hand skills, which became his main method of work. Hunter also has a lot of experience with carpentry and timber framing, having done it in the past and occasionally in the present to help make ends meet since the money is better and more steady in that industry than in fine furniture making.

After graduating, he went straight to a cabinet shop for work, never using his degree in the workplace. He learned a lot in that shop, but it was not how he preferred to work. His first tools personal tools included a drill, a circular saw, a hand saw, chisels, and a Stanley plane. With such a limited selection of tools he was forced to learn hand skills, which became his main method of work. Hunter also has a lot of experience with carpentry and timber framing, having done it in the past and occasionally in the present to help make ends meet since the money is better and more steady in that industry than in fine furniture making.  As a result, he is used to using hand tools to shape pieces and dealing with corners that are not square.

As a result, he is used to using hand tools to shape pieces and dealing with corners that are not square.  This led to an interest in the design and woodwork of the area. The designs of the Japanese are simple and consist of clean lines while the Japanese are more complex in their designs and joinery. Aside from the design and methods of work of Asia, Hunter is particularly attracted to the philosophy of Asia, including Buddhism, that is behind the designs and methods of work. Craftsmen in that region do their work with a sense of presence and zen that Hunter also seeks, and that is well suited to work with hand tools.

This led to an interest in the design and woodwork of the area. The designs of the Japanese are simple and consist of clean lines while the Japanese are more complex in their designs and joinery. Aside from the design and methods of work of Asia, Hunter is particularly attracted to the philosophy of Asia, including Buddhism, that is behind the designs and methods of work. Craftsmen in that region do their work with a sense of presence and zen that Hunter also seeks, and that is well suited to work with hand tools.  He uses them as much as possible for the rough milling of lumber and tasks such as mortising, which are extremely labor intensive and can be quite dull. To do them by hand would also not be effective economically. Hand tools complement the machines and take the work to the next level, as he cuts joinery and planes the surface of boards. For these tasks the piece does not have to be machine square, giving him a lot more freedom to work.

He uses them as much as possible for the rough milling of lumber and tasks such as mortising, which are extremely labor intensive and can be quite dull. To do them by hand would also not be effective economically. Hand tools complement the machines and take the work to the next level, as he cuts joinery and planes the surface of boards. For these tasks the piece does not have to be machine square, giving him a lot more freedom to work.  Woodworking is a battle with the wood which the craftsman wins by being highly skilled. Those hand skills are being lost today as craftsmen move toward machines with more power, capable of doing the work more quickly and with less effort. In an effort to return the focus of the craft to skill and intimacy, Hunter is very involved in teaching. He makes sure that hand skills are still appreciated and in use. He is also exposing the Western world to the tools and designs of Asia, which are not widely known but are beautiful and have distinct advantages. Hunter likes to say that woodworking should be about “blades, not buttons,” and is working to make the statement more true in the modern age.

Woodworking is a battle with the wood which the craftsman wins by being highly skilled. Those hand skills are being lost today as craftsmen move toward machines with more power, capable of doing the work more quickly and with less effort. In an effort to return the focus of the craft to skill and intimacy, Hunter is very involved in teaching. He makes sure that hand skills are still appreciated and in use. He is also exposing the Western world to the tools and designs of Asia, which are not widely known but are beautiful and have distinct advantages. Hunter likes to say that woodworking should be about “blades, not buttons,” and is working to make the statement more true in the modern age.  Variations of the Windsor have been made for centuries, but the basic features are turned and steam-bent pieces that attach to a carved seat. A picture does not give the Windsor chair its due justice. A truly great chair must be seen in person in order to be fully appreciated.

Variations of the Windsor have been made for centuries, but the basic features are turned and steam-bent pieces that attach to a carved seat. A picture does not give the Windsor chair its due justice. A truly great chair must be seen in person in order to be fully appreciated.  He had to wait until he was in college to start woodworking again, and he hasn’t stopped since. Fortunately, he feels the same immersion and contentment today as he did in his middle school days, but only because he has found his passion within woodworking.

He had to wait until he was in college to start woodworking again, and he hasn’t stopped since. Fortunately, he feels the same immersion and contentment today as he did in his middle school days, but only because he has found his passion within woodworking. I asked him if the focus on Windsor chairs ever gets boring. In answer, it doesn’t, because there are so many modifications that can be made to the style, so many things to try. He can make an old style into something unmistakably his own. The style is not so much limiting as a way of working. And that gives limitless opportunity.

I asked him if the focus on Windsor chairs ever gets boring. In answer, it doesn’t, because there are so many modifications that can be made to the style, so many things to try. He can make an old style into something unmistakably his own. The style is not so much limiting as a way of working. And that gives limitless opportunity.  Even though it is modern, it makes the process easier but doesn’t go so far as making it a production process. He considers himself to be a tinkerer rather than an engineer, but solving problems brings him joy. In the same way that Galbert isn’t paid enough to work entirely with traditional methods, he can’t be paid enough to use power tools extensively in the making of a chair. This statement from his website sums it up: “

Even though it is modern, it makes the process easier but doesn’t go so far as making it a production process. He considers himself to be a tinkerer rather than an engineer, but solving problems brings him joy. In the same way that Galbert isn’t paid enough to work entirely with traditional methods, he can’t be paid enough to use power tools extensively in the making of a chair. This statement from his website sums it up: “ It’s also the most fun way of doing things because the best process involves lots of handwork and a deep connection with the wood. The chairs need to be comfortable and strong and beautiful, of course, but in Galbert’s mind, the most important thing is that the chair be fun to make, as he has to do it day after day.

It’s also the most fun way of doing things because the best process involves lots of handwork and a deep connection with the wood. The chairs need to be comfortable and strong and beautiful, of course, but in Galbert’s mind, the most important thing is that the chair be fun to make, as he has to do it day after day.  The tool marks and grain are still very tactile, at the same time feeling silky smooth. He believes that it takes a fine designer’s eye to make full use of the natural beauty of wood, and most people are woodworkers first and designers second.

The tool marks and grain are still very tactile, at the same time feeling silky smooth. He believes that it takes a fine designer’s eye to make full use of the natural beauty of wood, and most people are woodworkers first and designers second.  Naturally, I looked toward FWW for advice about what to look for in a plane and which models performed best. Chris Gochnour, a professional woodworker and hand tool expert from Salt Lake City, Utah, wrote one of the articles I relied on. He authors many of the tool reviews and tests in the magazine and uses them extensively as he builds his pieces.

Naturally, I looked toward FWW for advice about what to look for in a plane and which models performed best. Chris Gochnour, a professional woodworker and hand tool expert from Salt Lake City, Utah, wrote one of the articles I relied on. He authors many of the tool reviews and tests in the magazine and uses them extensively as he builds his pieces.  Doing work to the specifications and aesthetic preferences of others does not really leave room for the development of an individual style. Gochnour initially started woodworking in high school, when his first job involved building custom longboards and snowboards (which he still builds occasionally today). After earning a degree in English Literature he started building furniture for a living. Early on, he spent time in England. He was young and impressionable, but also at the early stages of his woodworking career. The experience did expose him to different styles and culture and a very old tradition. He was happy to be working in America, though, because living and working in England is extremely expensive and the market is small.

Doing work to the specifications and aesthetic preferences of others does not really leave room for the development of an individual style. Gochnour initially started woodworking in high school, when his first job involved building custom longboards and snowboards (which he still builds occasionally today). After earning a degree in English Literature he started building furniture for a living. Early on, he spent time in England. He was young and impressionable, but also at the early stages of his woodworking career. The experience did expose him to different styles and culture and a very old tradition. He was happy to be working in America, though, because living and working in England is extremely expensive and the market is small.  It is all that most people want or need. Gochnour only ever advertised his work once, in the classified section of the newspaper. Out of that came nearly a year of work, and after that the commissions were steady. He got to the point of having so much work that he had to take deposits to make sure it would still be there when he got around to it. Times have changed, and such an abundance of commissions is no longer available unless one is as well established as Gochnour is. Even though work is available to him, it is less interesting because it is commissioned by rich clients for whom money is no object. They are buying custom furniture for their second homes and don’t really care too much about it. The good thing is they don’t ask questions. They aren’t a joy to work with as the middle class was.

It is all that most people want or need. Gochnour only ever advertised his work once, in the classified section of the newspaper. Out of that came nearly a year of work, and after that the commissions were steady. He got to the point of having so much work that he had to take deposits to make sure it would still be there when he got around to it. Times have changed, and such an abundance of commissions is no longer available unless one is as well established as Gochnour is. Even though work is available to him, it is less interesting because it is commissioned by rich clients for whom money is no object. They are buying custom furniture for their second homes and don’t really care too much about it. The good thing is they don’t ask questions. They aren’t a joy to work with as the middle class was.  But now Gochnour is well established. He isn’t taking commissions for the time being. Instead, he is teaching at several local schools, giving private lessons in his shop. He also writes for magazines such as Fine Woodworking. This gives him a steady salary and set hours. It is somewhat more difficult to maintain his skills, though, as doing so requires consistent effort and challenge.

But now Gochnour is well established. He isn’t taking commissions for the time being. Instead, he is teaching at several local schools, giving private lessons in his shop. He also writes for magazines such as Fine Woodworking. This gives him a steady salary and set hours. It is somewhat more difficult to maintain his skills, though, as doing so requires consistent effort and challenge.  Woodworking is not an easy path to follow, especially today. In Gochnour’s opinion, it is more prudent in modern times to hold a stable, traditional job and do woodworking on the side. The dream of being a professional woodworker may no longer be so attainable, but there will always be a great multitude of hobbyist woodworkers. That’s a very good thing. And they should use hand tools.

Woodworking is not an easy path to follow, especially today. In Gochnour’s opinion, it is more prudent in modern times to hold a stable, traditional job and do woodworking on the side. The dream of being a professional woodworker may no longer be so attainable, but there will always be a great multitude of hobbyist woodworkers. That’s a very good thing. And they should use hand tools.

Neither can be executed well without a strong understanding of the materials and techniques that contribute to them. There are also limits to the aesthetic of a piece. Going too far makes it impossible for the piece to constructed soundly or practically. And, as in any business, the process is important. There are different ways to reach the same outcome visually and structurally, some being simpler than others.

Neither can be executed well without a strong understanding of the materials and techniques that contribute to them. There are also limits to the aesthetic of a piece. Going too far makes it impossible for the piece to constructed soundly or practically. And, as in any business, the process is important. There are different ways to reach the same outcome visually and structurally, some being simpler than others.  There is really no such thing as specialization in woodworking, as quality work comes from accomplishment in many different areas. Hack also travels the world teaching about woodworking. It creates some balance in his life and allows him to learn about new cultures and bring back inspiration for his work. It is essential for him to continue innovating by integrating new ideas and more difficult components into his work. I concluded by asked what he considered to be the most crucial quality for a woodworker. His answer was perseverance. It takes time and practice and expense and frustration to become a master of the craft. Garrett Hack has done so.

There is really no such thing as specialization in woodworking, as quality work comes from accomplishment in many different areas. Hack also travels the world teaching about woodworking. It creates some balance in his life and allows him to learn about new cultures and bring back inspiration for his work. It is essential for him to continue innovating by integrating new ideas and more difficult components into his work. I concluded by asked what he considered to be the most crucial quality for a woodworker. His answer was perseverance. It takes time and practice and expense and frustration to become a master of the craft. Garrett Hack has done so.  I built a model lighthouse out of balsa wood and popsicle sticks, using Exacto knives to cut the pieces. With the next Christmas came a drill and a jigsaw, and as a result, a much more sophisticated model lighthouse from plywood disks.I started to find videos on the internet about woodworking, produced by The Wood Whisperer, Fine Woodworking online, and others. That led me to Fine Woodworking Magazine, borrowed from the public library. I made every effort to read every issue, but they might as well have been written in a foreign language. Tenons, rabbets, fillets, mortises, dovetails, biscuits, laps, dados, planes, routers – the specialized

I built a model lighthouse out of balsa wood and popsicle sticks, using Exacto knives to cut the pieces. With the next Christmas came a drill and a jigsaw, and as a result, a much more sophisticated model lighthouse from plywood disks.I started to find videos on the internet about woodworking, produced by The Wood Whisperer, Fine Woodworking online, and others. That led me to Fine Woodworking Magazine, borrowed from the public library. I made every effort to read every issue, but they might as well have been written in a foreign language. Tenons, rabbets, fillets, mortises, dovetails, biscuits, laps, dados, planes, routers – the specialized  vocabulary goes on and on. The pictures and captions saved me, allowing me to associate words with their physical manifestations in woodworking. I became fluent in this strange new language and devoured every magazine and TV show I could find. Without ever having access to a real suite of woodworking tools, I had all of the theory necessary for basic woodworking stored in my head. Theoretically, I knew how to operate the tools, how to cut joints, and how to finish a piece.

vocabulary goes on and on. The pictures and captions saved me, allowing me to associate words with their physical manifestations in woodworking. I became fluent in this strange new language and devoured every magazine and TV show I could find. Without ever having access to a real suite of woodworking tools, I had all of the theory necessary for basic woodworking stored in my head. Theoretically, I knew how to operate the tools, how to cut joints, and how to finish a piece. My maternal grandfather worked out of a gigantic, high-ceilinged shop space, and focused on antique furniture repair and projects closer to carpentry. Unfortunately, my paternal grandfather passed away before I came of age or expressed interest in woodworking (which, paradoxically, is the reason I have a shop full of tools with which to work). My other grandfather didn’t spend much time in his shop once I was old enough, and was unwilling to teach me to use the tools because they are dangerous. This I understand, but it meant that I was on my own in learning to woodwork.

My maternal grandfather worked out of a gigantic, high-ceilinged shop space, and focused on antique furniture repair and projects closer to carpentry. Unfortunately, my paternal grandfather passed away before I came of age or expressed interest in woodworking (which, paradoxically, is the reason I have a shop full of tools with which to work). My other grandfather didn’t spend much time in his shop once I was old enough, and was unwilling to teach me to use the tools because they are dangerous. This I understand, but it meant that I was on my own in learning to woodwork. I built a desktop organizer, a music box, a side table, all from a set of detailed plans. With each, I used nice wood and included complex components. For my first foray into woodworking, I suppose I did okay. Looking back today, though, I see gappy joints and rough surfaces. Generally, the details didn’t matter to me, either because I didn’t have the skill or tool to properly execute what I was attempting or because I was impatient to move on to the next step and finish the piece. I find this to be an issue for me still today. I always attempt to incorporate elements beyond my skill level so that I might continue to improve, and I always fall at least a little short of success. This is unavoidable as I seek to improve, so I can accept less than perfection. But patience is something I need to work on. The quality of my woodwork could improve greatly if I were to take the time to do everything to the best of my ability. As the years passed, my projects got more complex, more ambitious, more useful, and more beautiful. My knowledge remained robust, but my practical skill expanded greatly. And that is what really matters.

I built a desktop organizer, a music box, a side table, all from a set of detailed plans. With each, I used nice wood and included complex components. For my first foray into woodworking, I suppose I did okay. Looking back today, though, I see gappy joints and rough surfaces. Generally, the details didn’t matter to me, either because I didn’t have the skill or tool to properly execute what I was attempting or because I was impatient to move on to the next step and finish the piece. I find this to be an issue for me still today. I always attempt to incorporate elements beyond my skill level so that I might continue to improve, and I always fall at least a little short of success. This is unavoidable as I seek to improve, so I can accept less than perfection. But patience is something I need to work on. The quality of my woodwork could improve greatly if I were to take the time to do everything to the best of my ability. As the years passed, my projects got more complex, more ambitious, more useful, and more beautiful. My knowledge remained robust, but my practical skill expanded greatly. And that is what really matters. The magazine emphasizes the necessity of hand tools to truly fine woodworking. I picked up on this philosophy and fell in love with the idea of quality, and expensive, tools. Neither of my grandfathers was particularly interested in hand tools. Their shops were essentially devoid of them, and what they did have were of low quality or rusted over or both.

The magazine emphasizes the necessity of hand tools to truly fine woodworking. I picked up on this philosophy and fell in love with the idea of quality, and expensive, tools. Neither of my grandfathers was particularly interested in hand tools. Their shops were essentially devoid of them, and what they did have were of low quality or rusted over or both.  Despite the lacking of my hand tools, the quality of my work was much improved, and I recognized first hand that the return on investment in a quality tool more than made up for its price. I picked a plane that I felt would be most useful and decided it would be my first purchase, whenever the time came. After a backbreaking day of shoveling snow, I decided to reward myself by using the day’s earnings to purchase that plane. Every day I spend in the shop includes some use of that tool. It is critical to my work, and likely will always be. The same is true of the other hand tools in which I have since invested.

Despite the lacking of my hand tools, the quality of my work was much improved, and I recognized first hand that the return on investment in a quality tool more than made up for its price. I picked a plane that I felt would be most useful and decided it would be my first purchase, whenever the time came. After a backbreaking day of shoveling snow, I decided to reward myself by using the day’s earnings to purchase that plane. Every day I spend in the shop includes some use of that tool. It is critical to my work, and likely will always be. The same is true of the other hand tools in which I have since invested.  I am so greatly influenced by the work of the woodworkers I plan to interview that I want to know more about their history, thought processes, and philosophy. Hopefully, by the end of these ten weeks, I will have gained a deeper understanding of how I have come to think and work as I do. I don’t know if it will work out that way. If it doesn’t, something else of great value will certainly come of this project. In the course of writing this post, I have already learned something about myself. That alone is worth a lot.

I am so greatly influenced by the work of the woodworkers I plan to interview that I want to know more about their history, thought processes, and philosophy. Hopefully, by the end of these ten weeks, I will have gained a deeper understanding of how I have come to think and work as I do. I don’t know if it will work out that way. If it doesn’t, something else of great value will certainly come of this project. In the course of writing this post, I have already learned something about myself. That alone is worth a lot.