Everyone has a mother.

Every mother has gone through the decidedly difficult process leading up to, during and after childbirth. Unfortunately, many mothers around the world experience extremely hostile conditions in every stage: emotionally, physically, and socially.

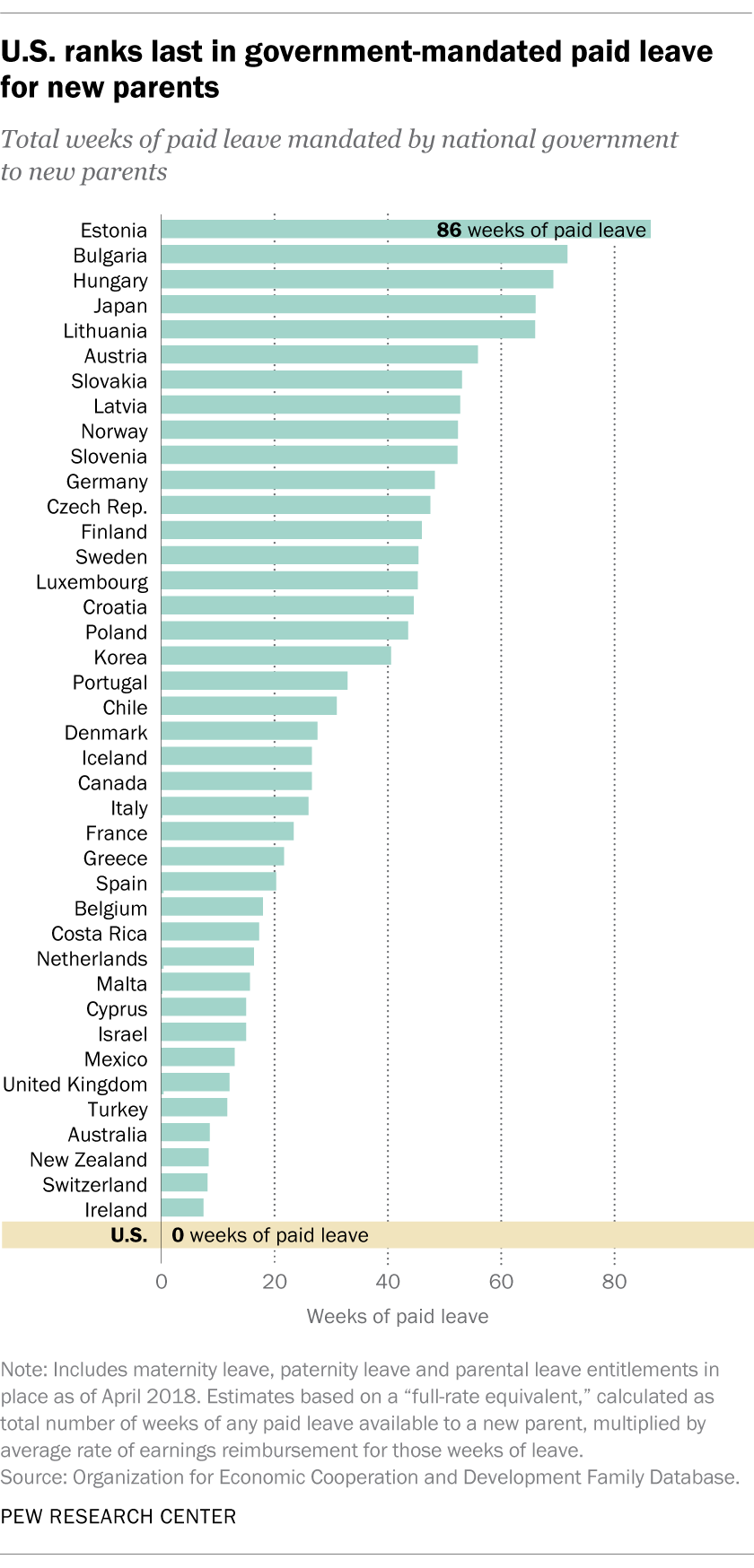

Recovery after childbirth is so vital to the mother (as well as the child) but around the world many mothers are not afforded the time for recovery. 120 countries, including most industrialized countries, require paid maternity leave but the US is not one of them.

In Britain, a working mother has 39 weeks of paid maternity leave (90% typical salary for six weeks and a lower percentage for the remaining time determined by the employer). Sweden allows for 68 weeks and Estonia gives 82 weeks “includ[ing] ‘a one-off payment at birth and additional support for families with more than three children, families with children with disabilities, and low-income families.’” (Washington Post).

The US has 0 weeks.

Although “96% of Democrats say mothers should get paid leave” and a whopping 88% of Republicans agree”, there is still not legally mandated paid maternity leave in the US (Business Insider 7). Joe Pinsker, a writer for the Atlantic, writes about the lack of maternity leave in the US. Pinsker emphasizes that the pandemic has highlighted the need for such a policy (Pinsker 4). The article also quotes Richard Petts, a sociologist at Ball State University, who says that researchers have acknowledged the benefits of paid maternity leave for decades (Pinsker 5). But this is not enough to convince US legislation.

If the US can claim to fight for womens’ rights this invariably ought to include the policy of paid maternity leave. While we have advanced in terms of women permeating the workforce, we have not reconciled the idea of the woman as the mother within the workforce. Every person has an identity or character within what they do, within their profession but equally as paramount is their identity within their family. But neither ought to overshadow the other. It is presumptuous to think that a job should take a higher priority for a woman than her children just as it is presumptuous to think that a child should restrict a mother from pursuing her professional dream. A professional woman does not require refusal of children and a good mother does not require a lack of profession.

The professional environment cannot ignore or disrespect the other identities of women. Whether a real estate agent, psychologist, professor, teacher etc., each profession must acknowledge that a woman with children has another role aside from the professional area. It must acknowledge and then accommodate. To refuse paid leave to a pregnant woman/woman with a newborn is to restrict the identity of her motherhood. It is to isolate the maternal from the professional.

If the professional environment cares about the wellbeing of those in it, it would implement a policy for maternity leave. Bleeding gum, body aches, swelling, back pain, and vaginal pain only cover the physical effects of pregnancy. Mentally, mothers can undergo anything from anxiety to postpartum depression. But the US would respond to all this by saying “Your time to adjust to being a mother is not important to us, so come back quickly to where you do have importance.” The lack of maternity leave is detrimental to the child as well. It is no secret that bonding after pregnancy between mother and child is crucial. The “brain development of infants…pends on a loving bond or attachment relationship with a primary caregiver, usually a parent” (NCBI). Yet, the legislative face of the US cannot serve the new mother or her child.

What prevents it? Why is it so difficult? An NPR article reflects on different possibilities for this roadblock. Perhaps, it proposes, it is due to the focus on individualism in America. America specializes in catering to the individual’s professional dream, not a familial one. Another reflection proposes that post World War II, as men were reclaiming their working positions and women returning to domestic positions, there was no incentive to “create policies that helped [women] stay in the workplace” (NPR). But if the US is really pushing for women to be in the professional field, we cannot use this archaic reason.

If the US is pushing for women in the workforce, it must also be for mothers in the workforce. The US should not expect women to prioritize their professional lives over their personal lives. If the professional sphere of the US is truly a place for women, why does it ask them not to be mothers?

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/11/11/global-paid-parental-leave-us/

https://www.pewPaid parental leave around the world and how the US compares – The Washington Postresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/FT_19.10.28_PaidLeave.png

https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/FT_19.10.28_PaidLeave.png

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/11/us-paid-

https://www.parents.com/pregnancy/my-body/postpartum/your-postpartum-body-what-to-expect-and-what-to-do/https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/postpartum-depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20376617#:~:text=Most%20new%20moms%20experience%20postpartum,for%20up%20to%20two%20weeks.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5330336/

Of 41 countries, only US lacks paid parental leave | Pew Research Center