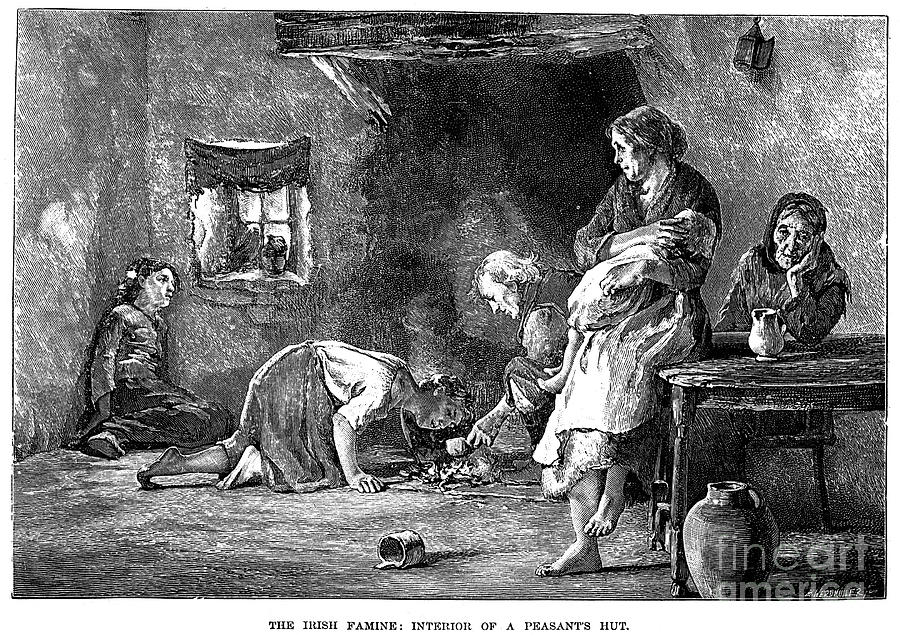

Probably the most infamous and heartbreaking event in Irish history, The Great Famine was a period of Irish history occurring from 1845 to 1852 in which nearly 75% of the Irish potato crop was destroyed by the mold Phytophthora infestans. It led to an estimated one million Irish casualties from starvation and related causes, with at least another million forced to flee the country as refugees, a substantial population ending up in America in what became known as The Great Migration. Several factors contributed to this disaster, both agricultural and societal, and the aftermath of the Famine has been felt for centuries since.

Phytophthora infestans infestation of a potato. Source: Google Images

Agricultural causes of the Great Famine are much more straightforward than their socio-political counterparts. As previously stated, the death of the potato crop was that of the Phytophthora infestans, which is an oomycete or water mold that primarily attacks potatoes and tomatoes. It produces dark green spots that then turn brown and black on the surface of the leaves and stems of the potato plants. The potato itself has stunted growth and black rot around the edges and seeping into its core. Phytophthora originated in Central Mexico and spread to Ireland through imported potato seeds and tubers which infect fully grown plants. Since the potato crop in Ireland was largely asexually reproduced, the potato crop were genetic clones of one another. Since there was very little genetic diversity, the mold was able to sweep its way across Ireland with very little internal pushback from the crop itself. As discussed in the Week Three post, the farmers and lower class of Ireland relied heavily on the potato crop for food since other, more desirable crops were shipped away to the weather British class.

A less considered component of the Great Famine was the role the British Government played in the leadup to and devastation during the Famine itself. In addition to keeping the lower class almost entirely reliant on the potato crop, British lawmakers had decreed that it was illegal for people of the Catholic faith to own their land. Since Catholicism was the dominant religion of Ireland, this meant most of the population had to give up large portions of their crop yield, including the potato crop, to the British landowners. Thus, when The Famine occurred, all “good crops” were sent away from Ireland, further depleting the food sources of the Irish. In cases of other commodities such as livestock and dairy experts believe that agricultural exports from Ireland may have increased during the Potato Famine, further bleeding out the crop supply of the Irish people. While the country of England did repeal such laws as the “Corn Laws” and grain tariffs, the damage they had been afflicting for centuries had taken its heavy toll, many families had no choice by to flee.

Illustration of Irish Peasants life during the famine. Source: Google Images

The lack of food and aid set many Irish families to flee their beloved homeland, and The Great Migration saw 1-2 million Irish people emigrate to North America and Great Britain. Even in the Great American Melting Pot, however, the Irish were treated harshly and isolated by the other dozens of ethnic groups that came to America in the 19th century. The Irish formed close-knit communities and soon became the largest European ethnic group to emigrate in the world, establishing close connections and aid networks for their homeland.

Sources:

Glynn, Irial. “Irish Emigration History | University College Cork.” University College Cork, 2017, www.ucc.ie/en/emigre/history/.

History.com Editors. “Irish Potato Famine.” HISTORY, A&E Television Networks, 17 Oct. 2017, www.history.com/topics/immigration/irish-potato-famine.

Mark Thornton. “What Caused the Irish Potato Famine? | Mark Thornton.” Mises Institute, 17 Mar. 2017, mises.org/library/what-caused-irish-potato-famine.

Mokyr, Joel. “Great Famine | History, Causes, & Facts.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 Jan. 2019, www.britannica.com/event/Great-Famine-Irish-history.

Portrait of Irish Parliament,

Portrait of Irish Parliament,