My name is Audrey Hiller and I am going into my junior year as a Plant Science major with a focus in Horticulture. Earlier this May, I traveled to Ireland with eighteen of my fellow Penn State students and three professors as a part of our HORT 499: Spring Travel to Ireland course. While over there, we spent seven days touring the country and exploring culture, cuisine, history, and landmarks. We visited agricultural areas like the National Botanical Gardens, the Victorian Kitchen Garden, and the Powerscourt House and Gardens, where we walked through and learned about Ireland’s expansive and beautiful flora, both native and exotic. We learned about the cuisine and beverages iconic to Ireland, including tours of the Guinness Storehouse and Kilbeggan Whiskey Distillery. We also spent our free time in the evenings exploring the various towns and cities we stayed in, speaking to locals, shopping in the Dingle shopping districts, and visiting the various historical bars, restaurants, and pubs that line the Irish streets. We also visited many stops along the beautiful Irish landscape, including the Dingle Peninsula, the Cliffs of Moher, and the Burren, a beautiful rocky expanse of limestone overlooking the sea. My favorite part of the trip was the several historical stops and institutions that we explored. I have always been interested in history, especially political and cultural history, and Ireland’s relationship with Britain and the social, religious, and cultural fallout has fascinated me. As I walked through the ruins of castles and monasteries and cathedrals, as I visited the National Museum and Kilkenny, Blarney, and Bunratty Castles, I learned and absorbed as much Irish history, art, and culture as I could. Our tour guide, Sean, would tell us stories and tales of the history of the British occupation of Ireland as we drove through the beautiful countryside and bustling towns. Being immersed in that level of history and culture was a dream come true, and I am so happy to have experienced it all.

If I had to explain this experience to a potential employer, I would have to describe it as an eye-opening absorption of culture. By attending this trip, I learned how to navigate foreign situations and customs and I embraced new situations, foods, and activities. This trip allowed me to get out of my comfort zone and experiment with new experiences. I hope to carry these new skills with me as I grow and learn through my adult life, and I look forward to applying these skills to situations and milestones as they arise in my life.

Left: Me standing at the shoreline near the Burren

Center: Armeria maritima at the Burren

Right: A castle at the Cliffs of Moher

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/4GSDAPXK5GXLNXTNF7IQELPXU4.jpg)

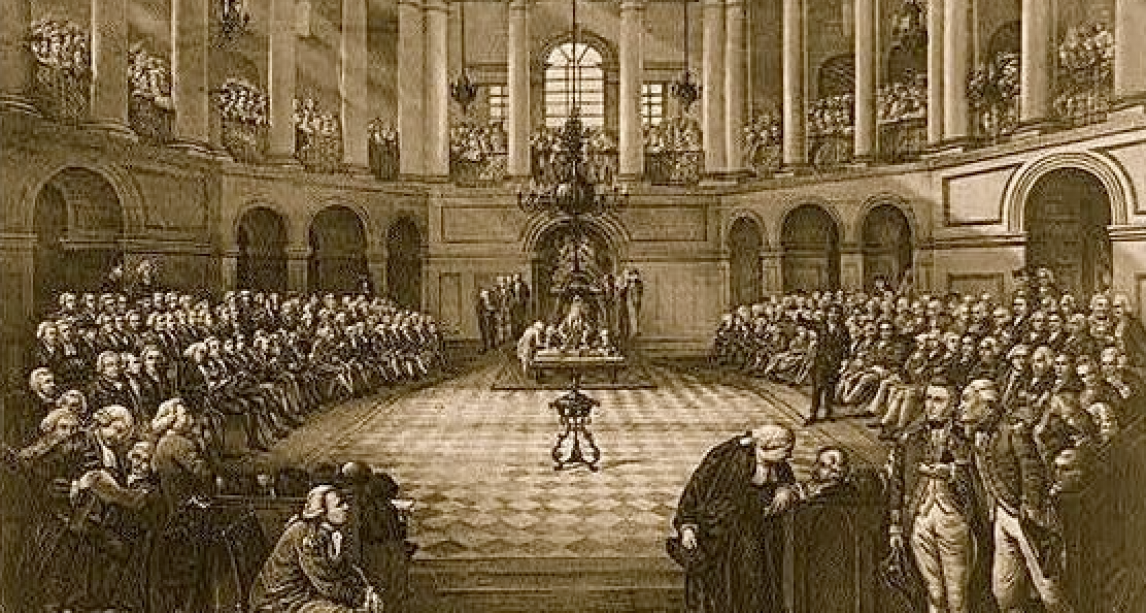

Portrait of Irish Parliament,

Portrait of Irish Parliament,