In my last blog, I discussed how the growing wealth gap in the United States became so enormous in the first place. I discussed the impact of tax cuts, productivity, lobbying, and restrictions on unions. I talked about how these issues have caused the rich to become richer and the middle class to sink into poverty. Yet, what are the actual implications of America’s income gap? How has this affected your average, everyday American?

The Middle Class

The middle class, over time, has been shrinking while simultaneously getting poorer and poorer. The widening of the income gap and the shrinking of the middle class has led to a steady decrease in the share of U.S. aggregate income held by middle-class households. In 1970, adults in middle-income households accounted for 62% of aggregate income, a share that fell to 42% in 2020 (Pew Research Center). Middle-income Americans have fallen further behind financially in the new century. In 2014, the median income of these households was 4% less than in 2000. Furthermore, because of the housing market crisis and the Great Recession of 2007-09, their median wealth (assets minus debts) fell by 28% from 2001 to 2013 (International Monetary Fund).

The middle class is a representative of the center of society. Before income inequality became so apparent, the middle class served an important role in our economic system. It is not so economically precarious that middle-class Americans feel powerless and completely dependent on gifts from others. They had the time to look up political candidates and make an educated vote, or read the news, and they had room to take risks, such as starting a business or inventing something new.

However, nowadays being “middle class” means something entirely different. Families, as I’ve mentioned before, experience limited income growth over time, making it challenging to keep up with rising costs of living, inflation, and unexpected expenses. This is why both the recession of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic hit the middle class so hard- because so much of the nation’s income is taken up by the top 1%, that the class we intend to be the most stable is highly unstable in today’s economy. And considering how many Americans are in the middle class, the issue of income inequality is affecting your average, everyday citizen. Inflation has skyrocketed, and now people cannot afford housing, education, hospital bills, etc. Their incomes were meant to adjust for that increase in prices over the years. But it hasn’t. Because (as I talked about in my last post) people are not being paid for their increase in productivity. People’s real wages are decreasing by the second, and that money is instead going to the extremely rich. If the middle class is so affected by this issue, you can only imagine how it would affect the lower class.

The Lower Class

12.4% of Americans now live in poverty according to new 2022 data from the U.S. census, an increase from 7.4% in 2021. Child poverty also more than doubled last year to 12.4% from 5.2% the year before. The U.S. poverty level is now $13,590 for individuals and $23,030 for a family of three (U.S. Census Bureau). According to the latest ACS data, nearly 41 million people in the United States lived below the poverty line in 2022. That is nearly 1.5 million more people than in 2019, before the pandemic struck. The COVID crisis has exacerbated inequalities between the very wealthy and the rest of the population, and similarly to the middle class, the lower class has become extremely unstable.

As shown by the graph, the ideal economic system that 92% of citizens agree on is a system in which nobody falls below the poverty line. This is far, far from our reality. Each year, more and more people are falling from the middle class to the lower class, and even more are falling below the poverty line. The lower class, just like the middle class, is incredibly unstable due to its minuscule share of the nation’s wealth as well as little to no political power. The lower, working class does not have the resources to fight against poverty. The government will keep ignoring poverty, as long as the upper-class keeps funding that ignorance and continues to lobby politicians. Poverty is a vicious cycle that has only been exasperated by the recent trends in income inequality.

The Upper Class

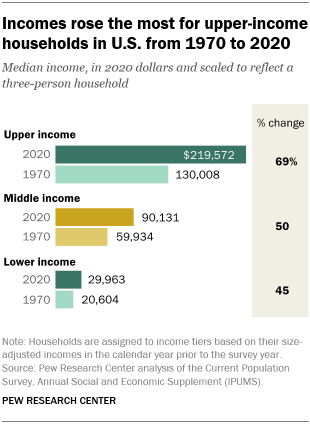

The rise in income from 1970 to 2020 was steepest for upper-income households. Their median income increased 69% during that timespan, from $130,008 to $219,572 (Pew Research Center). As I talked about in my last post, the ultra-rich hold political power, in which they are able to receive tax-cuts and restrict their workers from receiving proper compensation for the immense growth in productivity over the years. Instead, they take that compensation for themselves. Even worse, the general public does not recognize this. The human mind cannot fully comprehend large numbers, and therefore we largely underestimate how rich the rich actually are. Billionaires could bring thousands upon thousands of families out of debt with a tiny fraction of their income. They could invest that money in small businesses, workers, etc to fuel the working class… but most don’t. As they say, “There is no ethical billionaire”.

They have made it there by exploiting their workers, not compensating them, and then keeping the general public in the dark about how they make their money. They focus their agenda on policies that will benefit them, instead of the general public. This is also a cycle- when the rich are continuously empowered, both financially and politically, they will continue to do things that benefit them and only them, while simultaneously hurting everyone else. There is no incentive to stop. And there is no incentive for the government to do anything about it, because these are the people that hold political power. Not the middle class. Not those suffering from poverty. This issue is byproduct of the very fundamental flaws our system of government and economic system have. Until those flaws are resolved, income inequality will continue to rage on.