Usually when I meet someone for the first time, they ask me “what is your ethnic background?” With my long dark hair and almond eyes, most people guess Hispanic, but the bright green eyes throw them off. When I answer, they are always surprised. I start with the most prevalent parts of my ethnic heritage, Italian and Irish from my Dad’s side of the family. And then I tell them that I am also part Japanese. “Wow Japanese!”, they say, “That is so interesting. You don’t really look Japanese!” Personally, I love being Japanese and having a heritage from a culture with so many time-honored traditions. Maybe it’s because being part Japanese is something that has actually shaped a lot of my personality. Or maybe it’s the story of why I am Japanese and how my grandmother came to be an American that makes me love it so much.

My grandmother was born and raised in Kobe, Japan in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Her family was a part of Japan’s Samurai class, one of the highest and oldest social classes in Japanese culture. In her social class, she didn’t attend an outside school. Instead, she and her sister had a governess and tutors that taught them all of their subjects. During World War II, after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States bombed Japan in retaliation. Running to a bomb shelter during one of the US bombing raids, my grandmother was injured by shrapnel from one of the bombs. She carried a long scar on her forehead for the rest of her life.

(my grandma and her sister as little girls)

After World War II and the dropping of the world’s first atomic bombs at Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan was devastated and came under occupation by the US military beginning in the mid 1940’s. There was no food, no industry, and it was very difficult for the Japanese people to survive, so the US helped Japan to rebuild. During the 1950’s, the US was involved in the Korean Conflict and Japan was used a staging area for US military operations in Southeast Asia. My grandfather, born and raised in West Virginia, was a Navy SEAL who was stationed in Japan during the US occupation. While on leave in Tokyo, my grandparents met by chance at a party. To me, they seem like an unlikely pair: the petite, quiet 20-something daughter of a Japanese samurai and the tall, larger-than-life All-American Navy SEAL. But I guess love knows no limits. When my grandfather told this story, he always said that “the room lit up when my grandmother walked in.” They fell madly in love and wanted to get married as soon as they could.

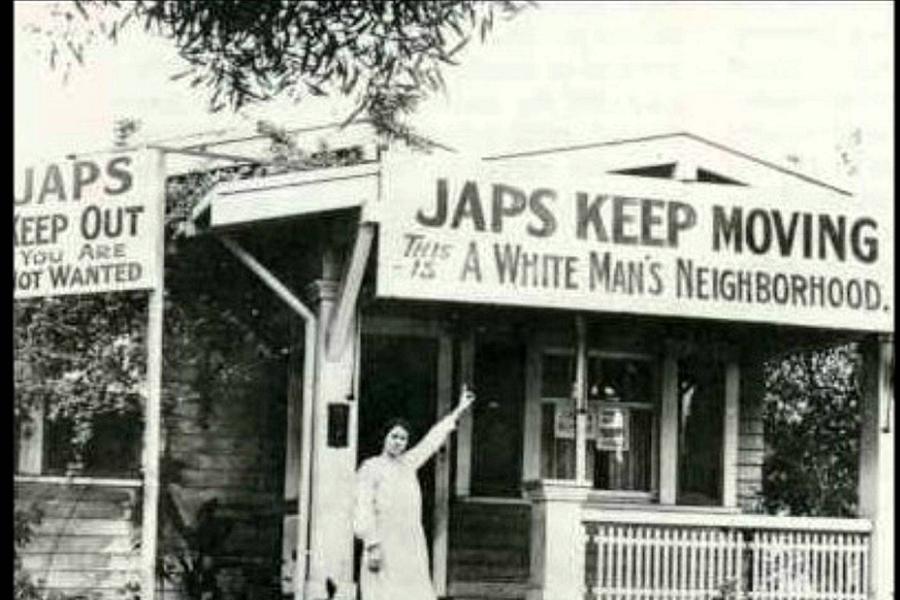

Unfortunately, at the time, the US government was not supportive of Japanese citizens marrying Americans. After the War, hatred of Japan and all things Japanese was at an all-time high. The Japanese had killed many Americans during the War, including during the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a large US navy base in Hawaii. In America, the government was so upset and nervous about the Japanese that they imprisoned all American citizens who were of Japanese descent in concentration camps, known as “internment camps”, in remote parts of the US, like the one in Manzanar in California. These innocent Americans were required to move to the camps with very little notice. They lost their homes and all of their possessions just because they were of Japanese descent. When they were moved to the internment camps, they could take almost nothing with them, only what they could physically carry. Historical accounts of life in the internment camps describe the horrendous living conditions, the poor sanitation, and the unfairness of the situation. These people went from being normal American citizens, working and going to school and church, to living in a make-shift prison just because of their race and ethnic heritage. For me, the scariest part of this history is that had I been alive at that time, I too would have been forced to these camps, along with my grandmother, my mother and my sister. My Dad would not have been allowed to come with us. It’s hard for me to imagine being told that I am no longer a “real” American and to move to a concentration camp.

(Image 1: Stockton, Richard. “True Stories Of The Japanese-American Internment Program From Those Who Lived Through It.” All That’s Interesting, All That’s Interesting, 10 Feb. 2017, allthatsinteresting.com/japanese-american-internment-program.)

But even after the War and the closure of the Japanese internment camps in 1945, the US was still suspicious of Japanese citizens. When my grandparents met in the 1950’s, there were strict rules about marrying a Japanese woman if you were American military personnel. My grandfather had to ask for permission by filing a plan to marry with the US government, and then waiting for at least a full year before marrying. In the meantime, the American had to go back to the US and stay there without his fiancé for the entire year. If they still wanted to get married after that, then the American was allowed to go back to Japan and find their love. Keeping a long-distance relationship going is hard even today with instant communication at our fingertips via cell phones, texting and social media. Back then, the only communication for an entire year would have been handwritten letters. The government assumed that most couples wouldn’t stay together after 12 months apart. The goal was to end any fling that a military person had, remind them of the “good life” in the US, and ultimately, to not have Japanese people become a part of American culture.

Thankfully, my grandparents beat out the wait and married about a year later. However, this didn’t come without many hardships. My grandmother’s family was very upset that she wanted to marry an American boy. So mad, in fact, that they disowned her from her family, Samurai class, and any Japanese connection at all. She left Japan with my grandfather and a small bag of kimonos and few pieces of jewelry and not much else. Arriving in the US, it wasn’t much better for her. There was so much hatred and discrimination against the Japanese that she changed her name from “Kimiko”, a traditional Japanese name, to “Nancy” just to fit in. Lots of my grandfather’s family, including his own brother, refused to acknowledge their wedding or her existence as a person just because she was a “Jap”. To this day, I have never met some family members, on both my grandmother’s side and my grandfather’s side of the family. Even my mother, who was born in the United States, has never met her uncle, my grandfather’s brother, or her aunt, my grandmother’s sister. My great-uncle refuses to meet anyone who has part “Jap” in them, even if it is only half. And no one knows what my great-aunt thinks since she refused to communicate with my grandmother after she left Japan.

My grandmother never wanted us to travel to Japan and see Kobe or Tokyo again. She always said that there was nothing there for any of us. I cannot imagine being in my grandmother’s shoes during those times. Not only losing your family, and having people refuse to meet you because of your heritage, and no doubt getting denied jobs because of your race, but to deal with assimilating into American culture at this time too.

In those days, a Japanese person was not seen as a real person. Regardless of whether you were full Japanese or just part, or married to one of the bravest and most respected Navy heroes, you were still a disgrace, just because of your race and ethnic heritage.

Today, I take pride in my heritage and race. I am grateful for the hardships that my grandmother endured and proud of her courage and fearlessness in facing a New World where she was not accepted for who she was. Those who were able to see past that racism met a wonderful, funny, smart woman who was comfortable and respectful to everyone from dignitaries to janitors. I am just as proud of my grandmother’s Asian blood as my grandfather’s American blood, if not more so.