Overview

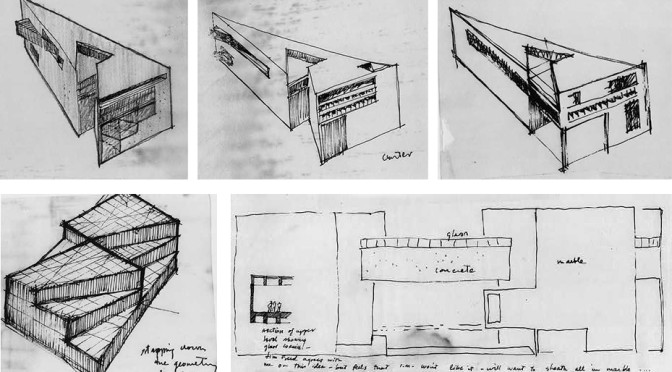

Creating a multipurpose building for the Greenpoint community through reuse of the existing transport washing station is Rebecca’s main intent in her design project. First, extending the walls of the corner closest to the intersection to complete the rectangular shape of the station also generates the apparatus bays necessary to house the fire station. A transparent seam between the new construction and historical brick accentuates this new addition. The station’s large footprint is utilized by incorporating multiple public programs and organized by historical paths reestablished within the station’s interior as well as continuing throughout the rest of the site. The fire station’s more privatized areas are raised using the current structural columns; creating easy access to the apparatus bay when fire service is required. Visually separate flying trusses above the roof are to support any new additions as well as create an additional public realm underneath.

Presentation of Work

Rebecca speaks very confidently and presents her decisions regarding her design well.

Each individual drawing segregated her boards. Plans read the clearest. Line weights were well pronounced and dedicated areas with precision of her hand drawings. Sections were a little unclear; although the section cuts were, and any building behind them was very hard to discern. What I found to need the most explanation was the many colors used to envelope the elevations. There were many and what they represented was lost. Adding a color key or labeling of their respectability would make their intent easier to read (The colors were not discussed in the presentation either).

The Review

After Rebecca’s presentation, the reviewers focused on industrial and civic values in critiquing her design. Considering the majority of her building is pre-determined through the existing wash station and most interventions require new structure to accommodate the relevance of her structural systems is impertinent to her design. Rebecca’s largest intent in the reuse of the station is for the public’s interest, and to best serve the community the reviewers engaged at the prospects of creating a desired community space.

Although most of the critique followed on the idea of emphasizing current design proposals, which would be fame oriented, the intent is to emphasize the structural and civic implications not emphasize the design itself.

“Bedrooms need windows.”

To meet code, each individual bedroom needs one door and window. It would also create a healthier environment for the fire fighters by adding natural lighting into their private rooms. More lighting would be accessible if the mezzanine like floor encompassed the space instead of crossing through it. I believe that even in keeping its current design, if other means of lighting (mentioned later) are enhanced in the interior, the bedrooms could stay in their location in order to not interfere lower level programs.

Accentuate Existing vs. New Renovation

Rebecca’s interstitions are new and enhance the existing setting. Show how they improve the current situation by emphasizing their difference. The reviewers recommended that in drawing, Rebecca’s renovations be poched while the old was hard lined.

Strengthen/Emphasize Gestures

The reviews admired the gesture of renovating the existing building along with the site and wanted Rebecca to increase her efforts on this front. It was called a “pretentious site.” Trying to understand what was meant, I believe that the reviewer was trying to explain how the building wants to assume a greater importance. The large pathway that connects the street to the park was remarked as an important gesture of “giving the street back” to the public. They recommended enlarging it to accentuate the connection between the street and the inlet. In enlarging the opening, this invites the public into the building while also adding natural lighting into the interior.

Though within the same building, the station and public quarters are separate (separated by the aforementioned pathway). To continue the connection the pathway creates within the building, the roof between the fire station and public areas should also be emphasized. This could be instituted by intervening with the roof itself above the pathway’s opening. Rebecca already has occupied open levels above to interact with the existing roof. Interacting with design to emphasize the difference between the areas that have more interventions (the fire station part) vs. the eastern public realm by adding another transitional seam as she did between the apparatus addition and existing building would continue her efforts in expressing new vs. existing in a singular approach.

“Making a Clear Site Plan Should Be Next Step”

The multiplicity of pathways are excessive and created too small of exterior recreational spaces. Not much was discussed regarding any advised changes to Rebecca’s site within the critique otherwise. To make the design whole, I recommend emphasizing the public access way down to the water’s edge, and not to focus on a continuing line of other historical pathways. Not dismissing them, but by continuing each pathway through another is where the divisions create insufficient plots of land to use. Trees could replace lesser important paths to continue the form of any division used within the building as they could form linear qualities as well as vertical divisions.

“Support Looks Questionable”

Can the existing columns support the additional loads? I personally know with being in Rebecca’s section that she has continuously been monitoring the existing building’s ability to hold the new renovations. Considering the question arose very strongly in discussion, the means for displaying its ability to withstand intervention is crucial. By addressing the size of the columns within plan or perhaps wall section it would display knowledge of the forces acted upon the structure. A load diagram using the flying trusses would also show their importance and how the building functions structurally.

Need for Natural Lighting

The building’s size would not allow for much light penetration even if the majority of the walls were replaced with glass. The reviewers recommended interior courtyards that allow light to access interior floors from an open roof source. Implementing such a suggestion would also help to designate areas on the occupiable roof(s).

Conclusion

The reviewers as well as myself believe Rebecca has developed a “good system of intervention.” The main weaknesses in her design were the need to continue the strength of her current operations. By emphasizing differences in new vs. existing and the connections made in the public realm within the site, the design would reach stronger clarity. Any gestures made have been solid so far and only need to be pushed further to express the desired intent.

Featured Image: Artscape Wychwood Barns by DTAH, 2011

Maintenance facility from 1913 converted into mixed-used public center.