PROPOSED PERIODICAL: CITY LAB

On July 18, 2013, the city of Detroit filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy. A city that once was bustling with citizens and a booming automotive industry has since suffered economic turmoil. Its people left after the success of the postwar years, a 63% decrease in population since 1950 (Hobbs and Stoop 2002). Most startling is the amount of unused, abandoned land. There are currently 78,000 structures accompanied by 66,000 lots currently sitting idle, falling to ruin in the city of Detroit. These abandoned sites become magnets for violent crimes, but through adaptive reuse they could see an alternative fate of bringing sustainability, cultural value, and economic development to Detroit. Rather than allowing old, industrial buildings to fall to ruin, the city of Detroit should incentivize private investors to revitalize these buildings to become sustainable and viable centers of activity through adaptive reuse.

Detroit needs revitalizing through adaptive reuse. Adaptive reuse is the act of creating new built opportunities within existing built forms, often abandoned and in unceasing decay. Adaptive reuse can accommodate for the social, political and economic progress within a community. It is found most often that abandoned, industrial buildings are located in prime, dynamic spaces such as along a waterfront or in proximity to historic landmarks. It is a sustainable approach for architectural design, especially in cities such as Detroit.

There are crucial steps to successfully implement adaptive reuse projects in Detroit. The first step is to evaluate existing conditions. Designers should thoroughly evaluate the existing fabric in order to make the most of the conditions and former structural, mechanical, electrical, architectural and landscape systems. The second step is to update systems to comply with current codes. Most issues with code compliance have to deal with energy standards, accessibility and fire regulations. The next step is to insert contextual program. The context must be highly considered in order to insert effective program. Industrial spaces are most effectively converted into to retail and community spaces.

Why is adaptive reuse the solution to Detroit?

An existing building has ecological, cultural, economic, and financial value. Instead of inevitably becoming a burden on a community, an industrial building can serve as a hub for urban life and create opportunities for natural urban development.

- Sustainability. Reusing the existing structure decreases the environmental damage resulting from transportation and production of materials.

- Improving cultural value and identity. Enhancing the identity of a culture maintains history and memory in place while providing new function for its survival. Bringing authenticity to a site also acknowledges the significance of an existing use and space.

- Embracing development of economy. Repurposing a building helps accommodate cultural changes because “Adaptive re-use projects speak to a wider cultural shift – from an industrial and manufacturing based economy to one centered around services, education and cultural life” (Harrison 2014).

- Net cost can be less than new construction. Consuming less energy and using fewer building materials, the net cost of an adaptive reuse project can be less than new construction (Thornton 2011). Although sometimes the initial cost of adaptive reuse is more, as the cost of energy continues to rise, new construction becomes a more expensive option when considering its life cycle.

Other major cities have utilized adaptive reuse to capture these values that abandoned structures bring to urban life. Ghirardelli Square was the first successful example of adaptive reuse seen in the United States. In the 1960s, the existing factory buildings were

purchased by William Roth, who hired Lawrence Halprin, landscape architect, and Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons architectural firm to create a design to accommodate retail spaces, offices, restaurants and a movie theater (Sharpe 2012). This project preserved the history and authenticity of the site, prevented the demolition of a storied building, and developed a new economic center, serving as a strong example of values 2 and 3.

Across the country, the Brewery in Milwaukee presents a strong case for values 1, 2 and 3 in a very extensive and ambitious project that plans for the adaptive reuse and “environmentally sensitive restoration” amongst the remains of the Pabst Brewing Company (Benfield 2011).

The master plan of this project by Joseph Zilber includes residential lofts, a beer hall, office space, educational campuses, urban parks, senior living facilities, and medical campuses with more retail and luxury spaces to develop in the future. The success of this project relies on the cooperation between the developers, the city, and the LEED Neighborhood Development program. While this is a project under various stages of development, the existing structures that have been built have successfully brought community and life into a previously abandoned space.

In Detroit, Michigan Central Station and Harbor Terminal offer great opportunity for adaptive reuse because of their size, space and location. Michigan Central Station is a critical structure for adaptive reuse. With a space large enough for a train on the ground floor and an 18 story tower with hotel and office space above, this is prime real estate sitting vacant. An approach like that of Ghirardelli Square would be ideal, so that the history of the site and building may be preserved, bringing back the heyday of Detroit with a new era of use, featuring offices, retail space, and residential living. This site would be an excellent opportunity for all four values. Reusing existing structure conserves materials and cost. The quality and ornateness of existing materials are so expensive in today’s market, that this saves a quantifiable amount of money and preserves the original beauty. The cultural improvement will be immediately evident through restoration with a visual link to the history of Detroit. The creation of new retail space allows the community to effortlessly embrace new economic development.

Another potential site is the Harbor Terminal building. This huge warehouse currently sits vacant, but is an ideal candidate for adaptive reuse that could be turned into a multi-functional building with the creation of new waterfront urban space along the Detroit River as well. If the remains of the Pabst Brewing Company can be given a new life, why not this warehouse? While this could potentially be a more costly proposition, values 1, 2, and 3 could still be achieved. Materials would be conserved as the existing shell of the warehouse space allows for program to be directly inserted inside. By developing a new waterfront space, a new community center would be created along with a new economic hub and destination for not only residents of Detroit, but tourists as well.

The obstacle to implementing adaptive reuse in Detroit is the financial commitment needed to update systems and meet today’s code requirements. While preserving the history of a site is a very integral component of design, to private investors this does not always make adaptive reuse worth the financial obligations. Adaptive reuse can be a very financially involved and time intensive project. It is not always as simple as taking an old building and moving in new program. The mechanical and HVAC systems of these abandoned buildings are often out of date (if they even still function) and require extensive updates and installation of new modern systems. These systems are expensive to install for large buildings, and become even more expensive with the increase of sustainable measures (Donofrio 2012). Additionally, older buildings often do not meet today’s code and accessibility requirements. This may involve moving existing walls and structural elements in an attempt to make it compliant. While designers may love the opportunity to bring back the glory of an old architectural wonder, investors will often only see the dollars signs associated with doing such a task. For many investors it is cheaper to tear down a building and start from scratch. With all the necessary updates and adjustments that require extensive funds and construction, many say why bother with adaptive reuse?

Although the initial costs may be greater, the adaptive reuse of an existing building is the answer to revitalizing Detroit. For private investors who don’t see the value of cultural and historic preservation, there is a monetary incentive in place. For a site like Michigan Central Station on the National Register of Historic Places, a 20% income tax credit is available. Meanwhile, Harbor Terminal Building, being built before 1936, is eligible for a 10% income tax credit (U.S. National Park Service 2010). This program offered by the Internal Revenue Service and National Park Service encourages private sector investment in adaptive reuse that allows the preservation of historic sites, while creating jobs and revitalizing communities. Private investors and the local government can both benefit from a system like this.

Through the designer’s efforts to evaluate existing conditions, meet code compliance, and insert contextual program, adaptive reuse will offer an opportunity for Michigan Central Station and Harbor Terminal to revitalize the city of Detroit. Seeing the success of great urban works in cities such as Milwaukee and San Francisco, we believe adaptive reuse is the future for the success of revitalizing cities in our coming generation. We can take these old buildings, install updated systems, insert new program, and create a sustainable, viable space for the community. We believe that adaptive reuse could be just the change Detroit needs. While proposals have been made for sites such as Michigan Central Station, no actual renovation has begun. Through tax incentives, local government support, and community engagement, adaptive reuse can revitalize Detroit.

REFERENCES

Benfield, Kaid. “A Green Neighborhood Brewing in Milwaukee.” CityLab. The Atlantic, 22 Sept. 2011. Web. 25 Oct. 2015.

Binder, Melinda. “Adaptive Reuse and Sustainable Design: A Holistic Approach for Abandoned Industrial Buildings.” University of Cincinnati, 2003.

Hobbs, Frank and Stoops, Nicole. “Demographic Trends in the 20th Century; Census 2000 Special Reports” Decennial Census of Population, 1900 to 2000. U.S. Census Bureau, Nov. 2002. Web. 10 Dec. 2015.

Donofrio, Gregory. “Preservation by Adaptation: Is it Sustainable?” Change Over Time 2.2 (2012): 106-31.

Harrison, Stuart. Adaptive Re-use. Adelaide: Office for Design and Architecture, 2014. Odasa.sa.gov.au. Web.

Sharpe, Sara E., “Revitalizing Cities: Adaptive Reuse of Historic Structures” (2012). Mid-America College Art Association Conference 2012 Digital Publications. Paper 18.

Spivak, Jeffrey. “Adaptive Use Is Reinventing Detroit.” Urban Land Magazine. The Magazine of the Urban Land Institute, 14 Sept. 2015. Web. 24 Sept. 2015.

Thornton, BJ. “The Greenest Building (Is The One That You Don’t Build!) Effective Techniques for Sustainable Adaptive Reuse/Renovation.” Journal of Green Building 6.1 (2011; 1901): 1-7.

U.S. National Park Service. “Tax Incentives—Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010. Web. 09 Dec. 2015.

Featured Image by Zach Fein http://zfein.com/photography/detroit/mcs/index.html

oday, the subway system is recognized as the largest abandoned transit tunnel in the United States. Former Cincinnati mayor Mark Mallory has said, “Now more than forty percent of Cincinnatians do not know there is a subway system existing underneath Central Parkway Boulevard.” Rather than leaving the subway system to fall into further disrepair, the city of Cincinnati should restore and renovate the abandoned system to create a hub for community activity and interaction through adaptive reuse.

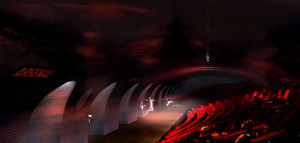

oday, the subway system is recognized as the largest abandoned transit tunnel in the United States. Former Cincinnati mayor Mark Mallory has said, “Now more than forty percent of Cincinnatians do not know there is a subway system existing underneath Central Parkway Boulevard.” Rather than leaving the subway system to fall into further disrepair, the city of Cincinnati should restore and renovate the abandoned system to create a hub for community activity and interaction through adaptive reuse.  ation projects in several of the tunnels. The most recent project was converting the space into a hydroponics center. This is an example of something that could easily be done in the Cincinnati tunnel system as well. Another example is the forsaken Paris Metro. These tunnels are currently in the planning stage and awaiting approval from the city. Current proposals for the tunnels include a restaurant, night club, performance center and theatre, a lap pool and installation spaces for art exhibits. All of these wide variety of programs are great examples of how flexible the spaces in the tunnels are for any possible idea of how they can be reused for new programmatic elements.

ation projects in several of the tunnels. The most recent project was converting the space into a hydroponics center. This is an example of something that could easily be done in the Cincinnati tunnel system as well. Another example is the forsaken Paris Metro. These tunnels are currently in the planning stage and awaiting approval from the city. Current proposals for the tunnels include a restaurant, night club, performance center and theatre, a lap pool and installation spaces for art exhibits. All of these wide variety of programs are great examples of how flexible the spaces in the tunnels are for any possible idea of how they can be reused for new programmatic elements.