Periodical: Post Magazine

Thesis: The architecture design process should manifest the cinematographic techniques used in filmmaking to better understand the spatial qualities of a design and communicate those qualities to the public.

Abstract: Architecture and cinema have been intrinsically connected since the creation of the moving image at the beginning of the 20th century. The moving image has the ability to direct people through spaces, engage their responsiveness and divert their attention – all at the same instance. The process and techniques used to bring a moving image to life and further engage it with a narrative is the practice of filmmaking. Why shouldn’t architecture follow this practice?

The filmmaking procedure is long and tedious. Much like architecture, impeding deadlines, revisions, and critiquing are all a part of the progression to a finished film. It is a product of industry, artistry and technology. The cooperative process between writers, producers, directors and actors is meant to extend to the audience as well, making them a vital part of the collaboration. Cinematographically representing architecture can be used as a way to approach the general public, thus giving architecture a broader audience and inviting them into its own collaboration process.

Architecture is integrally immersive and experimental – yet the conventions in which it is represented have not changed in centuries. While model making is a step forward in representing and communicating spatial ideas, film and animation can generate, develop and communicate these ideas in a way that is as immersive and experimental as the architecture itself, particularly to audiences without backgrounds in architecture.

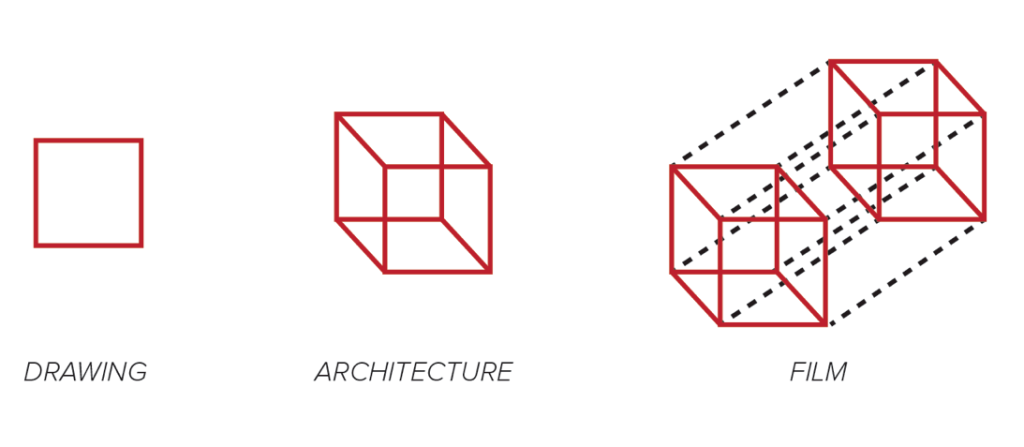

Traditional portrayals of architecture run the risk of being static and relying too much on the imagination to weave together a coherent design. Drawing is a two-dimensional practice, while architecture engages a third dimension in construction. Film practices go a step further and engross yet another dimension – time.

image by author

Still in order to experience each of these dimensional aspects, one additional dimension is needed – one that is omniscient and removed from the work and delves in a viewer’s mind. To experience a two-dimensional drawing, one must be viewing it from a third dimension. To experience architecture, one must be progressing in or around it to fully piece it together in his or her head. This concept of memory is what drives the four-dimensional practice of film. Just as a person creates a mental model of a building in one’s mind, a film viewer creates a mental timeline to piece together what he or she has just seen and what they are currently seeing – thus creating a narrative. Understanding and using this supplementary dimension of memory can create a new series of tools for an architect or designer to bring his or her idea to life and engage a larger audience than is currently being done, all through the use of a visual narrative.

While walkthroughs and fly-throughs are becoming increasingly popular in architectural presentations, they actually run the risk of hindering a design. These techniques are used merely as a visualization tool and lack something fundamental – the narrative perspective. Unnatural camera angles, abnormal movements and too smooth of a walkthrough take away from the suspension of disbelief that is important to filmmaking. The concept behind this is to make the viewer forget that they are watching a film. The audience should feel like a part of the story. Often times in ordinary filmmaking, the story arc takes precedent over the world it resides in. Architecture is not the frontrunner. Yet when architecture is moved up to the focus of the film, it supports the narrative much more to make this suspension of disbelief applicable. Audiences become engaged in the world they are submerged in, whether actual or imaginary. What happens when you take this a step further – not just using architecture to aid a narrative, but instead setting it up to be the story. Architecture should be the main actor and a narrative should be created around it in order to fully conceive a critique or design.

image by Factory Fifteen

Very few walkthroughs or fly-throughs that embody thisarchitectural narrative actually exist as of now. Any designer that can actually progress into this field has the ability to become a frontrunner and completely redefine the future of architectural visual representations. Could these frontrunners be Factory Fifteen? This group of recent architecture graduates uses film as a means of expressing critiques of the built environment. The graduates do not follow the framework of traditional architects, but are instead filmmakers who use the medium to explore the social and political impacts of works of architecture.

One of Factory Fifteen’s films, Megalomania, serves as a critique of the fast paced development of many major cities in the world today without the thought of long-term sustainability:

“Megalomania perceives the city in total construction. The built environment is explored as a labyrinth of architecture that is either unfinished, incomplete or broken. Megalomania is a response to the state of infrastructure and capital, evolving the appearance of progress into the sublime.” (Gale et al)

video by Factory Fifteen

The film asks numerous questions: how much maintenance do these cities require, what will these rapidly progressing cities look like in twenty or thirty years, and is sacrificing sustainability to advance the timeline of construction truly worth the environmental and social problems that may arise down the road? The film’s director and a founding member of Factory Fifteen, Jonathan Gale, says, “This whole idea that there’s not enough space for people is kind of a myth, the space is just being really badly used. Companies don’t want to move offices, they want a new tower. And they don’t want to move into someone else’s tower, so there’s a lot of empty office space. It’s this greedy, careless attitude” (Gale et al). Megalomania invokes an emotion into the audience by beginning and ending the narrative with a look into a human’s eyes. The entire film takes place from the perspective of this person to make the crumbling city appear completely devastating. Without this human-based architectural narrative, the critique of these hastily emerging cities would certainly be less persuasive.

Another Factory Fifteen film, Speculative Landscapes, takes this storytelling perspective a step further. The film serves as train’s journey through time. Throughout the journey, a girl’s face comes in and out of focus. Her expression seems to reflect upon the landscape that she is experiencing.

video by Factory Fifteen

It begins in the past, showing a world before architecture. It then progresses to the architecture of today, showing a landscape many can relate with. The verticality of a city skyline is stressed. The train journey continues and moves into another landscape – one showing the possibility of the future of architecture. Buildings are seen overlapping and in constant construction. Nothing remains finished. While this incomplete viewpoint may seem degenerating or disheartening to some, it actually is something to be celebrated. Construction is an art to be admired in Factory Fifteen’s work. Jonathan Gale describes this, “…There’s an honesty in parts, we don’t want to see things covered over in plasterboard, we want to see things” (Gale et al). They seem to be praising the aesthetic of having a building’s guts and internal mechanics on display – mirroring the look of buildings like the Lloyd’s Building in London or the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It’s an incredibly effective tool at looking at near futures and alternative present times.

Centre George Pompidou, Paris, France; image by Natalie Wall

Paul Nicholls is another filmmaker who uses film as a medium for architectural critique. He directed a film entitled, The Golden Age: Somewhere, to express the possibility of a “downloadable architecture” in the future.

video by Paul Nicholls

The film begins with a city skyline. Among the physical buildings, virtual skyscrapers begin to construct themselves to redefine the silhouette of the metropolis. The film then brings itself into an individual’s home, shifting the camera to be the individual’s personal perspective again reinforcing the use of narrative in architectural representations. The individual then uses a computer to bring a virtual Hyde Park into her own home. Nicholls says, “We are transported to a time where the boundaries between what is real and what is simulated are blurred. We live online and download places to relax, parks and shopping malls. The local becomes the global and the global becomes the local. It is a truly ‘glocolised’ world” (Frearson). This film is further removed from reality than Factory Fifteen’s Megalomania and Speculative Landscapes, yet still encompasses a narrative perspective to look at the “what if” of the future.

image by author

Architects have been exploring this new way of cinematographically exploring architecture for decades with increasing popularity. How can film influence architecture? Architecture surrounds us (quite literally) at all times, yet it is not groveled over in magazines like fashion, or culturally shared like music. It seems to be held on such a high, artistic pedestal that the masses believe one should be educated in architecture to discuss it. Perhaps moving into a cinematographic approach can allow it to be nonchalantly discussed the way a non-filmmaker discusses a movie he or she recently saw in theaters. It is time for this cinematic approach to design to move up from experimentation. It should now be the standard in order for the masses of humans to share, explore and dissect it.

Featured Image Source: Factory Fifteen

Sources:

Arx, Peter Von. Film + Design: Explaining, Designing with and Applying the Elementary Phenomena and Dimensions of Film in Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983. Print.

Frearson, Amy. “The Golden Age: Somewhere by Paul Nicholls.”Dezeen Magazine. N.p., 09 Mar. 2012. Web. 01 May 2015.

Gales, Jonathan, Kibwe Tavares, and Paul Nicholls. “FACTORY FIFTEEN.”FACTORY FIFTEEN. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Koeck, Richard. Cine-scapes: Cinematic Spaces in Architecture and Cities. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Schöning, Pascal, Julian Löffler, and Rubens Azevedo. Cinematic Architecture. London: Architectural Association, 2009. Print.

Schöning, Pascal. Manifesto for a Cinematic Architecture. London: AA Publications, 2006. Print.

Tawa, Michael. Agencies of the Frame: Tectonic Strategies in Cinema and Architecture. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2010. Print.

Uluoglu, Belk?s, Ayhan Ensici, and Ali Vatansever. Design and Cinema: Form Follows Film. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2006. Print.

Yee, Angela. Depth Perception Architecture and the Cinematic. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque Et Archives Canada, 2007. Print.

The best resource for anything related to Cmputer Aided Design is the CumInCAD database. (Cumulative Index of Computer Aided Architectural Design) It indexes conference proceedings and journal articles, with many of them having the full text available in the database.

A lot of what is indexed in CumInCAD is not indexed in LionSearch or Avery.

http://alias.libraries.psu.edu/ERESOURCES/PSU01451

The database is a bit clunky and lacking in the User Interface department, but it is an excellent resource.

Another issue is that you have to create a free, personal account to access the full text items.

Despite the appearance and needing to create an account, please use this source. The information in it is high quality and current.

We’ve created a brief guide on how to use CumInCAD here:

http://www.libraries.psu.edu/psul/architecture/cumincad.html

Mike:

You might also want to take a look at some of the research guides related to film that are listed here:

http://www.libraries.psu.edu/psul/researchguides/communications.html

I stumbled across this chapter in a book, while looking for something else.

Chapter: “Set and Location: the Garden and Film” by Kenneth Helphand

it is located in the following book

Book: Representing Landscape Arhitecture, ed Marc Treib Call# SB472.T728 2008

“The development and techniques behind filmmaking should be implemented regularly as a way of approaching the realm of architectural design” Which part of “the realm of the architecture design” are you referring to ? Do mean the architecture design process ? or the final product? Should this be implemented to help architects communicate their ideas to the clients? or for the architects themselves to better understand the spatial qualities of the design. You can state your thesis statement with a more focus on architecture by saying for example: “The architecture design process should manifest the filmmaking cinematographic techniques to … (state the most important reason why this should be done).”

The points you are discussing throughout are thoughtful and show an organized thinking process. “Film practices go a step further and engross yet another dimension – time.” Awesome ! I believe this is a critical and very interesting aspect that I would like you to expand more on in the rest of your paper. How can time be expressed in architectural drawings? Do we show it through vignettes? or is it expressed through the different renditions of a space according to the different scenarios it should be exemplifying?

Your thesis statement as well as your first paragraphs imply that you will be discussing how filmmaking techniques should be used in architecture. But then you state “How can architecture influence film? How can film influence architecture?” I believe these are two drastically different thesis statements. Sure, they definitely do influence each other. However, this will be very hard to discuss in a 1500 words paper. It would be best for you to focus on one question and aim at answering it, I believe this would be “How can film influence architecture” as this is what most of your writing implies.

Hi Mike,

You make some really interesting points and I see your effort in focusing more on architecture in this draft. However, there is one aspect that I have seen confusing throughout your writing which is your audience. Your audience seems like it shifts from one paragraph to the other. Sometimes I get the vibe that you’re approaching your topic to help the relationship between the architect and the client. In other instances, it seems like you are trying to approach the general public through the idea of making architecture more interesting and intriguing to be in magazines like fashion. Whichever one you would like to go with is fine. Just focus on one and make your argument revolve around it.