“Introducing Stormy Foster” Hit Comics Vol 1 #18

Edited by Jerry Iger and illustrated by Max Elkan.

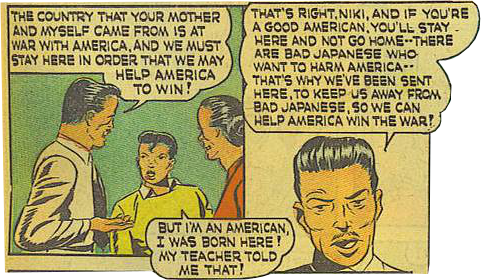

The sidekick Ah Choo comes from Quality Comics’ series Hit Comics, which ran from 1940-1950. His first appearance is in issue 18, “Introducing Stormy Foster,” as an unidentified delivery boy, but by issue 21 he is named and stars as the Great Defender’s sidekick in fighting the Germans.

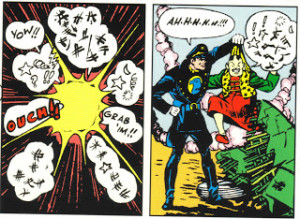

In his introduction, he switches his Rs and Ls, as the stereotype dictates, and speaks non-standard English. In issue 18, Ah Choo plays an extremely minor role and is not fully fleshed out as an archetypal sidekick until issue 21. Because of this, there’s little to comment on his appearance, other than his slanted eyes and foreign clothing. His only distinguishing characteristic is that he’s not the enemy–because he’s Chinese.

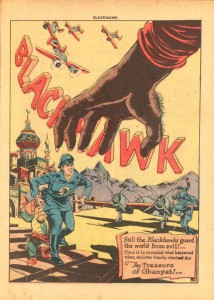

In issue 18, where Ah Choo and the Great Defender first appear, the main enemy is Oshinto Karu, “notorious Asiatic spy who has been hunted for months by the F.B.I.” Karu is Japanese, the nation’s enemy, but his group falls under the nondescript “Asiatic” group. While Karu’s name clearly marks him as Japanese, his allies are an unknown and vague Asian–only someone with knowledge of Asian cultures in the 1940s would be able to wager their ethnicity. Of course, that’s not the point of the comic. Other moments of concern come when the narrator refers to the “Oriental” enemies as “yellow assassins” and when they run from the Great Defender, “like a pack of terrified rats, the Oriental spies scamper to the roof.” Hilarious! These enemies also call their mission a suicidal mission for the great emperor. Classic.

“Introducing Stormy Foster” is very representative of 1940s American attitudes towards Asians, symbolizing just how general but lethal popular media fostered with Asian stereotypes. Ah Choo’s first appearance also reveals this othering of Asians in his speech patterns, which both are drastically changed in issue 21 as he is given more substance as a character.

“King Korman’s Castle” Hit Comics Vol 1 #21

Edited by Jerry Iger and illustrated Max Elkan

As a sidekick in issue 21, he actually helps the Great Defender with his slingshot, but obviously is not on the same level as the main superhero. While the artist Max Elkan portrays Ah Choo more positively than in the previous issue, he still is seen as the “good” Asian or the “model minority.” Moreover, the only positive change in his character is his absence of the Asian Accent. Similar to Chop Chop, Ah Choo’s appearance is heavily racially coded, with slanted eyes, buck teeth, and what might be a vague reference to “Oriental” clothing.

So, we’ve witnessed Ah Choo as a racial caricature, what now?

First, let’s talk about the effect and implications of these comics. Basically, what’s the point of bringing this up 70 years later? Theoretically, it’s in the past. We’ve changed now! Haha no! Racial caricatures have only changed in the last 70 years, as yellowface has just transformed into whitewashing. Whitewashing can be seen in the casting of white actors for established Asian characters, such as in Aloha, Exodus, Prince of Persia, Pan, Avatar: The Last Airbender…and the list goes on. This also applies for animated characters, in terms of literal whitening of their skin, such as Aladdin, or if you know anime, Robin Nico from One Piece. Asian stereotypes have survived the modern age, and they still reduce people to caricatures. While Ah Choo’s personality is similar to Robin’s regarding the sidekick archetype, his appearance is incredibly othering. Culturally he has assimilated, but he will always be foreign.

Superhero comics is not a cultural product to be taken lightly. Consumable by many, comic books pervade the popular conscious and the private conscious. Ah Choo’s inability to fully assimilate parallels the experiences of Asian Americans today and our obsession with mocking Asians only continues to belittle their existence.

“We have always worn masks. Forced to wear them by others who feared us, hated by us…Since we first set foot on these shores, made to play the part of the “forever foreigner,” the “yellow peril,” the invading, unassimilable hored…Hidden behind identical slanted eyes and geisha makeup by others’ ignorance…exotic, other, not quite human… Those old masks–imposed by others, reinforced by the weight of historical repetition–have, over time, obscured and distorted our identity.” -Jason Sperber

Jason Sperber is part of the Secret Identities crew and writes for Nerds of Color. This quote comes from Cathy J.Schlund-Vials’ article, “Drawing from Resistance,” in the Amerasia Journal. In Ah Choo, we can see its relevance, for he represents this “forever foreigner,” and considering the Asian caricatured face as a mask, we can understand its obscuring nature.

Crandall, Reed, Elkan, Max and Iger, Jerry. “Introducing Stormy Foster.” Hit Comics Vol 1 #18. Quality Comics. December 1941.

Elkan, Max and Iger, Jerry. “King Korman’s Castle.” Hit Comics Vol 1 #21. Quality Comics. April 1942.