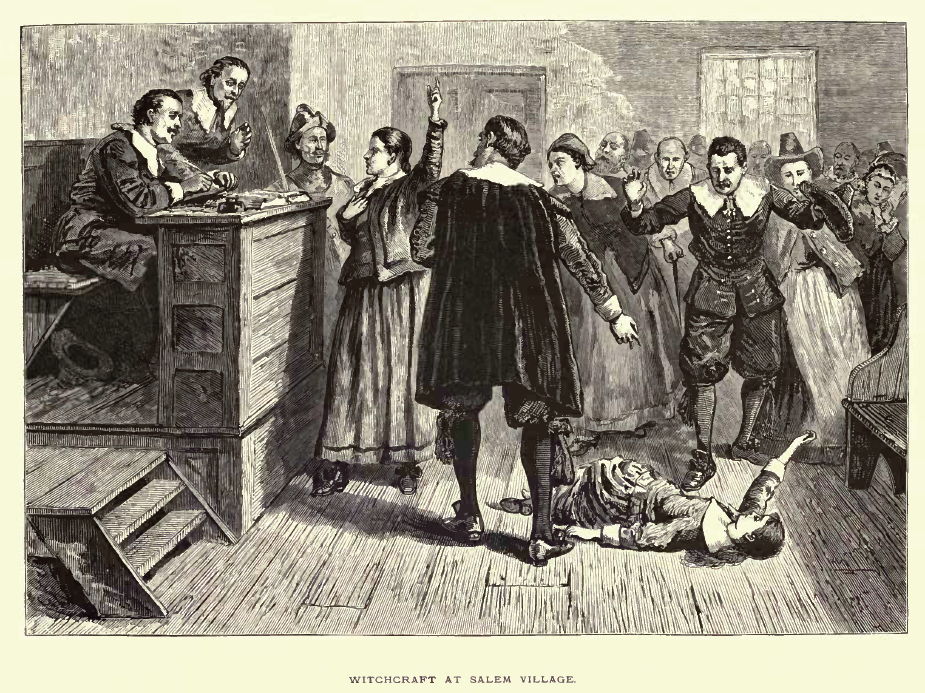

The previous statement of “the most effective strategy to convict witches” may seem quite archaic. After all we have come a long way from the Salem witch trials of 1692. How can we even compare the justice system today with it’s advent of DNA evidence to the days of superstition and witch trials? Common American folklore for the Salem witch trials offers trial by ordeal as the method to determine a person’s innocence. Trial by ordeal is essentially a test usually a torturous one to determine a person’s innocence. Many forms of these are capable of killing the accused .One of the most popular is the dunking or drowning of suspected witches.Our current justice system has eliminated quite a few of the flaws of the past, hearsay, gossip and unsupported claims are no longer admissible but were usually accepted during the 1692 Salem witch trials (UMKC, 2009). Historical evidence however, opposes the common folklore of witch dunking or trials by ordeal. In actuality, suspects of practicing witchcraft were typically prosecuted by eyewitness accounts and confessions with the majority of the convicted being hung.

See page for author (Public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

These methods of prosecution are ones that are still in practice today and unfortunately can end with results similar to trials of the past, the innocent being convicted of crimes. Cases which have been overturned with DNA evidence such as the 1984 conviction of Ronald Cotton highlight some of the inaccuracies with eyewitness evidence and the possible contamination to eyewitness accounts. The victim in the Cotton case identified Cotton as the perpetrator of the crime from a photo and live police lineup. After serving 11 years in prison, DNA evidence exonerated him and identified the actual perpetrator of the crime (Schneider, Gruman & Coutts, 2012). The victim had erred in their identification of the perpetrator. One possible cause for this is misidentification is a phenomenon known as false memories. Multiple studies have shown that people are prone to have their memories corrupted when a third or outside party introduces an incorrect detail (Stanford University, 1999). This false detail may then be incorporated into the person’s memory of an event. The person or eyewitness is most likely unaware that this phenomenon has occurred and they commit to this false memory as if it was their own. Additionally, introducing false cues or suggestive language to an eyewitness can also affect their memory causing them to add details that might have not existed. Investigators can unwittingly corrupt eyewitness accounts by simply using suggestive language in their questions, essentially leading the eyewitness down the incorrect path of false recollection.

Once these memories are created another factor may influence the eyewitness, a cognitive error known as belief perseverance. This is a tendency for people to maintain their beliefs regardless of evidence opposing their belief or memory. They may do this to the extent of discrediting or misinterpreting the opposing information. This phenomenon often affects jurors when they are presented with evidence that is later deemed inadmissible. There is a tendency for the jurors to continue to give weight to this earlier presented evidence even though they are instructed to ignore it by the court.

These causes of misinformation can greatly hinder the ability to seek the truth. Often these instances of misinformation are not deceptions generated on purpose but phenomena created by the human mind. Surveillance cameras often assist in identifying perpetrators of crimes. Recently, it has been suggested that law enforcement officers should wear video recording devices. A video record is an effective tool to help avoid some of the shortcomings in how people remember events and the ways their memories can be affected. An instructional video for prospective jurors and investigators might be prudent in making them aware of theses tendencies in an effort to reduce the effects of these phenomena. Otherwise, we may continue to convict the innocent as we have done in our past.

References

Schneider, F.W., Gruman, J.A., & Coutts, L. M. (2012). Applied social psychology; Understanding and Addressing Social and Practical Problems, (2nd Ed) Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage Publications

Stanford University. (1999). Retrieved from http://agora.stanford.edu/sjls/Issue%20One/fisher&tversky.htm

University of Missouri Kansas City. (2009). Retrieved from http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/salem.htm

Additional reference for prior post:

Day, DM & Marion, SB. (2012). Applying Social Psychology to the Criminal Justice System in Applied Social Psychology: Understanding and Addressing Social and Practical Problems (2nd ed.) F.W. Schnedier, J.A. Gruman, & L.M. Coutts (Eds.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1412976381.

Misleading postevent information (MPI) has been found to be one source of memory errors. Loftus and collegues (1978, as cited in Aronson et al., 2012) completed some novel memory experiments showing how easy it is to alter a visual memory with verbal cues injected into the memory. For example, one of the experiments contained two groups of which both were shown the same slide show of a car crash. The independent variable was the phrasing of this question: 1) “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” and 2) “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other (p. 223)?” Changing the word hit to crash created a 7 mph increase in the speed that the car was goingin the viewers, but what compounds this situation is that a week after participants watched this car crash, they were asked, “Did you see any broken glass?” The participants who heard the word smash reported 32% of the time that they had seen broken glass, but the participants hearing hit reported seeing glass only 14% of the time. There was no broken glass in the original car accident slide show the participants watched (Aronson, et al., 2012, p. 223).

This ability for words to prime and reshape our memories is easily demonstratable. Deese (1959, as cited in Bruce & Winograd, 1998) demonstrated the ease that words can reshape memories through experiments utilizing sequences of words that represented ordinary common schemas, e.g. desk, pens, papers, stapler, chair. However, a word like chair if actually left out from this sequence will often be recalled with a memory of it being in the original list of words. This is a result of the list priming for a schema that chair is easisly associated with. In this example from Luftus, the word crash hints at speeding and triggers the image of broken glass. Whereas, hit is something more softer. Sometimes it is used metaphorically for more friendlier things like a tap to your friend’s arm when joking around. These awarenesses have led to the use of the cognitive interview (CI) that has been found to increase the accuracy of witnesses’ recall from 20-50% (Fisher, 2010, as cited in Day & Marion, 2012) and much of this shift in a more productive interview technique came from the work of applied social pscychologists like Elizabeth Loftus, Gary Wells, and their collegues (pp. 256-257).

References

Aronson, E., Wilson, T.D., & Akert, R.M. (2010). Social Psychology. Seventh Edition. Prentice Hall. ISBN 10: 0-13-814478-8.

Bruce, D. & Winograd, E. (1998). Remembering Deese’s 1959 articles: The Zeitgeist, the sociology of science, and false memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 1998,5 (4), 615-624. Retrieved from http://download-v2.springer.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/static/pdf/175/art%253A10.3758%252FBF03208838.pdf?token2=exp=1428212782~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F175%2Fart%25253A10.3758%25252FBF03208838.pdf*~hmac=44d45aaa3954c2b68de2741fc5a9a696be409cf75a923be20db7e530133df8e0.