[Pictured above] is a “Bobo Doll” used in Albert Bandura’s experiment. Findings from the study revealed evidence that supported his Observational Learning Theory.

Violent acts have spread like wild fire throughout the course of history. Why do negligent acts keep reoccurring? No one knows the sole reason why one person performs deceitful behavior, while another person does not. Researchers have proposed several theories which explore the relationship between the brain and violent behavior, as well as other aspects that may trigger violence. For instance, is delinquency contagious through exposure (personal or media-coverage)? Some individuals suggest that crime is the result of protecting oneself or people they care about. However, others insinuate that coercive behavior is acted out by revenge-seeking behavior to punish others. Another theory investigates whether certain types of brains are more susceptible to violence or aggression than others. Rowell Heusmann is a psychology from the University of Michigan who proposed that, “If you’re exposed to violence, you’re more likely to catch it (Swanson, 2015).” Accordingly, this statement relates to Albert Bandura’s Observational Theory, also known as Social Learning Theory – SLT (1970). The lesson commentary defines SLT as, “watching someone else perform a behavior, then the observer performs a similar behavior in a similar situation (L.5 Commentary).” The report focuses on the observational theory relative to a clinical/counseling aspect of psychological practices. Is violence typically learned by observing and imitating actions we see around us? Moreover, does exposure to violence spark individuals to execute savagery themselves?

A gloomy shade of darkness asphyxiates the victims who have stared fear in the face at some point in their lives. Words cannot describe the victimizing terror that preys on the lives of innocent people. Violent trepidation spreads like an infectious disease into the minds of certain disturbed beings. Why are some people susceptible to violent manipulation, whereas others cease and refrain from any type of hostility? The Washington Post published an article called, “Why Violence is So Contagious” which highlights key aspects for condoning violent behavior (Swanson, 2015). Ana Swanson proposes that exposure to violence has been significantly increasing throughout the years. Conclusively, frequent revelations of violent behavior may be imitated by certain individuals (Swanson, 2015). Furthermore, the Social Learning Theory illustrates why people imitate the actions they see around them.

The observational theory describes the way that people imitate certain behaviors (such as violence) is through a process known as, modeling. An article by the British Journal of Psychology defines modeling as, “learning by watching, interpreting, and evaluating peers carrying out a task (Swanson, 2015).” Additionally, effective modeling follows four stages described as: “observation/attention, emulation/retention, self-control/motor reproduction, and motivation/opportunity/self-regulation (Lesson 5 Commentary).” The British Journal of Psychiatry (2015) revealed that initially, the learner actually observes the behavior and relevant elements in the learning environment while it is in action. Second, an individual internalizes the skill by storing the learned series of steps in their memory, so they can remember or reference them later. Next, the learner must have the motor-skills required to mimic the behavior. Finally, they exhibit necessary talents and are provided with an opportunity to engage in the behavior (Swanson, 2015). As a result, the learner converts their mental representation into a physical task. Observing and imitating violent behavior is the most prevalent in the first, and potentially second steps of the modeling process. For instance, hopefully it would not be in anyone’s mind set to follow all of these steps until the end while carrying out an act of violence. Relatively, modeling is related to violent behavior because it drives learned mimicry of the observed behavior from the surrounding environment.

Why do people pick up violent behaviors? Albert Bandura (1970) developed the observational theory, in which the brain adopts violent behavior mostly by instinctual processes. Bandura conducted a study, called the “Bobo Doll Experiment,” in order to assess the validity of this causal relationship. His study consisted of two groups of kids who observed an adult playing with the inflatable “Bobo Doll” under two different conditions. The first group analyzed an adult engaging in aggressive play where they hit and kicked the doll several times. However, the second group viewed the adult calmly and nicely play with the doll. After observing the adults, the children played with the Bobo doll themselves. The results displayed that the first group (observed aggressive play) were much more inclined to behave violently when they played with the toy. Nonetheless, the second group mimicked playtime by engaging with the doll in a peaceful and friendly manner. The article mentions, “the effect was stronger when the adult was of the same sex as the child, suggesting that kids were more likely to imitate people they identify with (Swanson, 2015).” These findings concluded that people learn through imitating observed behavior. Furthermore, the “Bobo Doll” experiment incited future research related to the social learning theory. The article states, “Decades later, scientists began to discover just how much our brains are wired to imitate the actions we see around us – evidence suggesting that human behavior is less guided by rational behavior than people believed (Swanson, 2015).” Conclusively, much of our behavior is caused by automatic instincts which mimic foreseen actions.

Additionally, findings from the Bobo Doll experiment intrigued a group of Italian researchers (1990), in which they utilized findings from the previous study to test their own theories about the observational theory’s relativity to neurological processing. In their experiment, they investigated that parallel sets of “mirror neurons” were released in both of the following situations – while a monkey grasped an object and while observing another primate gripping the same object. Firing of these analogous neurons is prevalent in both primates and humans. This neural activity takes place in the premotor cortex, which is the brain region liable for “planning and executing actions (Swanson, 2015).” Additionally, the premotor cortex is essential for learning things through imitation, including violent behaviors. Neurons stimulate the premotor cortex If we are exposed to direct observation of someone acting violently. When this brain region is activated, we feel like we are the ones actually doing the victimizing behavior. Marco Iacoboni, a psychiatric professor, concluded that “these ‘mirror neurons’ (and activation of the premotor cortex) may be the biological mechanism by which violence spreads from one person to another (Swanson, 2015).” The first thesis statement asks if violence is typically learned by observing and imitating actions we see around us? Absolutely! Albert Bandura’s observational theory (1970) explains that violent behavior is learned through exposure and imitation of an observed act of violence. The study gave heart to the well-known expression: * Monkey SEE, Monkey DO!! *

Accordingly, the second half of my thesis statement asks if exposing people to violence prepares them to commit violent acts themselves. For instance, is hostility increased when exposed to gruesome video games, television shows, or news? In other words, does the prevalence of violence in the media expose us to heightened levels of aggressive behavior? When individuals experience brutality through media programs or video games, they are more than likely not going to go out and commit violent acts themselves. Although, after continuous exposure they may begin to adapt to these terroristic occurrences. Alternatively, they may start to become numb to some of the gruesome imagery that they used to be completely appalled by. For instance, the article compares these feelings to those fighting in war typically grow less disturbed by blood and violence (Swanson, 2015). Overall, continual exposure to violence on personal real-life accounts, or through the media, is related to increased aggression.

Hostile attribution bias means to interpret other’s actions as threatening or aggressive. This bias may be influenced by violent media, or by repulsive actions including rejection, teasing, yelling, or belittling (Swanson, 2015). Being subjected to cruel media makes people react in a more aggressive manner, as well as an increased likelihood to imitate revenge-seeking behavior.

Furthermore, the next objective will focus on the most effective way to prevent violent behavior from spreading. For instance, in order to dispel acts of aggression, it is critical to limit the amount of exposure to violence that someone experiences. Enforcing restrictions on the amount of violent media that is allowed to be published will make people not as inclined to negatively react or imitate violent behavior, compared to if they continued to regularly observe negative accounts of terror. Incidences of corruption should not be seen as a normally occurring phenomena. If a violent occasion is not relevant to the endangerment of people’s lives to a major degree, then it should be evaluated with stricter guidelines. Evaluations will consider whether it is necessary to expose the news story to a significantly large audience, as well as consider how the audience members will respond to the situation (become more aggressive, lash out in a violent manner, become terrified or sad, etc.) Majority of the time, violent media would be better left unsaid in order to protect the well-being of its viewers. It is critical that we stop prompting the spread of violent news stories, because many people learn and imitate various behaviors (whether minor or extreme) that they learned primarily from media sources. Limiting exposure to violence is one of the most effective ways to stop spreading around volatile behavior like an infectious disease. In conclusion, acts of negligence keep on reoccurring since the human brain is wired to learn things (such as violent behavior) through imitating actions that we see around us.

In conclusion, violence is a dark and fearful topic to discuss. The outbreak of terroristic outrage is quickly spreading through patterns of acquired aggression and hostility. Heightened levels of exposure to violence trigger it to spread at an increasing rate throughout the world. Evidently, the most effective way to diminish or slow down spread of violence and terrorism is to get rid of cruel and unnecessary news stories, as well as limit exposure to violence.

Conclusively, Albert Bandura’s observational theory (1970) constitutes that violent behavior is learned through imitating observed behaviors that we notice in our surrounding environment. Bandura connected our brain activity to instinctual responses to the observed actions surrounding us. A group of Italian researchers (1990) performed a study on how a monkey responded to grabbing an object himself, or analyzing what happened to the monkey when he watched another primate grasp the same object. Results of the study implicated that the area of the brain responsible for ‘planning and executing actions’ (premotor cortex) is stimulated by a parallel set of ‘mirror neurons.’ These neurons are released when we observe someone acting out in a violent manner, and we imagine ourselves performing the violent action ourselves. Dr. Marco Iacoboni (1990) formed one of the most valuable conclusions of this report, “these neurons may be the biological mechanism by which violence spreads from one person to another (Swanson, 2015).” Modeling threatening behavior typically results from high exposure rates to the media. Likewise, mimicking such behavior causes amplified levels of aggression and rage, which may impair an individuals’ ability to plan and execute actions appropriately. In conclusion, humans will follow the four steps of effective modeling proposed in Albert Bandura’s observational theory (1970) in order to learn various things through imitation (such as violent behaviors) and observation of a behavior in which they learn to mimic themselves.

References:

Swanson, A. S. A. (2015, December 15). Why violence is so contagious. Washington Post. Retrieved online from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/12/15/why-violence-is-so-contagious/?utm_term=.fb549a29f126

Pennsylvania State University (n.d.). Lesson 5 Commentary. Retrieved online at https://psu.instructure.com/courses/1834710/modules/items/2173666

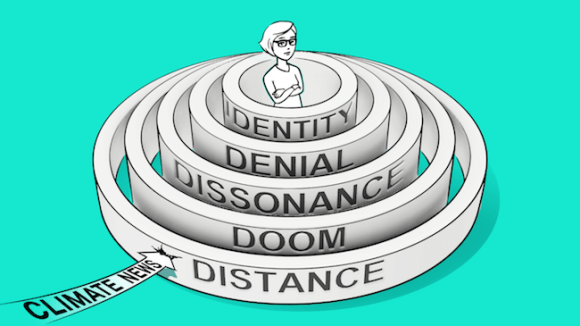

The idea of trickle-down environmentalism is as alluring as it is flawed, mimicking the deficiencies of its economic predecessor. Well-intentioned proponents of the idea suggest if the elite embrace sustainability, their behaviors will set an example that trickles down to the rest of society, leading to widespread environmental action. However, this idea falls short of addressing the complexities intrinsic to the social dilemmas facing society in the fight to save our planet.

The idea of trickle-down environmentalism is as alluring as it is flawed, mimicking the deficiencies of its economic predecessor. Well-intentioned proponents of the idea suggest if the elite embrace sustainability, their behaviors will set an example that trickles down to the rest of society, leading to widespread environmental action. However, this idea falls short of addressing the complexities intrinsic to the social dilemmas facing society in the fight to save our planet.