Major Spoilers ahead obviously

Most people who see this won’t have watched this movie, but after this blog, I really hope you do.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1QSs8WHaZE

If you’re really cool, you’ll follow along with my timestamps to find the scenes. Are you that cool?

Introduction

Koe no Katachi is a 2016 anime movie made by Kyoto Animation (KyoAni) and directed by Naoko Yamada, an excellent director that has been a part of many KyoAni works. The synopsis:

As a wild youth, elementary school student Shouya Ishida sought to beat boredom in the cruelest ways. When the deaf Shouko Nishimiya transfers into his class, Shouya and the rest of his class thoughtlessly bully her for fun. However, when her mother notifies the school, he is singled out and blamed for everything done to her. With Shouko transferring out of the school, Shouya is left at the mercy of his classmates. He is heartlessly ostracized all throughout elementary and middle school, while teachers turn a blind eye.

Now in his third year of high school, Shouya is still plagued by his wrongdoings as a young boy. Sincerely regretting his past actions, he sets out on a journey of redemption: to meet Shouko once more and make amends.

Koe no Katachi tells the heartwarming tale of Shouya’s reunion with Shouko and his honest attempts to redeem himself, all while being continually haunted by the shadows of his past.

It’s a story of redemption, forgiveness, and learning to love yourself, themes that should be handled carefully. Yamada does a great job of directing not just how the characters should be portrayed visually, but aurally as well, using Kensuke Ushio’s soundtrack to the fullest extent. For this blog post we will focus almost solely on Shouya Ishida (the bully) and Shouko Nishimiya (the victim), as it is what this movie really revolves around. It really digs deep into the effects of school bullying on the victim and the bully, years down the line. It’s the first blog post where I’ll put my balls on the line and actually analyze the movie for myself. Let’s go.

Sight – the shot composition

The Walk

There are three long scenes in A Silent Voice where Shouya walks down a hallway. A very mundane thing. But how he walks down the hallway, and the way his stride is pictured, tells the entire story, and shows his entire arc of character development throughout the story.

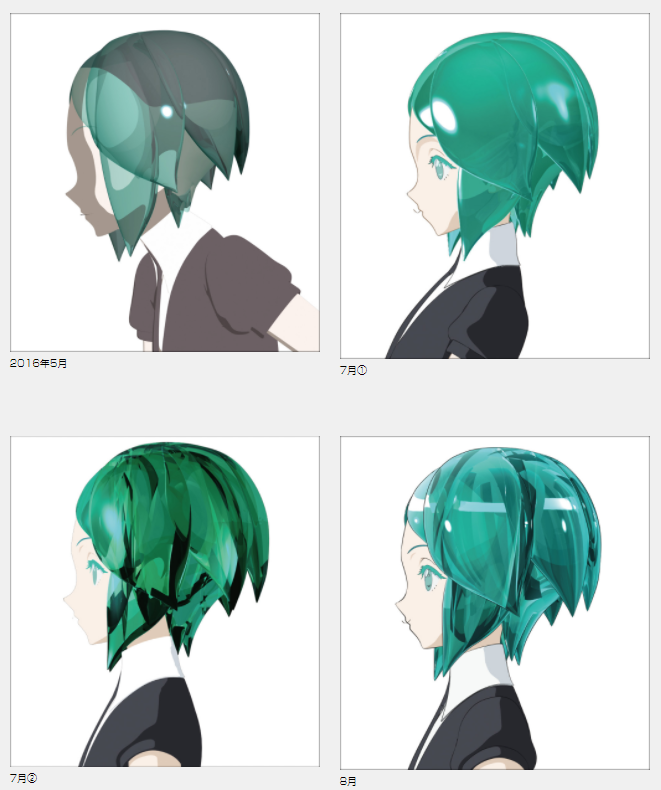

The first walk comes in a flashback to Shouya’s elementary school days, before Shouko entered the school. At around 0:03:00, we see Shouya striding through the elementary school like a cocky little bitch. He is a cocky little bitch. He swings his arms confidently, always slightly in front of his two friends, indicating that he’s probably the leader. He is, by the way.

The shot in question shows Shouya’s bust, focusing directly on his smiling face in a sea of other faces – a sea of faces that can still be identified, a fact that will become very relevant in the next hallway walk.

A few seconds later we see Shouya waving to all of his friends – Kawai, Ueno, Shimada, Hirose (left to right). Again, it’s the same exact style of shot, and this time we can see that everyone’s eyes are on him, indicating that he is pretty much the alpha male dude. The song played during this scene is “My Generation” by The Who, which I’ll talk about later.

The next scene is one of the more powerful scenes in the movie in my opinion. It takes place at around 0:29:56. It starts off from Ishida’s POV, as if you the viewer are him – more importantly, the sightline is downwards, as Shouya is looking down at the ground. You can see the legs of other students, with Shouya following around another guy so that you can only see his butt down – the camera also flashes towards Shouya’s eyes and then back to the ground, indicating that Shouya still can’t keep his head up. The camera is still focused on Shouya, but now everyone around him is blurry and impossible to make out.

And at the end of the sequence, blue X’s appear on other people’s faces, and Shouya puts his hands over his ears, blocking the entirety of the world out as he refuses to even consider interacting with his classmates. At the end there’s a relatively wide shot that shows all of the X’s on the faces, compounding the idea that Shouya is truly alone. No eye contact, no listening. Extremely coincidentally, the soundtrack played during this scene is somber, a muffled version of “Black and White”.

Now, with all of this in mind, through his interactions with other characters and Shouko, he changes, caught in parallel with the other scenes. Watch for yourself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eMB1HZhxv7A

And last we have the ending scene of this entire 130 minute movie. It’s perhaps a scene that’s controversial. Some consider this ending “too easy” for Shouya, but I disagree – Shouya doesn’t gain redemption nor an immediate group of friends, but instead the ability to look people in the face and listen to their voices.

At the beginning of the scene at the festival, you can only hear the soft piano music, but as soon as he lifts his hands from his ears, he can finally hear the world around him. Additionally, none of the “look downward” shots were used in this scene – instead it focuses on his wonder as he finally takes in the worlds of other people. Again at the end, there is an even wider shot than the previous “walk” scene, where the viewer can now take in all of the movement and conversations around Shouya.

At the very end, you can see the screen go dark save for a very bright spot in the center, Shouya’s light at the end of the tunnel. He sees the group of people he has come to accept, and the screen then does a vignette-like fade to a pastel, calming blue.

Body Language

For a deaf person, their body literally forms their language. But for many others, body language still forms most of the communicative cues during a conversation. It’s pretty common as far as I know in KyoAni anime for a conversation to change shots to the character’s legs, showing how they move around each other as an alternative to flapping lips. Not only does it save money by omitting the face, it also shows that there are other things that the characters need to pay attention to – for example, the way that Ueno moves around Shouya is pretty indicative of her crush. By centering a shot around body language, it can focus the viewer on the intended scene.

In fact, there’s a whole entire scene that does not include the two talking characters – instead, it’s directed only at their lower bodies – but it manages to convey what needs to be said between the two.

Fireworks and Falls

Fireworks are used twice in Koe no Katachi in relation to suicide, once just before Shouya is considering committing suicide, and another just before Shouko attempts suicide.

Fireworks are a reminder of how ephemeral things can be – the brilliant spark and then the subsequent darkness is a visual reminder of the Japanese idea of mono no aware, which I’ve talked about previously with regards to sakura blossoms. Here, the imagery is used just before two suicide attempts, signalling their despair towards life. But just as the firework might die out, its spark should be appreciated and everyone hopes that the firework show never ends.

Left and Right

What is the same about all of these shots? Shouya is depicted on the left of the screen, even though the person he is talking to is off screen further to the left. A typical director might place both of the characters on screen, with Shouya more logically being on the right, but instead Yamada cuts out the other person and places Shouya on the left. It’s an uncomfortable sort of scene – the empty space on Shouya’s left is unsettling on a fundamental level for the viewer.

Now where do these sorts of shots appear? In the first two, Shouya is hanging out with Nagatsuka, a kid who has suddenly proclaimed Shouya to be his one and only friend. Shouya, who hasn’t had a friend in years, is clearly unsure of first, what friendship even means and if he can call Nagatsuka his friend (a huge theme throughout the manga especially), and second, what he’s supposed to be doing during his time with him. It’s an amazing depiction of social anxiety that’s pretty subtle and doesn’t distract from the scene. In the third, his mom has just asked him why he attempted suicide, which would make any teenager uncomfortable.

Framing

This is a pretty well known shot in Koe no Katachi, and just shows off Yamada’s intense focus on her shot composition. Just look at how many goddamn red bars Shouko is trapped in, as if she’s in a prison. If that wasn’t enough, a thin tree in the foreground separates her and Ueno as they talk. It’s a common technique utilized by many directors, but I thought I’d just point out this shot. It’s great.

Flower Language

I’ve talked about flower language before, but this person did it better.

The Flower Language of A Silent Voice, Part 1: Fireworks and Daisies

The Flower Language of A Silent Voice Part 2: Marigolds and Miscellany

The Flower Language of A Silent Voice Part 3: Cherry blossoms and the transient nature of all things

It’s super well written and gives you even more insight on how Naoko Yamada directed this movie so well.

Auditory

My Generation – The Who

The opening scene, The song “My Generation” by “The Who”, which funnily enough, is said to “capture the angst of a teenager”. It is the essence of youthful rebellion , notably featuring the lyrics “I hope I die before I get old.” Additionally the upbeat music really fits the scenes shown, with everything feeling happy. Not coincidentally, the happy music ends as soon as Shouko enters the room, signalling the beginning of trouble. The director Naoko Yamada specifically picked this song out, saying in an interview with Picturehouse Cinemas:

We just wanted to have one song that everyone could relate to. The music has to be evergreen and we wanted everyone to recognise it. This is the story of Shoya and when he was at junior school he felt he was invincible but he was bored and frustrated. What better song to show both what he is and who he is?

The Song in the Piano

Kensuke Ushio considered both musical and non-musical parts very important, as sound has crucial meaning in this show. This song, lvs, plays while Shouko is being isolated by the rest of her classmates. The trick? It was recorded literally inside of a piano – Ushio disassembled a piano and set up a microphone inside – giving the impression that the listener is surrounded completely by sound – which if you think about it, is exactly Shouko’s situation – she knows that people are talking around her, but she can’t speak properly herself, and all of the sounds are muffled and unintelligible. She can feel the vibrations of the noises around her, just as we can hear the vibrations of the piano working its magic.

In the soundtrack inv, which I will talk about next, Kensuke Ushio used all of the ambient sound surrounding the piano – the hammers that make the note, the dampers that cease the vibration, and even the practice pedal of the piano.

The Sound of Silence

Koe no Katachi is about communication and the absence of communication. Shouko, being deaf and essentially mute, cannot communicate properly, which creates much of the conflict in the show. In fact, the manga it was adapted from actually benefited from the lack of sound in the manga medium, because it helped the reader empathize with the inability to hear anything. The frustration with not being able to get your feelings across is evident and the soundtrack supplements this well by using periods of silence. Well, I say silence, but it’s not exactly that. The movie uses silence, with the occasional single piano note.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QioI-lBRSJE

It’s played multiple times throughout the movie – the uncomfortable space between each note is absolutely vital to the presentation of Shouko’s deafness, and helps compound the fact that, yes, no one can speak properly to each other. It appears when Shouko introduces herself in grade school, just before Shouko and Shouya have a catfight, and several other scenes.

It’s most prevalent in the bullying scenes, which if your stomach is feeling up to it, can be found here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC1zQ-VgIcs

Conclusion

I will go back to add more things I notice in this film, I’m only ending it here cause it’s late. I hope for the people who have watched it that this enhanced your experience and for the people who didn’t that it encourages you to watch it, even with the massive spoilers. There’s so many more facets of the movie that I neglected to explore, and even more things if you read the manga.

Thanks for reading my blog for the past semester!

More Material

Wow ur cool and u want to learn more? Well there’s more well spoken people than me out there.