Hey y’all,

Here’s the link to my elevator pitch: https://psu.voicethread.com/share/25180443/

See you next week!

~Asim~

Hey y’all,

Here’s the link to my elevator pitch: https://psu.voicethread.com/share/25180443/

See you next week!

~Asim~

In reviewing my speech and comparing it to some others that I saw, it’s clear there are certain things I did really well as well as a lot of things I can still work on.

Strengths:

Weaknesses:

Overall, I’m happy that I got the speech recorded and submitted, but I will remember for the future that it takes more time commitment to do the best work I can.

~Asim

Essay Draft:

Johnny and Lisa were friends and liked to share their toys with each other, but one day Johnny got selfish and decided to take all of Lisa’s toys as his own. Some time passed, and Johnny decided to give Lisa her toys back, but he still got to use them whenever he wanted whether she liked it or not. Even more time has passed now, and Johnny claims to have given them back, but Lisa is still wondering whether her toys will ever truly be her own. This situation presents the same moral issues as the relationship between Europe and Africa. From the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade that continued through colonization in the 19th and 20th centuries, to the well-hidden ploy of Neo-Colonialism that exists today, African resources have been exploited by Western nations throughout history.

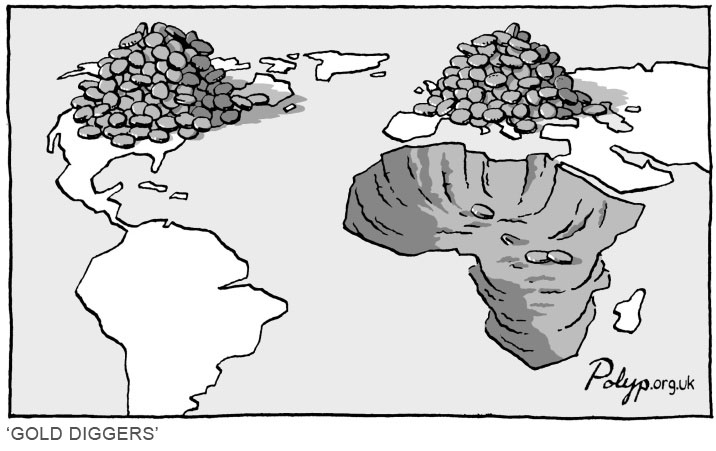

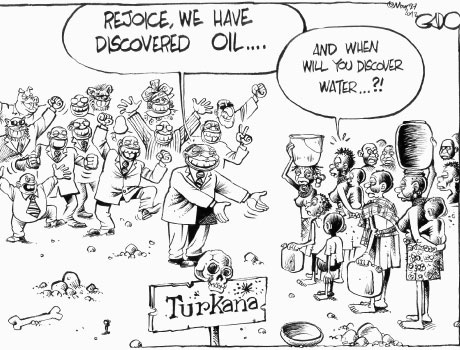

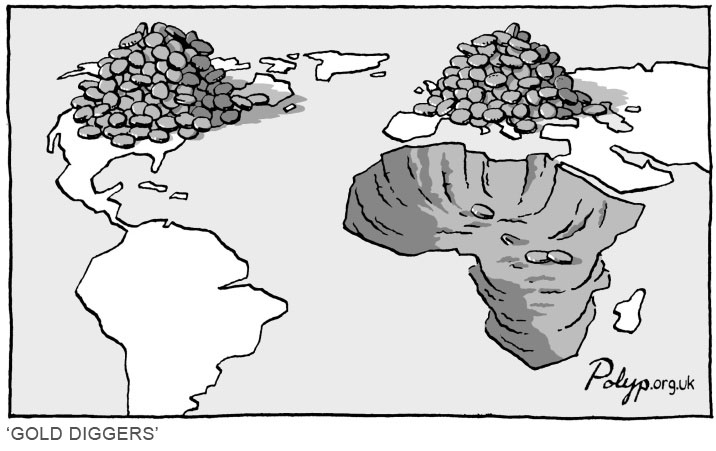

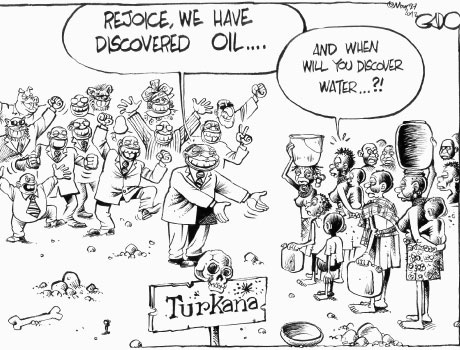

There are two civic artifacts that do a great job of addressing this issue. One, titled “Gold diggers” depicts how the material resources from Africa (gold, oil, cacao, fish, rare minerals, etc.) end up piled on the continents of North America and Europe. The other, which I’ll refer to as “The Resource Curse” illustrates the relationship between Western corporations and African people, where the Westerners “rejoice” over finding oil in Turkana, Kenya, but the citizens of the Turkana tribe are more concerned simply with finding clean water. I will use strategies of Ideological criticism, unpacking the commonplaces apparent in the artifacts, and the misrepresentation of progress in global media to examine this issue. Ultimately, both artifacts use visual rhetoric to communicate our civic duty to learn about neo-colonialism and attack the ongoing exploitation of Africa. If we address African exploitation carefully and collaboratively, we can work as a global community to repatriate the wealth of Africa, finally giving Lisa her toys back.

The rhetorical situation behind “Gold Diggers” is that most of Africa’s resources, worth trillions of dollars, still end up being exported to wealthy nations all over Europe, Asia, and North America, while many African people experience extreme poverty, hunger, limited access to clean water, and governmental corruption. This exploitation of African resources goes back to the 15th century, when the Portuguese began trading with West African merchants for gold and other commodities, including human captives. The ideological criticism in “Gold Diggers” here is the impact of this exploitation. As shown in the image, the gold from Africa physically ended up on the continents of Europe and, subsequently, America as well. Due to this, Africa is left barren, with only a little gold left. Though this civic artifact doesn’t depict any human individuals, you can see from looking at it the inequalities that have been created between the continents.

“The Resource Curse” also employs heavy ideological criticism in its visual rhetoric. In the image, the Europeans are all making expressions of joy and excitement, with heightened poses and wide cartoony smiles, while the Africans stand straight-faced and unenthused. This presents the ideology that the Westerners are more concerned with the monetary implication of new resources than the Africans’ plight. The physical difference between the thick and full-bodied Westerners and the thin, exasperated-looking Africans also suggests a gap in access to nutrition, another ideological criticism to the rhetorical situation. More visual commentary is found in the depiction of a few westerners who aren’t humanoid, like the pig-person and other people with animal heads to the left. This represents the animalistic greed of those who try to exploit others’ resources. The text, reading “Rejoice, we have discovered oil”, in which an African woman responds, “And when will you discover water…?” shows the misalignment between the two peoples’ values, which, similarly to “Gold Diggers”, emphasizes the inequality that lies between the two groups of people.

“Gold Diggers” also plays on a few commonplaces that we in the western world take for granted. One such commonplace is the association of Africa as a country and not as a continent full of nations. I vividly recall a moment in my childhood where our social studies teacher had to inform us that Africa was in fact a continent, just like Europe, Asia, or North America. Since the artifact has the entire continent voided out, it plays on our comfortability with grouping it all together, even though gold only comes from select places. It also uses the western commonplace that money=power. If the coins in the artifact represent gold, or currency, then the entirety of African resources adopt Western monetary value. It’s not just gold that gets exported from Africa, but also other rare minerals, oil, gas, cacao, coffee, raw food products, and much else. All these things were given monetary value by the Western world to trade them. Since it all ends up in the west, they have the monetary power in this situation.

The commonplace found in “The Resource Curse” is a very common and damaging one. It’s very likely that everyone who grew up in America has heard the phrase “There are starving children in Africa” before. This commonplace is especially harmful, not only because it’s not entirely true, but also because it teaches us to be comfortable with this fact rather than trying to do something about it. If we just take “there are starving children in Africa” as an unconditional truth, we will never stop and think about why this may be. The truth would connect back to the rhetorical situation of “Gold Diggers” and the exploitation of African resources, but since the Western world doesn’t benefit from a common knowledge of that inequity, it’s never a part of our education to learn about it. If the narrative was changed from “starving children” to “African people don’t have control over their own resources”, then maybe there would be more global effort for change.

A final lens that can be used to analyze both artifacts is the misrepresentation of progress in global media. Investigative journalist Tom Burgis claims in his book The Looting Machine that Africa is: “the continent that is at once the world’s poorest and, arguably, its richest” (CNN). In terms of monetary value of resources, no continent has Africa beat, and yet many countries in Africa have some of the highest poverty rates in the world. One aspect of the rhetorical situation that neither artifact touches on is the corruption present in certain governments of Africa. According to a survey by Transparency International, people in countries like South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria reported increased corruption in 2015 (Transparency.org). This is important in analysis of the two civic artifacts, as the governmental corruption is directly tied to the exploitation of political power and resources that the Europeans left behind in Africa, as depicted in the artifacts. “Gold Diggers” depicts the economic results of colonial exploitation, and “The Resource Curse” shows the ways in which neo-colonialism still plagues the African people. All of this is misrepresented in the media because the Western world is taught that colonialism is long dead and gone.

The exploitation of African resources addresses the SDGs of reduced inequalities, no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, decent work/economic growth, and peace, justice, and strong institutions. The civic artifacts “Gold Diggers” and “The Resource Curse” use many different rhetorical methods of communicating the issue at hand, but there is still much of the rhetorical situation that they are unable to cover. As civic artifacts, they are educating us so that we may gain a better understanding of the issue and possibly make more efforts to address it. The less we think about it as an African problem and rather as a global problem, we can work towards restoring wealth and resources to the people of Africa.

Resource curse:

Transparency International 2015

https://www.transparency.org/en/gcb/africa/africa-9th-edition

CNN 2018

https://www.cnn.com/2016/04/18/africa/looting-machine-tom-burgis-africa/index.html

Speech Outline:

Ideological criticism:

Commonplaces:

Misrepresentation of progress:

SDG’s:

That’s it!

~Asim

Johnny and Lisa were friends and liked to share their toys with each other, but one day Johnny got selfish and decided to take all of Lisa’s toys as his own. Some time passed, and Johnny decided to give Lisa her toys back, but he still got to use them whenever he wanted whether she liked it or not. Even more time has passed now, and Johnny claims to have given them back, but Lisa is still wondering whether her toys will ever truly be her own.

This situation presents the same moral issues as the relationship between Europe and Africa.

From the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade that continued through colonization in the 19th and 20th centuries, to the well-hidden ploy of Neo-Colonialism that exists today, African resources have been exploited by Western and Eastern nations throughout history. In this essay, I will explore two civic artifacts. One, titled “Gold diggers” depicts how the material resources from Africa (gold, oil, cacao, fish, rare minerals, etc.) end up piled on the continents of North America and Europe. The other, which I’ll refer to as “The Resource Curse” illustrates the relationship between Western corporations and African people, where the Westerners “rejoice” over finding oil in Turkana, Kenya, but the citizens of the Turkana tribe are more concerned simply with finding clean water.

I will examine this issue through the lenses of Ideological criticism, the commonplace of “There are starving children in Africa”, and the misrepresentation of progress in global media. The exploitation of African resources addresses the SDGs of reduced inequalities, no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, decent work and economic growth, and peace, justice, and strong institutions. If we address this issue carefully and collaboratively, we can work as a global community to repatriate the wealth of Africa, finally giving Lucy her toys back.

~Asim~

I chose to write on Anna Xu’s elevator pitch about The Turning Point by Steve Cutts because of the creativity of the subject matter and the execution of the pitch. I’ll go through all 5 canons in an analysis of her elevator pitch.

Invention: Anna’s choice of using this short film as her civic artifact is very admirable to me, partially because I really enjoyed watching it, but also because it demands good descriptive imagery in her elevator pitch since she can’t actually show the video. Connecting the film’s meaning to the commonplace of “species” is also a great idea, because it allows for stylistic choices like her opener and the closing question. Overall, the invention of this pitch was excellent.

Arrangement: The order of ideas is also well crafted. The hook at the beginning challenges our dissociation between “us” (humans) and “species” (animals) and presents the film’s main idea that “humans ARE animals, a species that live on Earth just like any other animal.” The next description of the video has great imagery and her live presentation got me to understand the video without watching it. She then goes into an analysis of the commonplace and closes with a provocative question about humans going extinct.

Style: I think that someone said in class that her style was both conversational and formal, and I agree that the balance was great. She gets the important points across in a concrete manner, while also adding some pathos “fluff” that makes the audience think about and feel for the animals we are killing.

Memory: Anna did a good job of using her notes to deliver an extemporaneous speech. She had to look down at her notes before each topic, but only needed a quick glance each time, allowing her to make strong eye contact with the audience. She clearly had a strong understanding and familiarity with the subject matter.

Delivery: The delivery of this pitch was one of its strongest features. Anna spoke with clear language and minimal hesitation between sentences, and I don’t remember hearing her say “like” or “um” to find her thoughts. Her pacing was strong as well, as the pitch didn’t feel like it dragged on but it did enough substantial information for me to understand her proposal.

Overall, this was my favorite pitch from Tuesday (though they were all strong). If you see this Anna, great job!

-Asim

Restoring Stolen Resources to the Nigerian City of Benin.

You may have heard of the Benin Bronzes, royal artifacts from the Benin Kingdom (now a part of Nigeria) that were looted by the British in 1897 when the Kingdom was conquered by the British Empire. These artifacts have become a symbol of many nations’ commitment to returning stolen treasures to their rightful home. The majority of the bronzes (over 900 to be specific) are currently being held in the British Museum, though the current Oba (king) of Benin City has been in contact with the museum for over a decade about getting the works repatriated to their cultural home. Efforts are finally being made to return the treasures, but the deed hasn’t officially been done yet.

The Benin Bronzes are civic artifacts because of their connotation to the ideological ethics of property and ownership. If the rhetorical situation is reducing inequalities among nations, is it ethical for one country to be in posession of another’s national treasures? While the bronzes may not hold significant monetary value, the civic issue here is the principle of returning things that have been stolen. The two lenses I will use to look at this problem are the cultural significance of these specific artifacts to the Kingdom of Benin, and the much wider viewpoint of the numerous African resources that still remain primarily in the hands of Europeans. From the 1961 murder of Patrice Lamumba in the Congo, to the Rwandan genocide in 1994, there are many wounds left on African governments and economies by colonialism and neo-colonialism. When the broader lens of these exploited resources is raised, this issue not only addresses reduced inequalities, but also the SDG’s of no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, decent work and economic growth, and peace, justice, and strong institutions.

What do you think about the Benin Bronzes being in the British Museum? Does it have a wider connection to the exploitation of recources in Africa?

Thanks,

-Asim

Sources:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/africa-the-arrival-of-europeans-and-the-transatlantic-slave-trade/articles/the-ongoing-exploitation-of-africa.html

http://www.whenthenewsstops.org/2014/06/neo-colonialism-and-changing-nature-of.html

When thinking of a civic artifact that advertises a commonplace in American Culture, my mind immediately goes to certain racial stereotypes that have been perpetuated by media propaganda, art, and entertainment. For example, the early 20th-century minstrel characters such as the Mammy, Sambo, and Jim Crow were all created by southern white people in efforts to justify slavery and fight back against reconstruction.

While it is now commonplace in 2023 to reject these ideas as outdated and unacceptable, they were in fact justifiable civic artifacts at the time when they became popular. The rhetorical situation was that the entire political, social, and economic structure of America (specifically the South) was dependent on free labor and the institution of slavery. When Black people were freed and granted American citizenship, their liberty became a threat to the hundreds of thousands of Whites whose livelihood was reliant on oppression.

In response to this, people started making art, comics, decorations, films, music, and live performances that told exaggerated stories of Blacks in the South. Minstrelsy became the national art form by 1848 and continued that way through the turn of the century and into the era of Jim Crow.

The persuasiveness of these civic artifacts was due to the specific stereotypes they depicted. One particular minstrel character was called the Sambo. This was a Black man who was lazy, docile, always happy and smiley, and enjoyed the simple childish pleasures of food and music. This depiction of Black men encouraged the necessity of slavery, showing that Blacks were helpless without being given shelter and jobs by their masters. These stereotypes gained national popularity because they played off of southern whites’ desire to maintain the status quo.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13627231/litleblacksambo.jpg)

Little Black Sambo (1935)

These stereotypes subsequently became commonplace all over the country, especially since many white Americans had never seen Blacks except in these depictions. The influence of these civic artifacts continues today, and that’s why it’s important to investigate them so that we may work on reducing inequalities that stem from this systemic oppression.

Sources:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Little_Black_Sambo_poster_1935.jpg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tTLj378lWi8Links to an external site.

(This is a very detailed video on the topics I address in this post)

Welcome to Sites At Penn State. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!