Introduction (30 sec):

- My favorite store growing up? Five and Below. There, I could buy anything. I was rich. I had options. I felt powerful. The dollar bill is magical in that it changes how you perceive yourself or your surroundings. In the Nineteenth Century, the bill was invented to fund the Civil War, but its intended purpose has deviated since. Civically, the bill is meant to engage its owner in creating opportunities, but if the holder declines, he becomes controlled by the bill. The bill represents the civic imbalance between doing what’s right and doing what’s wrong, and its power is unfettered. The bill can spend, send, and condescend, but our inability to be fully satisfied must prevent it from becoming the ultimate source of wealth.

Spend (1 min):

- Main idea: Payment

- The dollar is a means for exchange

- It’s used to purchase tangible items

- More implicitly, it’s used to purchase and satisfy feelings as well as produce emotions: entertain, quench hunger or thirst, make happiness

- The irony of money: we earn it to spend it. If we could be fully satisfied, we would stop spending it. Instead, spenders are involved in a vicious, unending cycle of earning and buying

- Some things can’t be bought. A flaw of money: the feelings it buys are temporary and felt on the surface

- Transition/Commonplace: Money can be used to transact because we give it worth; it’s valuable.

Send (1 min):

- Main idea: value

- To dollar can be transferred

- It’s mobile and meant to be shared

- It can be stored and invested

- These actions are logical and based on numbers and data

- Money can create opportunities and destroy others

- Donations provide relief to those in need

- For a parent, earning money may mean less time as a family

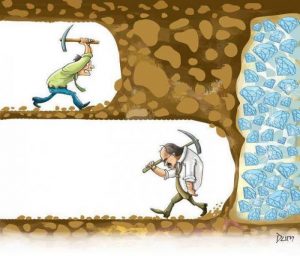

- Chasing money takes up time and chews away at “priceless” opportunities

- Transition: Money can be inherited, but inherited money defeats the idea of money = worth. Therefore, the bill can deceive.

Condescend (1 min):

- Main idea: Power

- Commonplace: Money and status are directly related

- More money = smarter, works harder, luckier

- The bill gives credibility

- Money is used as a means of persuasion and as an incentive

- Because we place value on the dollar bill, it can control us

- Some argue that money is the root cause of evil. The bill doesn’t cause evil; its value does. Consumers are to blame for this

- Transition: How everything comes together as a civic artifact: Money is a mobile, dynamic way to pay for things because it’s powerful. Why is it powerful? We put too much value on it. We need to change the way we think.

Conclusion (30 sec):

- We need to consider that the bill can’t buy everything, and for that to happen, we need to put less value on it. As a result, it’ll have less meaning in our lives. It’s our civic responsibility to act in accordance with our own moral codes. The bill adapts: With it, we’re controlled. Without it, we’re rich. Thank you.