INTRODUCTION

A month ago, Skytrax revealed its annual list of top airports. The top ten was populated with familiar names, like Tokyo Haneda, Seoul Incheon, and Munich. However, in a big departure from previous years, Singapore’s Changi Airport was knocked off its top spot by Doha Hamad airport in Qatar.

When talking about infrastructure, it’s impossible to ignore airports. According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, there were over a billion flights (domestic and international) inside the US in 2019. In an age of globalization and the breakdown of borders across all mediums, it’s critical for any country to have a robust system to make air travel safe, efficient, and enjoyable.

Let’s take a look at a few of the things that make airports great, along with examples from the Skytrax top ten list to illustrate what I mean:

CONNECTIVITY

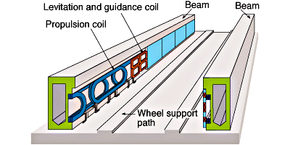

The point of any infrastructure is to increase connectivity and efficiency of travel. Therefore, it’s important for airports to provide easy access to public transportation so that travelers can reach their destination with minimal stress and delays. Below is a schematic of rail lines connecting Haneda Airport in Japan (which handles 80 million passengers a year) to Tokyo. There are two easily accessible train routes that transport passengers to the city within thirty minutes, in addition to the network of roads and highways.

INTUITIVE LAYOUT

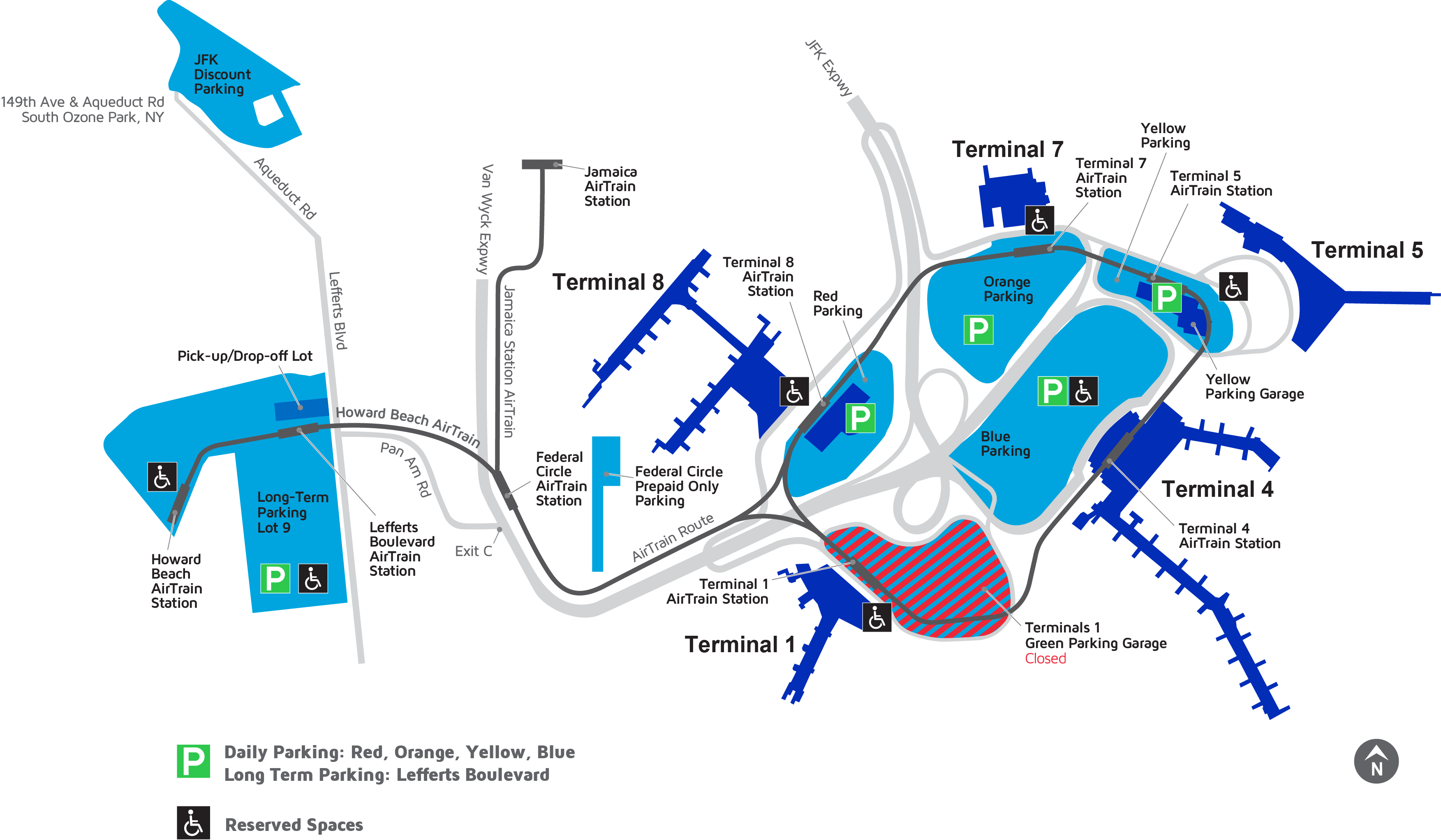

Just as important as ease of travel in and out the airport is connectivity within the airport. Anyone who has traveled through John F Kennedy International Airport can understand the importance of good integration. Made up of six independent terminals, constant delays are unavoidable at JFK, and the lack of well-integrated, easy to find shuttles makes it tedious to go from one end to another. Additionally, the lack of good, affordable dining options when the airport sits next to one of the most culturally diverse cities on earth is baffling.

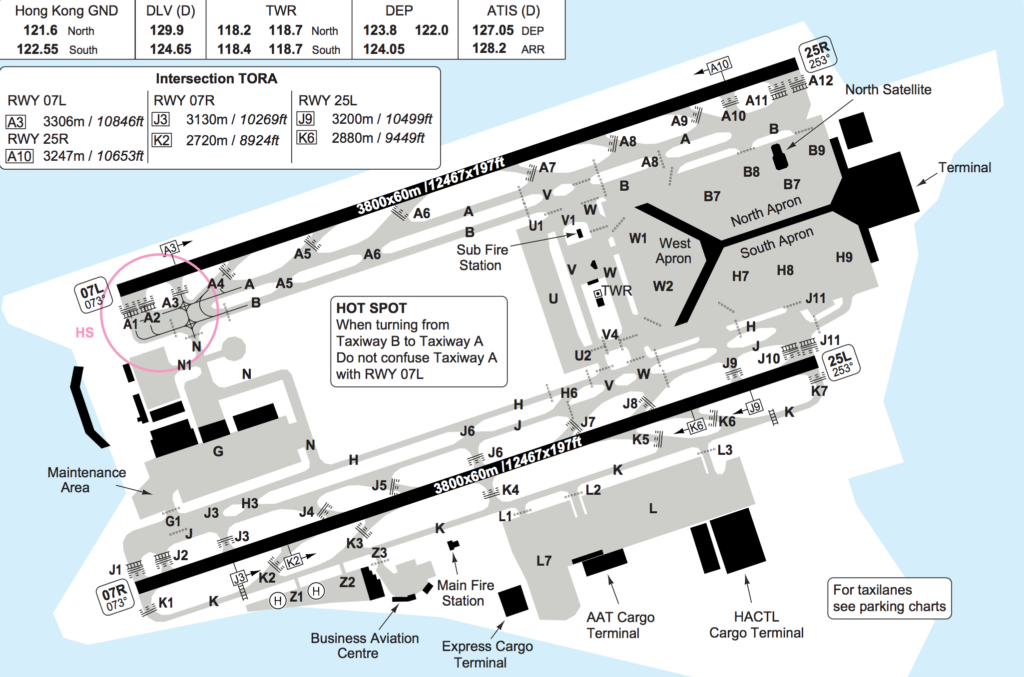

In comparison, Hong Kong International Airport (which sees more annual passengers) is significantly more compact, funneling seventy million passengers in 2019 in just two terminals. This decreases the distance travelers must walk to get to their flights. Additionally, there are a plethora of retail and dining options available for guests, improving the overall experience of the stay.

DESIGN AND CHARACTER

Finally, airports (especially international ones) are meant to serve as the gates to the cities or countries they reside in. Therefore, they should have design elements that celebrate the unique cultural aspects of their location.

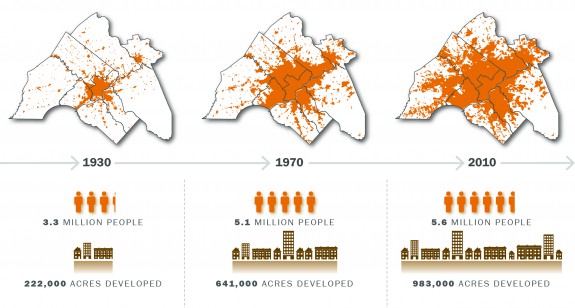

For example. Singapore prides itself on being the world’s greenest city. Despite being so densely populated, it has the highest urban concentration of trees on Earth, with a plethora of parks, roadside plants, and green buildings that contribute to the city-state’s sustainability and health goals.

Accordingly, Singapore’s Changi Airport seamlessly incorporates botanical life into its architecture and functionality. For example, the “Jewel Changi”, serves as both a hub connecting three of the airport’s four terminal and a place where guests can relax between flights. Additionally, the indoor playgrounds and massive adult-size slide in terminal 3 further contribute to the free, forest-like feel.