Welcome back to the final post of this series. Hopefully over the past couple months you’ve gained some insight into keeping houseplants alive (and maybe even thriving). For this final post in the series, we’ll be talking about propagation of common indoor plants, specifically the different types of vegetative propagation.

When most people think of growing new/more plants, their minds go to seeds. However, for many common houseplants, there is a simpler and also significantly faster way: Vegetative propagation.

Vegetative propagation is a type of asexual reproduction for plants in which a piece of plant material (such as a leaf, root, or stem) is separated from the mother plant and grown into a whole new plant of its own. Compared to seed propagation, vegetative propagation can be significantly faster (plants are already larger when they start growing) and sometimes also easier (no need for specific germination requirements like scarification/stratification etc.). Additionally, there is the added benefit that all plants propagated vegetatively are genetically identical (clones) to the original plant, which means the new plant will be exactly the same as well.*

*There are some very specific instances in which traits result from chimeras (some cells have mutation but others do not) and during propagation the mutated cells are lost which results in the clone having a slightly different phenotype than the original plant. This is the case with some variegated snake plant cuttings reverting back to a non variegated form.

Stem Cuttings

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/make-more-plants-with-cuttings-1402474-V3-b7fbab04ad36414f8c6352ad73bf1488.png)

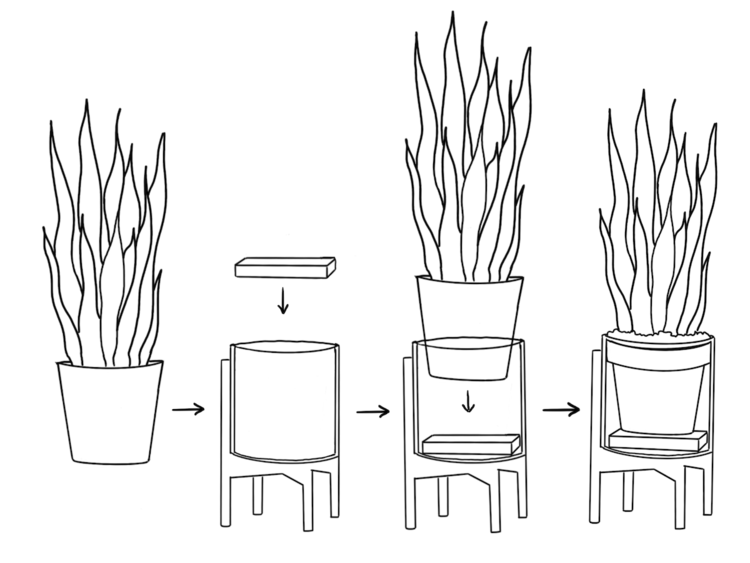

Probably the most common type of vegetative propagation is through stem cuttings. A cutting is simply a piece of plant you cut off the original for the purpose of creating a whole new plant (and a stem cutting is a piece cut specifically from the stem of the original plant). The way this works is that plants have certain cells in their roots and shoots which can change type and create roots on stem tissue or shoots on root tissue.

In order for this to work, the plant needs to stay alive long enough for the new roots/leaves to grow. However, a piece of stem or leaf without roots is very limited in its ability to take up water, so it is important that these cuttings be kept moist to prevent them from drying out.

For most vining houseplants (pothos, ivy, philodendron, monstera, etc.) the easiest way to take a cutting is to cut off a section of the stem with at least 1 or 2 nodes (where a leaf meets the stem)

It is important to include a node on the cutting (for most plants) because the cells which have the potential to develop into roots are only found on the nodes. Strip the leaves from the lowest node and simply place the cutting in either moist soil or a glass of water (ensure the node is below soil/water line). Placing in soil is a little easier for more experienced people, because you won’t have to transfer the cutting from water to soil later on, but many people like to start their cuttings in a glass of water because they can see the roots developing. If placing in soil, make sure to keep the soil moist (but not soaking wet) at all times, to prevent the cutting from drying out*. In water, just make sure to change out the water for fresh water every couple days. Keep developing cuttings in a bright area but out of direct sunlight (direct sun dries them out too fast, but some light is still needed to allow photosynthesis to create energy to grow new roots).

*Propagating cacti or succulents is a little different. Because these plants store so much water in their tissues, they don’t need to be placed in moist soil and should actually be kept dry (even letting the cut stems sit out for a couple days is encouraged to let the wounds callous over). Watering these cuttings usually just leads them to rotting.

After a couple weeks, you’ll start to see roots developing like above. If you’ve got your cuttings in water, you can now move them to soil. Be sure to keep the soil a little more moist than usual for the first week or so after transferring from water to allow the roots to adjust. If you started the cuttings directly in soil, you can simply start to wean off the watering until the cutting is being watered like a normal plant.

Some plants can also be propagated from just leaves instead of stem cuttings. This includes most succulents and things like snake plants. To read more about leaf cuttings and succulents, click here. I also mentioned root cuttings as a way to propagate plants. This technique isn’t common for houseplants, but if you’re interested here is some further reading on it. The on

Some people/websites suggest using rooting hormone to help increase the root growth on cuttings. In my experience this isn’t necessary for houseplants but its beneficial for some woody plants (like trees/woody herbs). Regardless, if you’re interested you can purchase it on Amazon.

And that concludes the Indoor Garden Guide. Hopefully you learned enough that you feel comfortable taking a shot at growing some plants yourself. Goodluck, and enjoy this warm spring weather!

![Elite Gourmet 5 Tier Food Dehydrator [EFD319] – Shop Elite Gourmet - Small Kitchen Appliances](https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0421/1235/2414/products/efd319_main_1024x1024.jpg?v=1605028222)

/home-canning-preserving-pickling-food-stored-on-wooden-storage-shelves-185065365-582871743df78c6f6a4a0f8a.jpg)