When a pharmaceutical industry announces a drug, they’ve patented it so that they are the only ones legally allowed to manufacture it or any other drugs deemed similar enough. When a drug is patented, the pharmaceutical company often keeps the price of the drug high, allowing them to make a profit off of the drug. Most people criticize pharmaceutical companies for this as they are making a profit off of the wellbeing of others, something most people agree isn’t ethical. Pharmaceutical companies, on the other hand, argue that they have to price them high while they still have the patent in order to cover all the costs of making the drug in the first place.

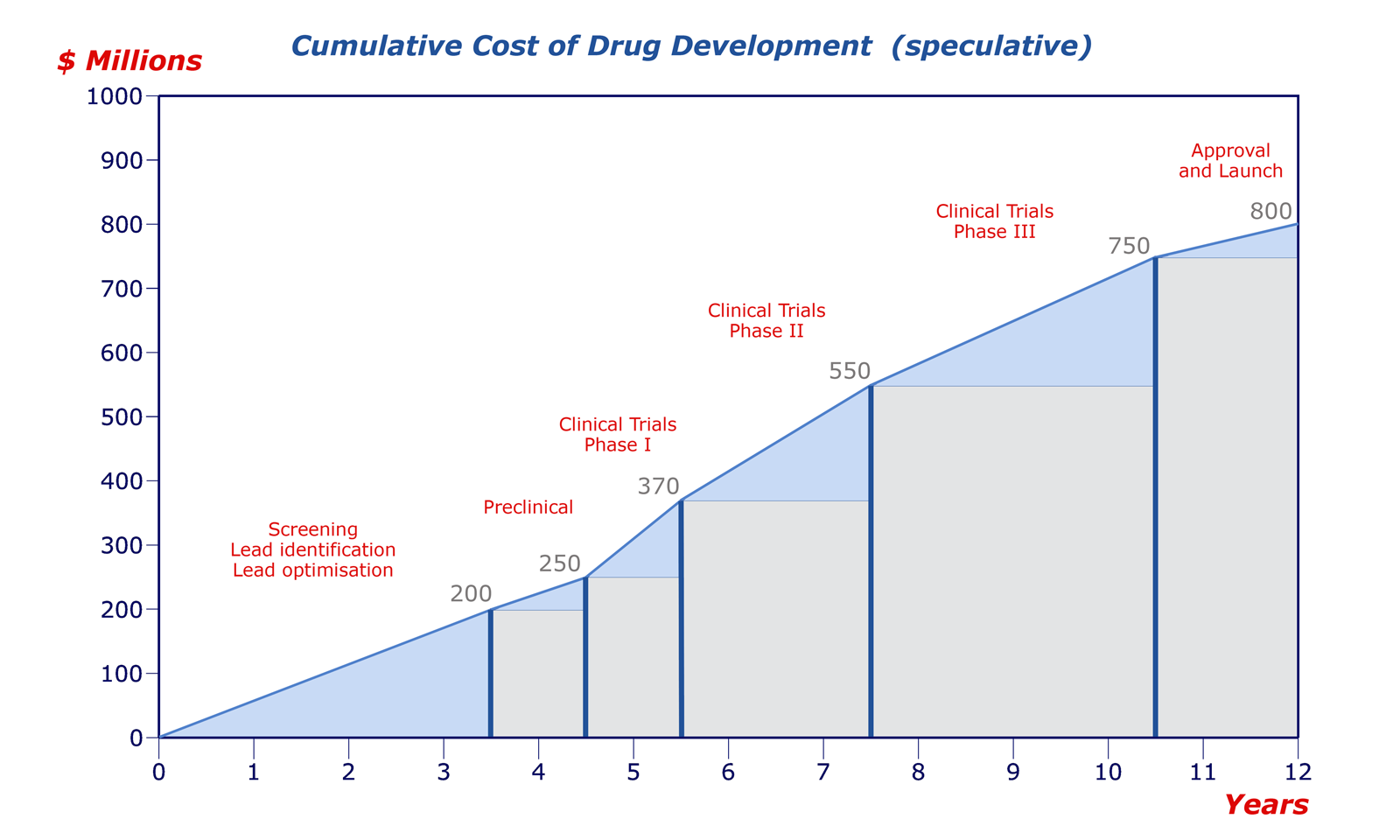

Drug patents last for 20 years since the day of their filling date. While that may seem like a long time, most drugs get patented very early in their development career. Drug discovery companies want to reserve that chemical space to prevent other companies from poaching their work and patenting it themselves. However, they also want to balance it with patenting it too early (don’t want your patent to run out before you can release the drug to market). When one considers that most drugs take 12-15 years to make it to market once their initial filing day, the effective patent life is typically around 5 years.

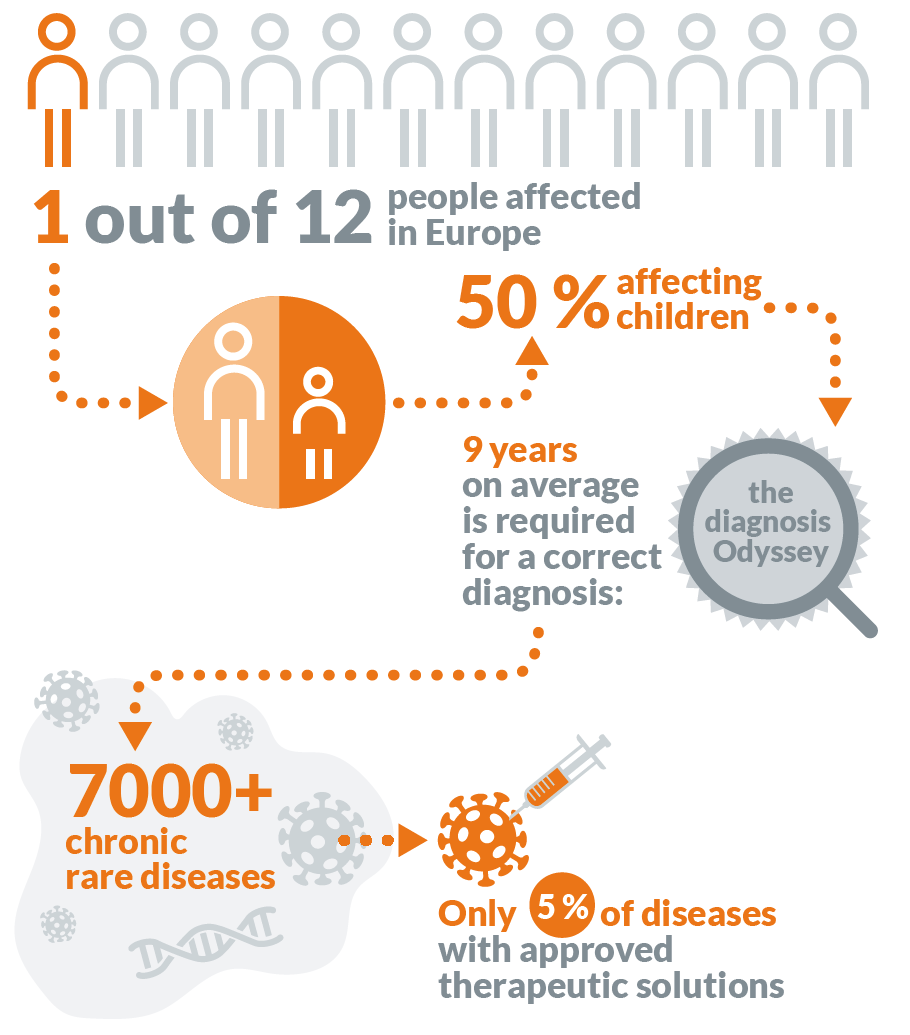

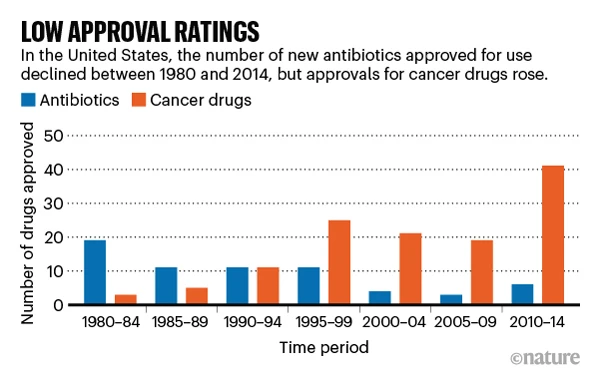

In those 5 years, pharmaceutical companies need to both recover the $3.5 billion dollars spent to develop the drug and then some in order to ensure that their investors have an incentive to invest with them again in the future. So while it is problematic that pharmaceutical companies try to make as much of a profit as they can in those 5 years, if they didn’t, no investor would give them their money — which would me no drug gets developed. Considering that cancer, genetic conditions, and illnesses aren’t going anywhere, we will continue to rely of these pharmaceuticals, and unless the government steps in to sponsor and provide incentives, this system isn’t going to change any time soon.

Another perspective in this debate is those who feel that the 20 year patent life is too little, especially when art copyrights have lasted for much longer than that. They often argue that those advancement are much more impactful than those entertainment based ones, so why should there be a smaller monetary incentive for people to pursue development of these pharmaceuticals. However, many feel that there should be a tighter limit on pharmaceuticals because of their importance for the broader community, people should be able to purchase and use them without incurring significant damage to their financial wellbeing.

Obviously this is a complex issue that won’t be shaped over night but rather will be gradually shaped over decades by the changing sentiments of investors, the government and its role in pharmaceutical discovery, and the general populace.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/what-is-a-double-blind-study-2795103_color1-5bf4763f4cedfd002629e836.png)