Earlier this week, my Facebook feed was peppered with the announcement of Jessica Chastain’s launching of an all-female production company. This news stemmed from the recent Oscar and Grammy award seasons, which brought with them a slew of criticisms of the largely white male pool of nominees coming from an industry dominated by white males. (Take a good look at the graph in the Forbes article hyperlinked above; these shocking statistics are from 2015.) Feminists often cite the portrayal of women in films and media as a source of ongoing sexism and violence against women. If you’re wondering what that means, you don’t have to look any further than Rear Window.

I walked out of Carnegie this past Monday a little dazed and deeply unsettled by Hitchcock’s movie. The acclaimed director’s portrayal of women violated every feminist stance possible. The women in Rear Window are obsessed with marriage and how they are viewed by men. They enjoy being victims of violence and abuse. They exist only to please the perverted men they love.

Hitchcock directed the movie to exclusively show the male gaze. There are only three perspectives, and all three are male: Jeff, Hitchcock’s subjective camera, and Thorwald briefly at the final climax. As the audience, we see what these men see, and despite our own race, gender, sexuality, etc., we view the movie and the action as white men. (And as most directors, Hitchcock tries to get us to empathize with his (white, male, hetero) protagonists.) This choice of direction automatically objectifies women; we must divine their thoughts and intentions through the lens of the male gaze, which frequently stops at their physical appearance. Miss Torso’s plotline until the very last scene can be summed up as “eye candy,” and even when we see her partner come through the door, her greatest ambitions are shown to be domestic bliss. Lisa’s first scene and last scene, despite her “character development,” are identical: Massive shots and slow pans of Grace Kelly not speaking and looking gorgeous, or in other words, even more eye candy. Women are to be seen and sexualized, but not heard.

Hitchcock directed the movie to exclusively show the male gaze. There are only three perspectives, and all three are male: Jeff, Hitchcock’s subjective camera, and Thorwald briefly at the final climax. As the audience, we see what these men see, and despite our own race, gender, sexuality, etc., we view the movie and the action as white men. (And as most directors, Hitchcock tries to get us to empathize with his (white, male, hetero) protagonists.) This choice of direction automatically objectifies women; we must divine their thoughts and intentions through the lens of the male gaze, which frequently stops at their physical appearance. Miss Torso’s plotline until the very last scene can be summed up as “eye candy,” and even when we see her partner come through the door, her greatest ambitions are shown to be domestic bliss. Lisa’s first scene and last scene, despite her “character development,” are identical: Massive shots and slow pans of Grace Kelly not speaking and looking gorgeous, or in other words, even more eye candy. Women are to be seen and sexualized, but not heard.

So what happens when the male gaze lingers past the curves and starts to look into the lives of these women? The answer is three victims of abuse.

The first is Lisa, who suffers emotional abuse in trying to domesticate Jeff. In her first scene, Lisa is, by 1950’s standards, the perfect woman. Gorgeous, fashionable, and ready to take care of her man. But her man still doesn’t want her, and that limits Lisa’s character development to pleasing Jeff. In the final scene, Hitchcock further infantilizes her by showing she has not really developed at all; she puts down her book and picks up a fashion magazine with a smile.

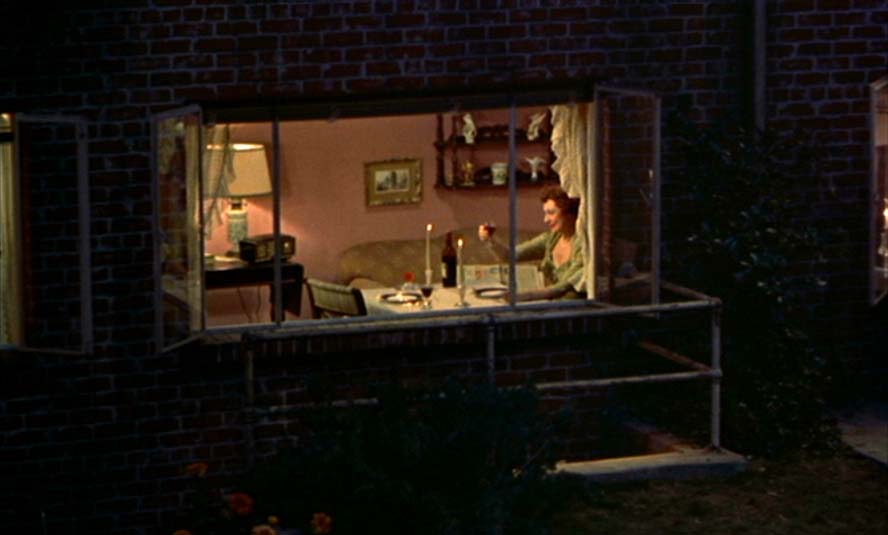

The second is Miss Lonelyheart, also seeking domestic bliss. She practices her date etiquette, prims and trims her appearance, and then puts her plan into action by hanging out at a cafe. Her efforts are met with an attempted rape, which Lisa and Jeff watch uncomfortably, neither of them reaching for a phone to call the police. Jeff has just finished asking Doyle to look into a murder he didn’t actually see happen, yet when he witnesses a crime about to happen before his very eyes, his instinct is to watch and say nothing. This incident foreshadows a rape and murder that happened ten years after the release of Rear Window, the famous Kitty Genovese case that launched research by psychologists into the Bystander Effect. Between 37 and 38 witnesses, all neighbors in her Queens apartment block, saw or heard Kitty being stabbed and raped, but not one of them intervened or called the police.

The third woman is Mrs. Thorwald. She is sick and nags her husband, and as a result, is murdered by him. One thing that struck me is that Hitchcock, in his attempt to make his murderer seem like a normal fellow, only gives those two reasons for Thorwald’s decision to kill his wife (that she is sick and nags him). Again, this furthers the argument that women are meant to be seen and sexualized (and should therefore beautiful, not sickly) and not heard. Hitchcock further supports this by showing Lisa sneaking Mrs. Thorwald’s wedding ring on her own finger, symbolically marrying a wife-murderer. Lisa is the perfect female character to be shown doing this, having already taken Jeff’s verbal abuse to heart and acting upon it.

The third woman is Mrs. Thorwald. She is sick and nags her husband, and as a result, is murdered by him. One thing that struck me is that Hitchcock, in his attempt to make his murderer seem like a normal fellow, only gives those two reasons for Thorwald’s decision to kill his wife (that she is sick and nags him). Again, this furthers the argument that women are meant to be seen and sexualized (and should therefore beautiful, not sickly) and not heard. Hitchcock further supports this by showing Lisa sneaking Mrs. Thorwald’s wedding ring on her own finger, symbolically marrying a wife-murderer. Lisa is the perfect female character to be shown doing this, having already taken Jeff’s verbal abuse to heart and acting upon it.

The movie ends with domestic justice: Thorwald is sent to jail, Miss Lonelyheart finds a companion in the struggling musician, and Lisa metaphorically lets her hair down for Jeff by wearing jeans and attempting to read an adventure book. Both of the surviving women have reached their peak happiness in the prospect of marriage, and both are seen in their male partner’s apartment, conforming to the man’s life instead of their own. With the final scene, Hitchcock imprisons the women in their endless quest to please men, with no indication of further ambitions or further capacities.

I realize now that my word count is obscene, but for any of you interested in the feminist and psychoanalytical implications of Rear Window and other Hitchcock films, here is a great essay by Laura Mulvey from 1973 that was published as an article in Screen in 1975.