Was I the only person who felt that Henry Fonda was a bit out of place in this movie? The only other movie I’ve seen with him is 12 Angry Men, and I certainly liked him there, but in this movie he somehow stuck out like a sore thumb. Every other character seemed to meld perfectly into the environment, but I could only see Fonda as a Hollywood actor. I think part of it could have been his makeup. We saw in class how he was made not to look too dirty so that his Hollywood charm could shine through. I think this factor, in part, made him stick out from his surroundings. But I also just felt that his delivery was not on point. He did not sound conversational, but instead like he was rehearsing speeches, and his voice did not sound like that of a farmer’s at all. You could tell he was a city slicker from the way he spoke.

I found some pretty interesting tidbits about the acting. Apparently Darryl Zanuck prefered Tyrone Power for the role of Tom Joad, but John Ford convinced him Henry Fonda was right for the part. As a compromise, Zanuck had Fonda sign a seven-year contract with Fox even though Fonda tried to stay an independent actor. In the future, he came to resent this contract.

John Ford’s process for directing actors is very interesting as well. Apparently John Ford preferred to do everything in one take because he thought rehearsing scenes would make them too artificial and that scenes have the most emotion in the first take. I was surprised to read about this process because I’ve read lots of stories before with talented directors (especially Kubrick) being very specific and requiring tons of takes. Henry Fonda talks about Ford’s directing in his autobiography Fonda, My Life:

We both had enough sense not to tell Ford how we felt, though, because we’d worked for him before and you didn’t make suggestions to Pappy Ford. He’d say ‘You want to direct this film, Huh?’ And you were on the shit list right away. He didn’t like to have anybody ever recommend anything…

Well, the scene I’m talking about started in the tent where Tom Joad goes in and wakes up Ma. He’s going away, and he wakes her up. Without waking the other people in the tent, Pa and the kids.

I had to light a match, and the cameraman, Gregg Toland, Rigged a light in the palm of my hand with wires going up my arm. The light, which was supposed to be a glow from the match, had to light Ma’s face just right. It took half an hour to set up that piece of business.

Then I tapped her and she opened her eyes and she went outside with me. We walked around the tent and up to the bench that was the foot of the dance floor. Ford wouldn’t let me get into the dialogue. By the time he was ready Jane Darwell and I were like racehorses that wanted to go. ‘Hey, boy have we got a scene. We want to show you.’

Then with Ford’s intuitive instinct, he knew when we were built up. We’ve never done it out loud, but Ford called for action, the cameras rolled, and he had it in a single take. After we finished the scene, Pappy didn’t say a word. He just stood up and walked away. He got what he wanted. We all did. On the screen it was brilliant.

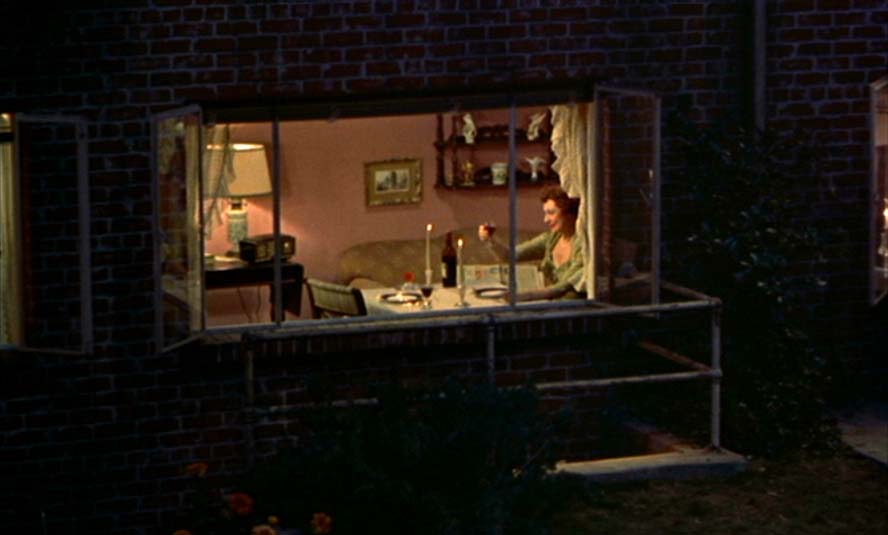

I also wanted to briefly discuss the cinematography because this was the first film we’ve seen in this course where I felt the cinematography was impressive. We got many nice, wide artistic shots like this:

Shots like this were rare in anything we’ve seen before, but they populated the mise-en-scene of Grapes of Wrath. Also, the point-of-view shot of the car driving into the Hooverville was just pure eye candy for me. When there’s so much detail put into a set like that, anything on film can be beautiful, even things that are dirty. (If you want to see how things that are excessively filthy can be beautiful on camera, check out Hard to Be a God (2013). The entire film is like that Hooverville scene to the max.)

Interestingly enough, the cinematographer of this film, Gregg Toland, went on to be the director of photography for Citizen Kane the next year, and if any of you have seen that, you know it is a great achievement in cinematography.