Practitioner Interview PODCAST: How Web 2.0 Tools & Social Media Influence Teaching & Learning

Gloomy Sunday afternoons seem the perfect opportunity for: a) catching up on much-needed rest, b) simmering delicious crock pot meals, c) discussing tech tools with teachers, or d) all of the above. If you happen to be as fortunate as I, the answer is d) all of the above … and the questions are awaiting your listening ear. While cozy in my most comfy sweats slow-cooking a great chicken alfredo and following doctors’ orders to take it easy, I just happened to create my very first podcast while enjoying a great conversation with my friend and former colleague Ms. Lauren Smith.

Lauren teaches secondary English for Commonwealth Cyber Academy, an online Pennsylvania public charter school. About five years ago, I served as Lauren’s faculty mentor as she arrived at LCCC as a brand-new English instructor. A great friendship blossomed between us, as did a beautiful start to a rewarding career for Lauren as an educator. And while she outgrew her environment at the small college satellite center where we first met, Lauren will never outgrow her love of teaching and learning. (That has always been our most fundamental bond.) She transitioned into some long-term substitute teaching about three years ago, and from there was presented a unique opportunity to teach in a way she’d never expected: online. Initially, the cyber environment proved uncomfortable for Lauren – but the more she got her feet wet, the more she was willing to get her hands dirty … and to learn as much as possible about her new teaching space. Now, two years later, Lauren thrives in a learning ecosystem where she never expected to find herself – and both she and her students are better for it.

Lauren utilizes an abundance of online and embedded resources that I would consider exploring in my own practice. She ranks Google applications high on her list of facilitation tools, and her comfort with the breadth of that particular suite encourages me to learn more about how I too might incorporate these aspects into my instructional “toolbox.” She also mentioned Zoom and Skype, both of which I have used as a student but not as a teacher; I would welcome incorporating more self-generated audio and video into my teaching, as I am often providing remote instruction due to the hybrid nature of my courses. Overall, I think the big take-away from this interview is not to shy away from experimentation with different platforms, and not to forget to utilize our human resources as well as our technological tools.

My favorite aspect of this interview is the love of teaching and learning that Lauren and I share. I also must acknowledge the empowering support we provide to each other, as evidenced in our mutual positive regard both in this podcast and in real life. I feel this is an important aspect to note because professional women can often become highly competitive in the workplace, and by doing so can stifle and alienate their colleagues. (Both Lauren and I have experienced that kind of negativity in the past.) When we adopt a collaborative mindset in which we nurture and respect our unique gifts and talents while also learning to embrace a shared mission – we can accomplish truly great things.

My favorite aspect of this interview is the love of teaching and learning that Lauren and I share. I also must acknowledge the empowering support we provide to each other, as evidenced in our mutual positive regard both in this podcast and in real life. I feel this is an important aspect to note because professional women can often become highly competitive in the workplace, and by doing so can stifle and alienate their colleagues. (Both Lauren and I have experienced that kind of negativity in the past.) When we adopt a collaborative mindset in which we nurture and respect our unique gifts and talents while also learning to embrace a shared mission – we can accomplish truly great things.

Reflection: Podcasting presents challenges I did not expect! I produced 28 minutes of content and had to edit judiciously in order to yield a final product somewhere close to the target length of 10 minutes. Sound editing is a meticulous process and proved somewhat time consuming for me (I acknowledge this could be attributable in part to my own recent health setbacks). Another challenge I experienced was my great feeling of urgency to keep the interview moving while simultaneously enunciating with precision, trying to relax, and proceeding primarily unscripted. With the exception of providing Lauren a short list of questions to anticipate, I performed absolutely no advance preparation for the interview – there was no coaching my interviewee nor compelling her to respond in any certain manner. We spoke briefly and generally about my LDT courses and why I’d decided to pursue another advanced degree, and then I simply began recording with Audacity. While I appreciate the authenticity of the approach I took, in retrospect I would slow down and deal with dead air space in order to create content a bit more easily editable. However, all things considered – as a first experience with podcasting this assignment proved itself awesome, and I am looking forward to doing it again!

Reflection: Podcasting presents challenges I did not expect! I produced 28 minutes of content and had to edit judiciously in order to yield a final product somewhere close to the target length of 10 minutes. Sound editing is a meticulous process and proved somewhat time consuming for me (I acknowledge this could be attributable in part to my own recent health setbacks). Another challenge I experienced was my great feeling of urgency to keep the interview moving while simultaneously enunciating with precision, trying to relax, and proceeding primarily unscripted. With the exception of providing Lauren a short list of questions to anticipate, I performed absolutely no advance preparation for the interview – there was no coaching my interviewee nor compelling her to respond in any certain manner. We spoke briefly and generally about my LDT courses and why I’d decided to pursue another advanced degree, and then I simply began recording with Audacity. While I appreciate the authenticity of the approach I took, in retrospect I would slow down and deal with dead air space in order to create content a bit more easily editable. However, all things considered – as a first experience with podcasting this assignment proved itself awesome, and I am looking forward to doing it again!

Check out these articles for more information on educational podcasting:

Past, Present, and Future of Podcasting in Higher Education

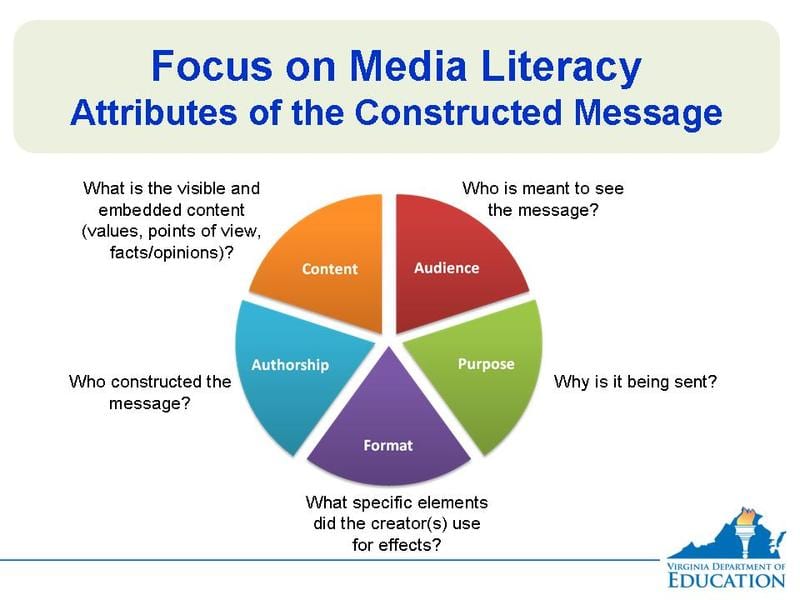

Our collective theme for blogging this week resounded in the challenges media literacy instruction presents to both teachers and learners, and in constructing interventions to address those difficulties. Interestingly, while we all opted to work with the Buckingham article, it resonated with each of us a little differently. In general, however, the issue of source credibility and its relationship to prerequisite critical thinking skills ranked high on our collective problem-solving agenda.

Our collective theme for blogging this week resounded in the challenges media literacy instruction presents to both teachers and learners, and in constructing interventions to address those difficulties. Interestingly, while we all opted to work with the Buckingham article, it resonated with each of us a little differently. In general, however, the issue of source credibility and its relationship to prerequisite critical thinking skills ranked high on our collective problem-solving agenda. “Similar to this graphic organization of web resources,” Justice proposes, “the periodic table is associated with ordering known elements into a system. In the future, I hope media literacy can be taught in such a way that people will immediately associate media elements with the instantly recognizable periodic chart. Imagine your digital literacy as it conforms with these organized columns. Are there elements missing, resources that you think are essential which deserve being petitioned to join?”

“Similar to this graphic organization of web resources,” Justice proposes, “the periodic table is associated with ordering known elements into a system. In the future, I hope media literacy can be taught in such a way that people will immediately associate media elements with the instantly recognizable periodic chart. Imagine your digital literacy as it conforms with these organized columns. Are there elements missing, resources that you think are essential which deserve being petitioned to join?”

Empowering learners by encouraging critical thinking comprises an important interventional role. “An important piece to address when teaching digital media literacy,”

Empowering learners by encouraging critical thinking comprises an important interventional role. “An important piece to address when teaching digital media literacy,”

Buckingham (2007) identifies a new digital divide wherein “a new and widening gap between young people’s out-of-school experiences of technology and their experience in the classroom” (p. 112) contributes to a disconnect between knowing how to find information and knowing how to discern credibility of said information. This has become a problematic theme in my courses. For example: When I ask my students to utilize “peer-reviewed sources,” what I mean is that I want them to find, read, and evaluate scholarly journal articles … what I do not mean is that a source should be considered reliable if at least two of their Facebook friends re-tweeted the same post. (I’ve come to accept that we are not always speaking the same language.)

Buckingham (2007) identifies a new digital divide wherein “a new and widening gap between young people’s out-of-school experiences of technology and their experience in the classroom” (p. 112) contributes to a disconnect between knowing how to find information and knowing how to discern credibility of said information. This has become a problematic theme in my courses. For example: When I ask my students to utilize “peer-reviewed sources,” what I mean is that I want them to find, read, and evaluate scholarly journal articles … what I do not mean is that a source should be considered reliable if at least two of their Facebook friends re-tweeted the same post. (I’ve come to accept that we are not always speaking the same language.)  According to Buckingham, strategies for seeking deeper media literacy include “applying and extending existing conceptual approaches, … addressing the creative possibilities of digital technologies, … and exploring the potential of emerging forms of participatory media culture” (p. 112). This validates my current emphasis on the incorporation of more interactive media literacy initiatives available to students through my course LMS. In rethinking my own practices and providing more growth opportunities within our existing learning ecology, both I and my students gain new insight.

According to Buckingham, strategies for seeking deeper media literacy include “applying and extending existing conceptual approaches, … addressing the creative possibilities of digital technologies, … and exploring the potential of emerging forms of participatory media culture” (p. 112). This validates my current emphasis on the incorporation of more interactive media literacy initiatives available to students through my course LMS. In rethinking my own practices and providing more growth opportunities within our existing learning ecology, both I and my students gain new insight. “Many assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally savvy about what they find there….Our work shows the opposite.”

“Many assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally savvy about what they find there….Our work shows the opposite.”