How the Historical Foundations and Current Biases on Distance Education Influence Institutional Perceptions and Outcomes

Throughout its rich history, distance education (DE) has fallen under the scrutiny of an academic bias that posits remote learning experiences as “less than” the in vivo endeavors engaged at brick-and-mortar institutions. While distance learning offers equity of opportunity to historically underserved, unrecognized, and otherwise marginalized learners in the postsecondary market, it frequently falls prostrate among traditionalist views of the discipline as a diminished sector of learning science. The industrial age heavily promoted the mechanization of education to include stringent criteria on not only what qualified as learning but also where and when learning occurred; transitioning into the digital age of the 21st century warrants leadership’s reconsideration of DE as an authentic field not only through which a diverse body of learners enjoys greater accessibility to flexible, meaningful, high-quality learning experiences but also upon which to deploy multimodal initiatives that significantly increase the outreach and access of these experiences. In considering the current picture of distance education across what has become a progressively expansive landscape, we must evaluate the priorities we set, the integrity we convey, and the wisdom we exercise in serving the evolving needs of audiences across broad contexts.

While over 95% of public postsecondary institutions offer some form of distance education – primarily online courses – these offerings are not as available at smaller, private institutions both in the for-profit and non-profit sector; for exclusively online program offerings, access drops significantly as institutional selectivity rises, indicating a strong bias toward face-to-face learning experiences as “better” (Xu and Xu, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the neglected and underestimated science of DE rose in global visibility as institutions were forced to shut down; moving forward, “[a]s the world emerges out of the pandemic in fits and starts, it seems inevitable that online instruction will be a crucial part of higher education pedagogy and is here to stay for the foreseeable future” (Shankar et al., 2021). Even as digital DE becomes more visible as a viable learning modality beyond the pandemic demand for its emergency administration, problematic issues of quality versus cost prevail.

Xu and Xu (2020) issue the caveat that online learning as a perceived institutional cost-reducer often proves counterintuitive when considering quality, implementation, and infrastructure. Through qualitative analysis, Ortagus and Derreth (2020) evaluated interview data reflective of how higher education administrators reconcile the financial and quality aspects of online learning programs; concluding the pursuit of quality as an “actionable goal” in online education, the team cautions that cost-saving measures in the development stages can potentially endanger the user-end experience and negatively influence student learning outcomes. In referencing the work of Ortagus, Lederman (2019) asserts that “even if institutions (as most do) start online programs with the goal of improving their financial situation …, they will ultimately fail unless they put the quality of those programs at the center of their strategy.”

While invested stakeholders may embrace a business model in deploying DE courses, an important – and neglected – aspect of that approach is that postsecondary education, including higher education, exists as a consumer-based (rather than compulsory) industry. In the current global economy, we can no longer rely upon brand loyalty or allegiance to an alma mater when myriad options for distance learning exist. It makes sense, therefore, to assure quality and integrity of product – i.e. the learning experience – during the assessment and design phases of development. Xu and Xu (2020) identify four areas to hone quality in the online learning environment: 1) presentation and organization, 2) objectives and alignment, 3) interpersonal interaction, and 4) technological integration; attention to these markers not only relays quality to the consumer and promotes learning experiences founded in best practice, it also assures the most reliable return on investment for increased retention and revenue generation. Deployment of DE for dollars alone omits the most vital aspect of the learning experience – the student. In any consumer market, success is determined by a product’s capacity to reach and sustain satisfaction among its consumer base. In the case of distance learning, we need to evaluate the quality of our product and invest in the development process in order to reach strategic goals with veracity.

Innovation-resistant institutional cultures combined with flawed perceptions of distance education as not only a less prioritized learning modality but also as a workhorse primarily purposed to generate revenue for more highly prioritized traditional in-person curricula runs the significant risk of causing a ripple effect that greatly jeopardizes the quality of online learning experiences and ultimately affects the user experience. The 2022 teaching and learning edition of the EDUCAUSE Horizon Report cites online and hybrid learning among the primary areas of growth within the higher ed landscape; in fact, the report asserts that those institutions unwilling to embrace a robust digital learning landscape will be “left behind” as the consumer-base has adapted its expectations in light of the rapid shift to online contexts amid and beyond the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic. Essentially, there is no return to what once was; we must keep moving forward and DE will serve as a vital component of that trajectory while “… those resisting the adoption of remote and hybrid learning are experiencing record-low enrollments” (Pelletier et al., 2022, p. 36). We must heed the lessons of the pandemic, as well as the wisdom gleaned from distance education’s rich historic foundations, and adjust our institutional mindset toward growth – even if that outlook presents a new set of challenges. In order to expand our learning spaces, we must broaden our horizons in how we approach online and distance learning in the 21st century and invest in initiatives steeped in integrity and geared toward change.

———-

REFERENCES

Lederman, D. (2019, Sept 4). The messy conversation around online cost and quality: Asked to explain how they balance financial and academic considerations, administrators and professors say quality is key but struggle to define it. Inside Higher Ed.

Marcus, J. (2022, Oct 6). With online learning, ‘Let’s take a breath and see what worked and didn’t work’: The massive expansion of online higher education created a worldwide laboratory to finally assess its value and its future. The New York Times.

Ortagus J.C., & Derreth, R.T. (2020). “Like having a tiger by the tail”: A qualitative analysis of the provision of online education in higher education. Teachers College Record, 122(2) A80.

Pelletier, K., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Robert, J., & Arbino, N. with Al-Freih, M., Dickson-Deane, C., Guevara, C., Koster, L., Sánchez-Mendiola, M., Skallerup Bessette, L., & Stine, J. (2022). 2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Teaching and Learning Edition (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2022).

Shankar, K., Arora, P., & Binz-Scharf, M. C. (2021). Evidence on online higher education: The promise of COVID-19 pandemic data. Management and Labour Studies, 0(0).

Xu, D., & Xu, Y. (2020). The ambivalence about distance learning in higher education: Challenges, opportunities, and policy implications. In L. W. Perna (ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 35.

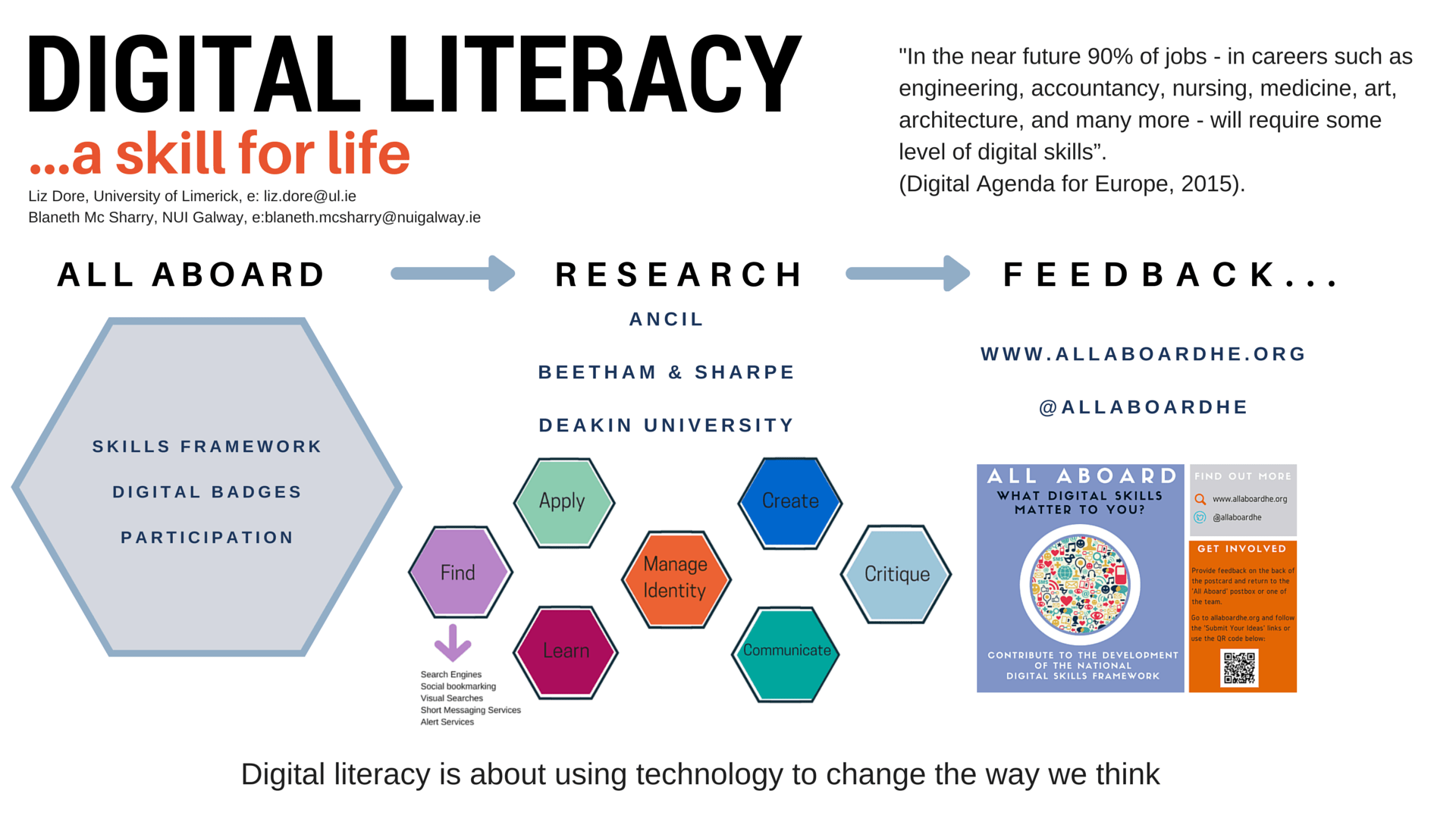

Digital learning provides users tremendous opportunities for personalization, and mobile technology readily facilitates that affordance. While past generations of learners may have been limited in the manner in which content was delivered and the degree to which that content meshed with individual objectives, the digital age offers virtually limitless possibilities for a customized learning experience that scaffolds the goals of the participants. Digital badges and e-books represent two venues through which learners can engage with meaningful content and create unique learning scenarios specific to their academic, personal, and professional needs.

Digital learning provides users tremendous opportunities for personalization, and mobile technology readily facilitates that affordance. While past generations of learners may have been limited in the manner in which content was delivered and the degree to which that content meshed with individual objectives, the digital age offers virtually limitless possibilities for a customized learning experience that scaffolds the goals of the participants. Digital badges and e-books represent two venues through which learners can engage with meaningful content and create unique learning scenarios specific to their academic, personal, and professional needs.

Additional Resources:

Additional Resources:

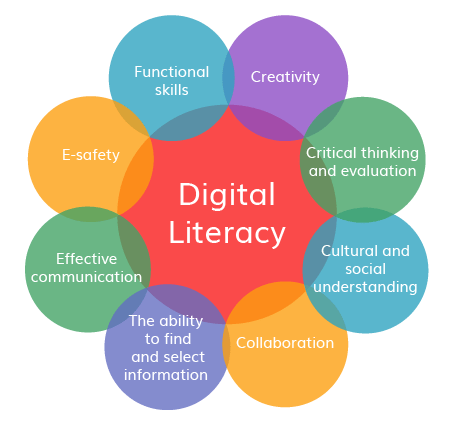

Access to technology does not predicate user aptitude. “The definition of access,” Dolan asserts “now includes the accessibility of the locations of the technology, the availability of complementary technologies (such as software), the explosion of mobile technology, and the personal skills students possess to understand and use the technology. In addition, students’ access to technology at home and the ways they use technology outside of school appear to be disconnected to their access to, and use of, technology in school” (p.19). Very much akin to the diverse accessibility challenges seen in the K-12 student population, this sense of disconnection rings true in the community college sector of higher education as well, wherein many learners arrive on campus (or, as is the case in my environment, at a satellite center within a very low SES community) with technology and mobile access but staggeringly disparate skillsets. The divide, therefore, can be observed quite literally from one desk to the next within the same classroom irrespective of any administrative assumptions of homogeneity of digital literacy.

Access to technology does not predicate user aptitude. “The definition of access,” Dolan asserts “now includes the accessibility of the locations of the technology, the availability of complementary technologies (such as software), the explosion of mobile technology, and the personal skills students possess to understand and use the technology. In addition, students’ access to technology at home and the ways they use technology outside of school appear to be disconnected to their access to, and use of, technology in school” (p.19). Very much akin to the diverse accessibility challenges seen in the K-12 student population, this sense of disconnection rings true in the community college sector of higher education as well, wherein many learners arrive on campus (or, as is the case in my environment, at a satellite center within a very low SES community) with technology and mobile access but staggeringly disparate skillsets. The divide, therefore, can be observed quite literally from one desk to the next within the same classroom irrespective of any administrative assumptions of homogeneity of digital literacy. In a similar vein, Sharples identified a study wherein alumni graduate students’ usage of mobile technology for both personal and professional purposes existed as primarily “provisional” despite their assumed literacies: “Learning is increasingly intertwined with other everyday activities such as using a search engine to look up information or taking photos and sharing them instantly with others;” in examining these patterns of mobile usage, educators should be advised to implement a blend of perspectives which may entail “uncovering existing patterns of use and working within them, but also seeking to enlarge the scope of use of mobile devices” (p. 9). While this seems sound advice, solutions surrounding collective literacy remain aloof. “Cell phones and video games are consistently purchased over desktops among low SES individuals. These devices offer entertainment, connectedness, and status at relatively affordable prices. However, lack of computers, Internet, and productivity software makes schoolwork and job searching difficult to do from home. … An important factor … is that class is dynamic” (Yardi and Bruckman, p. 3048). Essentially, many learners are equipped with devices but unprepared to use them to scaffold higher learning endeavors.

In a similar vein, Sharples identified a study wherein alumni graduate students’ usage of mobile technology for both personal and professional purposes existed as primarily “provisional” despite their assumed literacies: “Learning is increasingly intertwined with other everyday activities such as using a search engine to look up information or taking photos and sharing them instantly with others;” in examining these patterns of mobile usage, educators should be advised to implement a blend of perspectives which may entail “uncovering existing patterns of use and working within them, but also seeking to enlarge the scope of use of mobile devices” (p. 9). While this seems sound advice, solutions surrounding collective literacy remain aloof. “Cell phones and video games are consistently purchased over desktops among low SES individuals. These devices offer entertainment, connectedness, and status at relatively affordable prices. However, lack of computers, Internet, and productivity software makes schoolwork and job searching difficult to do from home. … An important factor … is that class is dynamic” (Yardi and Bruckman, p. 3048). Essentially, many learners are equipped with devices but unprepared to use them to scaffold higher learning endeavors. Digital, information, and media literacies encompass essential 21st century skills required of all learners. Environmental challenges to the attainment of these literacies do not cease upon post-secondary matriculation. The most effective way to close the digital divide, in my opinion, is to begin closing the gap with literacy training initiatives at the college level that span pre-orientation through commencement.

Digital, information, and media literacies encompass essential 21st century skills required of all learners. Environmental challenges to the attainment of these literacies do not cease upon post-secondary matriculation. The most effective way to close the digital divide, in my opinion, is to begin closing the gap with literacy training initiatives at the college level that span pre-orientation through commencement.

Appropriation, “the ability to meaningfully sample and remix media content” (Jenkins 2006) echoes the 21st century skills of critical thinking and technology literacy. The key word in this definition – “meaningfully” – resonates the impact of ongoing media immersion for college learners and compels those of us who facilitate learning to emphasize the importance of ongoing thoughtful evaluation of content.

Appropriation, “the ability to meaningfully sample and remix media content” (Jenkins 2006) echoes the 21st century skills of critical thinking and technology literacy. The key word in this definition – “meaningfully” – resonates the impact of ongoing media immersion for college learners and compels those of us who facilitate learning to emphasize the importance of ongoing thoughtful evaluation of content. Negotiation, which Jenkins (2006) describes as “the ability to travel across diverse communities, discerning and respecting multiple perspectives, and grasping and following alternative norms,” parallels 21st century skills like communication, social skills, and collaboration. This, in my opinion, is the true essence of participatory culture – to adapt within different learning environments in order to glean as much pertinent and creative authority as possible while adhering to the norms of the given community.

Negotiation, which Jenkins (2006) describes as “the ability to travel across diverse communities, discerning and respecting multiple perspectives, and grasping and following alternative norms,” parallels 21st century skills like communication, social skills, and collaboration. This, in my opinion, is the true essence of participatory culture – to adapt within different learning environments in order to glean as much pertinent and creative authority as possible while adhering to the norms of the given community.

3) My children, as digital natives, are far better participants in electronic play than I am as a digital immigrant. In short, they mock me.

3) My children, as digital natives, are far better participants in electronic play than I am as a digital immigrant. In short, they mock me.

When further questioned as to why this particular task would prove so difficult in my context, my rationale went a little something like this: “I teach at a community college extension where the majority of my students are so far removed from an authentic community of inquiry, it is an enormous challenge just to get them on board with doing research at all! Most of them do not possess the information literacy skills necessary to distinguish popular sources from scholarly sources, and I spend a great deal of time during the course of any given semester trying to teach them how to determine the credibility of information. These are the same people who make mistakes within the LMS discussion threads and rather than go back and edit or amend their work they send personal messages to me imploring me to erase their comments because they are embarrassed over what is essentially their own learning process! If I unleashed them into the global community of online information with full editing rights and an assignment to contribute to a live wiki, they’d have to exhibit a considerable increase of investment. They’d have to produce real content. They’d have to do GENUINE research because they’d certainly be corrected quickly enough by other contributors. They wouldn’t have a safety net, you know. They’d be held to a much higher standard of accountability, and it’d be … .” My voice trailed off. (Insert

When further questioned as to why this particular task would prove so difficult in my context, my rationale went a little something like this: “I teach at a community college extension where the majority of my students are so far removed from an authentic community of inquiry, it is an enormous challenge just to get them on board with doing research at all! Most of them do not possess the information literacy skills necessary to distinguish popular sources from scholarly sources, and I spend a great deal of time during the course of any given semester trying to teach them how to determine the credibility of information. These are the same people who make mistakes within the LMS discussion threads and rather than go back and edit or amend their work they send personal messages to me imploring me to erase their comments because they are embarrassed over what is essentially their own learning process! If I unleashed them into the global community of online information with full editing rights and an assignment to contribute to a live wiki, they’d have to exhibit a considerable increase of investment. They’d have to produce real content. They’d have to do GENUINE research because they’d certainly be corrected quickly enough by other contributors. They wouldn’t have a safety net, you know. They’d be held to a much higher standard of accountability, and it’d be … .” My voice trailed off. (Insert  “It’d be … beautiful!” I realized, with a twinkle in my eye. (Cue theme music from

“It’d be … beautiful!” I realized, with a twinkle in my eye. (Cue theme music from

My favorite aspect of this interview is the love of teaching and learning that Lauren and I share. I also must acknowledge the empowering support we provide to each other, as evidenced in our mutual positive regard both in this podcast and in real life. I feel this is an important aspect to note because professional women can often become highly competitive in the workplace, and by doing so can stifle and alienate their colleagues. (Both Lauren and I have experienced that kind of negativity in the past.) When we adopt a collaborative mindset in which we nurture and respect our unique gifts and talents while also learning to embrace a shared mission – we can accomplish truly great things.

My favorite aspect of this interview is the love of teaching and learning that Lauren and I share. I also must acknowledge the empowering support we provide to each other, as evidenced in our mutual positive regard both in this podcast and in real life. I feel this is an important aspect to note because professional women can often become highly competitive in the workplace, and by doing so can stifle and alienate their colleagues. (Both Lauren and I have experienced that kind of negativity in the past.) When we adopt a collaborative mindset in which we nurture and respect our unique gifts and talents while also learning to embrace a shared mission – we can accomplish truly great things. Reflection: Podcasting presents challenges I did not expect! I produced 28 minutes of content and had to edit judiciously in order to yield a final product somewhere close to the target length of 10 minutes. Sound editing is a meticulous process and proved somewhat time consuming for me (I acknowledge this could be attributable in part to my own recent health setbacks). Another challenge I experienced was my great feeling of urgency to keep the interview moving while simultaneously enunciating with precision, trying to relax, and proceeding primarily unscripted. With the exception of providing Lauren a short list of questions to anticipate, I performed absolutely no advance preparation for the interview – there was no coaching my interviewee nor compelling her to respond in any certain manner. We spoke briefly and generally about my LDT courses and why I’d decided to pursue another advanced degree, and then I simply began recording with Audacity. While I appreciate the authenticity of the approach I took, in retrospect I would slow down and deal with dead air space in order to create content a bit more easily editable. However, all things considered – as a first experience with podcasting this assignment proved itself awesome, and I am looking forward to doing it again!

Reflection: Podcasting presents challenges I did not expect! I produced 28 minutes of content and had to edit judiciously in order to yield a final product somewhere close to the target length of 10 minutes. Sound editing is a meticulous process and proved somewhat time consuming for me (I acknowledge this could be attributable in part to my own recent health setbacks). Another challenge I experienced was my great feeling of urgency to keep the interview moving while simultaneously enunciating with precision, trying to relax, and proceeding primarily unscripted. With the exception of providing Lauren a short list of questions to anticipate, I performed absolutely no advance preparation for the interview – there was no coaching my interviewee nor compelling her to respond in any certain manner. We spoke briefly and generally about my LDT courses and why I’d decided to pursue another advanced degree, and then I simply began recording with Audacity. While I appreciate the authenticity of the approach I took, in retrospect I would slow down and deal with dead air space in order to create content a bit more easily editable. However, all things considered – as a first experience with podcasting this assignment proved itself awesome, and I am looking forward to doing it again!

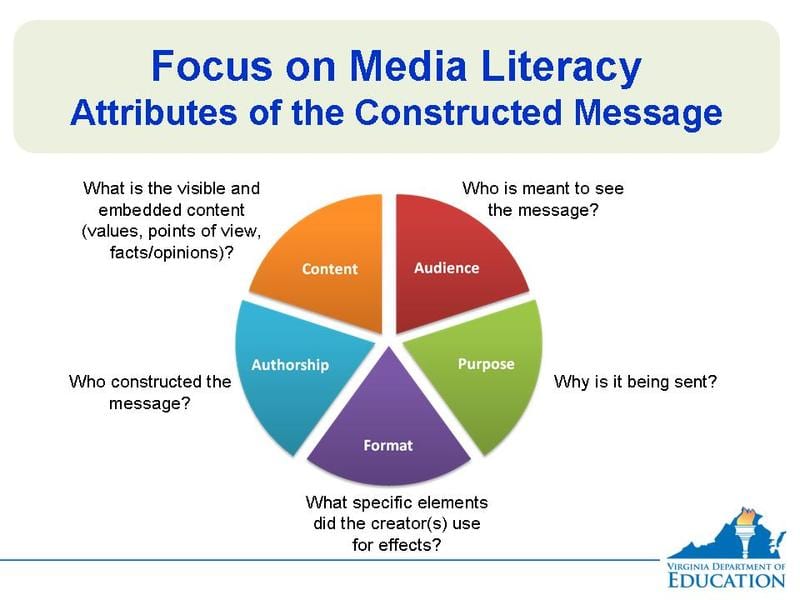

Our collective theme for blogging this week resounded in the challenges media literacy instruction presents to both teachers and learners, and in constructing interventions to address those difficulties. Interestingly, while we all opted to work with the Buckingham article, it resonated with each of us a little differently. In general, however, the issue of source credibility and its relationship to prerequisite critical thinking skills ranked high on our collective problem-solving agenda.

Our collective theme for blogging this week resounded in the challenges media literacy instruction presents to both teachers and learners, and in constructing interventions to address those difficulties. Interestingly, while we all opted to work with the Buckingham article, it resonated with each of us a little differently. In general, however, the issue of source credibility and its relationship to prerequisite critical thinking skills ranked high on our collective problem-solving agenda. “Similar to this graphic organization of web resources,” Justice proposes, “the periodic table is associated with ordering known elements into a system. In the future, I hope media literacy can be taught in such a way that people will immediately associate media elements with the instantly recognizable periodic chart. Imagine your digital literacy as it conforms with these organized columns. Are there elements missing, resources that you think are essential which deserve being petitioned to join?”

“Similar to this graphic organization of web resources,” Justice proposes, “the periodic table is associated with ordering known elements into a system. In the future, I hope media literacy can be taught in such a way that people will immediately associate media elements with the instantly recognizable periodic chart. Imagine your digital literacy as it conforms with these organized columns. Are there elements missing, resources that you think are essential which deserve being petitioned to join?”

Empowering learners by encouraging critical thinking comprises an important interventional role. “An important piece to address when teaching digital media literacy,”

Empowering learners by encouraging critical thinking comprises an important interventional role. “An important piece to address when teaching digital media literacy,”