So far I have really only discussed how chord progressions entrance our ear, but using some of the same logic behind chord progressions, we can see that the melodies of some songs are a bit more thought out then we first believed. I will admit, when Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling” came out, I was addicted to it, as were most people. So much so that I asked my saxophone private lessons teacher to obtain a copy of the music so I could play it for myself.

Source: IMDB

When I later received the music, I was caught off guard by the fact it was written almost entirely with two notes, an A and a G. In the key of G, the A is the second note of the scale, which is known as the semitonic, and obviously the first note of the scale, the G, is the tonic. At first I thought the music was just too simple and stupid. After all, even I could write a song with just two notes, but the key was the A in the melody. If you take a listen to the song, you will notice that when Timberlake sings the chorus “Nothing I can see…you when…dance dance dance” all these words are on the same note, the semitonic A. The ones I omitted, but and you, are closely related on the tonic of the scale and add a brief resolution. However, this semitonic note is so crucial in the chorus because it allows our ear to tune into the note right above the tonic where we want to be. By building a minute amount of tension with the note above the tonic, we want to keep listening to hear the phrase resolve.

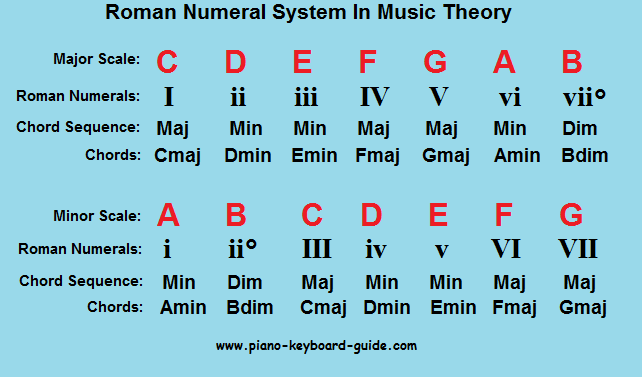

But the theory behind staying on the second note of a scale goes a bit deeper. In every chord in a major key, the second note of the chord fits in a musically sound manner. Though it would take too long to show every combination of the second note and how it fits into a chord, choosing the semitonic as the note to write a melody around is a safe choice since it will fit into nearly any chord progression. Therefore, combining a semitonic based melody and an addicting progression will make your song irresistible, and is seen in many recent pop hits like Taylor Swift’s “I Don’t Want To Live Forever” and the Weekend’s “I Can’t Feel My Face”. Because of this example of melodical music writing, it is easy to see that even a musically simple song that utilizes primarily two notes can be addicting to our ears if the song writer knows what they are doing.