When contemplating the meaning of a “feminist artist,” there are many aspects to consider, from their contribution to the political movement of second-wave feminism to the style of artwork they created to the relevance of their work and how it applies to today.

It can be argued that the most influential feminist artwork is timeless, with themes that transcend the period in which it originated, and correlate to the struggles and collective experiences of women across generations. Feminist art is often hard to digest or unsettling because of its multiple layers and implications, ranging across social, political, and sexual vectors. This “unsettling” nature is necessary because real change is never comfortable.

After defining this idea of the “feminist artist” and certain criteria inherently present in the label, in this blog I would like to reflect on the work of Barbara Kruger and her role as one of the most engaging and interesting feminist artist in modern times.

/Barbara-Kruger-GettyImages-523987759x1-57367ec63df78c6bb0bed99a.png)

Kruger’s dive into conceptual feminist art took place in the 1980s and 90s, through the medium of her signature style of work. One of her most famous pieces was created in 1989 and features a black and white close-up image of a woman’s face, split evenly down the middle into positive and negative exposures. Imposed over her face, in red and white ink, are the words “Your body is a battleground.”

This piece was produced for the March on Washington and served to support reproductive freedom. This is an example of one of Kruger’s deeply feminist pieces because it not only sheds light on the objectification of women under the male gaze, but also provides commentary and connects to the deeper societal and feminist issue of abortion and reproductive rights.

Though her work may seem simplistic, it is a testament to her artistic skills and vision that she is able to explore themes of sexualization, objectification, and women’s rights all using only five words.

Another interesting aspect affecting the themes of Kruger’s work is a byproduct of the age and kairotic moment in which she began to produce her work.

Kruger developed her signature style in the midst of the consumer culture craze in the United States, which was brought on by an effort to prove democratic capitalism is superior to Soviet communism . As a result, themes of consumerism, individualism, and power are all also present in Kruger’s work.

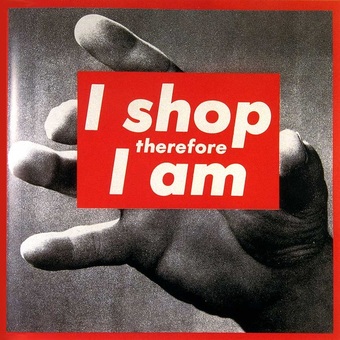

This is evidenced in her 1990 piece featuring the words “I shop therefore I am,” which is a play on the French philosopher Descartes famous phrase, “I think Therefore I am.”

With this cheeky jab, Kruger draws awareness to the rampant consumer culture dominating the nation and its negative affects on concepts such as identity and power. Here, Kruger demonstrates how American’s identity is now becoming wrapped up in what they buy and own, and materialistic pleasures take precedence over actual thought and individuality.

Barbara Kruger can indisputably be considered a feminist artist due to the wide range of themes embedded in her work that challenge unfair body politics, reproductive rights, the male gaze and female objectification, and the general silencing of the voices of women in society.

Not only that, but Kruger’s work takes on an activist impetus by incorporating themes such as consumerism, individualism, and power that indirectly affect feminism, but also hold merit on their own.