Introduction

The Asian identity is usually regarded as a race that includes individuals of Asian descent who are characterized by certain physiological features, such as: eye shape, skin tone, and hair texture, and so forth. However, Ono and Pham (2009) affirmed that the Asian American identity is one that is self-defined, meant to distinguish a cultural group of individuals from varying Asian countries living in the United States. Thus, the Asian American identity includes a variety of distinct cultural practices and traditions as well. However, in media, this differentiation is often not emphasized or acknowledged. Patton (2001) asserted the Asian Americans are often “trapped and controlled by stereotypical and marginalizing representations (206). This is especially harmful concerning the underrepresentation of Asian Americans in media (Mok 1998).

“The Dragon Lady” stereotype initially originated from a Western perspective, inspired by the female villain in the Terry and the Pirates comic strips, who was later portrayed by the Asian actress, Anna May Wong. The character first appeared in 1934, and the term “dragon lady” was first used around 1935. However, it is also closely tied to the first Asian American stereotype, “yellow peril,” which was born out of the threat of Asian invasion in the western territories during the 1300s (Hoppenstead 286). In some ways, “The Dragon Lady” stereotype is a modification of the “yellow peril” stereotype into a more “deviant, sexualized” female version (287). Although the term is not exclusively limited to describing Asian women, it is most commonly associated as an East Asian stereotype, and continues to be perpetrated in popular culture as one.

“The Dragon Lady” trope carries with it a negative connotation due to its origins as a villainous character, and Asian women portrayed as “dragon ladies” are usually: deceitful, domineering, cold, calculating, abrasive, and mysterious. Moreover, this stereotype is often oversexualized, with “dragon ladies” frequently using their sexuality as a power, seducing men in order to further their own agendas and goals.

Historically, the term is commonly associated with Asian women in positions of power, such as: Soon Mei-Ling (Chiang Kai-Shek’s wife), Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu, Empress Dowager Cixi. Nowadays, the term is commonly used to describe Asian American characters in film or television that are career-oriented and in high-ranking positions in their respective professional fields.

Orientalism

In Edward Said’s 1978 text, Orientalism, Said put forth the concept of orientalism, or rather, how the West constructed an erroneous representation of the East. Said asserted that the West constructed the East as an “other,” labeling it the “orient” through arbitrarily demarcating the differences between the Occident and the Orient, characterizing the Orient as irrational, feminine, and weak in order to make the East seem less threatening and the West superior. Moreover, this characterization is also often used in defense of imperialism, reinforcing a binary opposition that allows for the continued perpetration of the negative stereotypes surrounding the East and allows for the continued subjugation of the East. Said contends that “Orientalism: is a dynamic process, susceptible to the changing political and social context. As such, although “Orientalism” is commonly used today to explain the negative connotations associated with the Middle East, the concept is nonetheless applicable to the Western view of East and South Asian, and provides important context to the development of the “Dragon Lady” stereotype that this archive seeks to examine, and, on a broader scale, how the stereotype reflects on the current Western view and interpretation of Asian Americans.

Cristina Yang

Sandra Oh’s portrayal of Dr. Cristina Yang is particularly important given how popular Grey’s Anatomy is. In 2007 the show won a Golden Globe Award for “Best Television Series,” and, for each year since 2005, the show has received an Emmy Award nomination. Oh has also received several awards for her portrayal of Dr. Cristina Yang, including a Golden Globe award and a Screen Actor’s Guild award. As such, the Asian American stereotypes perpetrated in Grey’s Anatomy take on special importance since the show has been viewed by such a broad audience. Although there are certainly many instances where Yang also displays compassion and a deep loyalty to those that she cares about, Yang nonetheless is known for this type ruthless determination. In fact, throughout the show it is often implied that her career success is attributed to the fact that she can seemingly wholeheartedly distance her personal feelings to her career decisions.

In this scene, Yang, in a moment of panic, offers to “trade” her significant other, Dr. Owen Hunt, in exchange for Dr. Theodora “Teddy” Altman’s continued mentorship. Dr. Altman is the new attending cardiothoracic surgeon at Seattle Grace Teaching Hospital; however, her feelings towards her resident, Cristina Yang, are complicated by her romantic feelings for Yang’s boyfriend, Dr. Hunt. When attempting to convince Dr. Altman to stay, Cristina chases after her and offers up a variety of incentives, including more money for research and a better lab, which is evidence of Cristina’s desire and ability to achieve her own goals throughout whatever means possible. When it is revealed that the only thing Dr. Altman wants is Cristina’s boyfriend, Dr. Hunt, Yang says, “Fine! Done! Take him!” Although Yang blurts out this proposition in a moment of frenzy, shocking both her and Dr. Altman with her offer, it is nonetheless evidence of Yang’s priorities. Cristina appears to look guilty and ashamed after her outburst, but she does not revoke her offer. Although Yang ostensibly loves Dr. Hunt and later agrees to marry him, under pressure, it seems Yang will still chooses her career over her significant other. This furthers the “dragon lady” stereotype depicting East Asian American woman as cold and calculating, willing to use their sexuality to further their own motives, uncaring of how their actions may affect others. This scene also portrays Yang as someone who treats people, even her loved ones, as objects. It makes viewers believe that Yang has very transactional relationships. In some ways, this is just a continuation of the behavior she has exhibited her whole life towards sexuality and power. Previously, Cristina had admitted to sleeping with her former professor, ostensibly for his mentorship, as he too was a very talented surgeon. Thus, on a specious level, Cristina’s character is built from the “dragon lady” stereotype, thereby playing into the Asian American tropes that are continually perpetrated in regards to Asian American media representation.

Sandra Oh’s portrayal of Dr. Cristina Yang is particularly important given how popular Grey’s Anatomy is. In 2007 the show won a Golden Globe Award for “Best Television Series,” and,for each year since 2005, the show has received an Emmy Award nomination. Oh has also received several awards for her portrayal of Dr. Cristina Yang, including a Golden Globe award and a Screen Actor’s Guild award. As such, the Asian American stereotypes perpetrated in Grey’s Anatomy take on special importance since the show has been viewed by such a broad audience. Although there are certainly many instances where Yang also displays compassion and a deep loyalty to those that she cares about, Yang nonetheless is known for this type ruthless determination. In fact, throughout the show it is often implied that her career success is attributed to the fact that she can seemingly wholeheartedly distance her personal feelings to her career decisions.

In many ways, Dr. Cristina Yang can be viewed as the paragon of success that many Asian families hope their children will aspire to be. In Women Warrior, author and narrator Maxine Hong Kingston, speaks at length about her convoluted relationship with her mother and the expectations she was subjected to as a first generation immigrant. Dr. Cristina Yang is perhaps the archetype of success that Kingston feels her mother, Brave Orchid, wanted her to pursue in the future. The type of woman that is strong and fearless, able to separate her emotional desires from her work objects. In one scene, the Brave Orchid asks her daughter, “I don’t see why you can’t be a doctor like me?” (Kingston 202). Although Kingston achieves a variety of successes in her personal and professional life, her mother’s constant nagging and criticism are a point of contention between mother and daughter and, for Kingston, seem to represent her mother’s critical nature and inability to accept anything less than perfect from Kingston.

However, the mother also displays a dragon lady instinct herself when she is trying to persuade her own sister, known as Moon Orchid, to confront her husband who had abandoned her in China in order to marry another wife and begin a new life. She tells Moon Orchid,

You have to ask him why he didn’t come home. Why he turned into a barbarian. Make him feel bad about leaving his mother and father. Scare him. Walk right into his house with your suitcases and boxes. Move right into the bedroom. Throw her stuff out of the drawers and put yours in. Say, ‘I am the first wife, and she is our servant’” (Kingston 126).

Here, the mother advocates not only for an aggressive approach, telling her sister to move right in and physically remove the second wife’s belongings from the house, but she also tries to persuade the sister to emotionally manipulate her husband, guilting him into feeling bad so that her sister may establish her dominance from the very beginning, treating the second wife as a “servant.” In essence, not only is the mother displaying a domineering, “dragon lady” personality in this scene-indicating that she is willing to use both emotional and physical manipulation to achieve her goals-she is also trying to persuade her sister to become a “dragon lady,” as well, which continues to create a long succession of “dragon ladies” for the family.

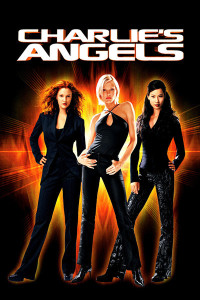

Alex Munday

Alex Munday, portrayed by Lucy Liu in the Charlie’s Angels (2000, Joseph McGinty Nichol) film series, is another revealing example of the “dragon lady” stereotype prevalent in American media. However, in contrast to Cristina Yang, Munday’s character displays the hypersexualization of Asian-American women in media. Out of the three “angels,” Munday is the only Asian-American character and, on her “Charlie’s Angels Wikia” page, she is described as “a sophisticated class act, with dark brown eyes and never a hair out of place,” who works as an “exotic private investigator,” and is “the businesswoman” of the trio. Munday’s character is distinguished as “the most diverse angel by far” and is known to speak multiple languages. Her parents were both Harvard professors, but, at 13 her intelligence had already “eclipsed her parents’” and she received the remainder of her education overseas, where she trained as an Olympic gymnast and became a chess prodigy, skilled fencer, horseman, and ballerina. Aside from being a private investigator, Munday also apparently studied medicine, and worked for NASA as an on-call consultant.

Like Cristina Yang, Alex Munday is shown as extremely competent and skilled, a “jack of all trades,” in a sense. Her long list of skills and accomplishments helps establish her as the quintessential, overachieving “Asian” stereotype that Cristina Yang is regarded with as well. However, in contrast to Yang, Munday is subjected to a type of hypersexualization that comes to define her career as an “angel” as much as her intelligence does. “Dragon ladies” are known to use their sexuality in order to further their personal interest. In this clip shown above, Munday is tasked with distracting the roomful of computer scientists so that her team members may infiltrate a secure area. In order to distract the men, Munday dons a tight, black leather suit that is not only revealing but also gives off a dangerous air, thereby giving Munday’s sexuality a threatening edge that is common for the “dragon lady” trope. As much as Munday is a sex symbol in this scene, she also is resolutely in control of her sexuality, using it in a calculating manner in order to pursue her goals.

The whip that Munday carries with her is evidence of this rougher, domineering edge that is a hallmark of the “dragon lady” trope. Munday is seen alternating between being gentle with the men (caressing them and speaking in slow, husky tones with them) and threatening them, and central theme in the “dragon lady” stereotype is this sexual duality. At times “dragon ladies” may seem docile and sexually submissive; however, they are very much aware of the effect they have on men and use it to their advantage, shifting the quality of their sexuality in order to achieve their goals.

In essence, Alex Munday’s character becomes a caricature of East Asian women, portraying a one-dimensional perspective of the transactional nature of Asian women. In Charlie’s Angels, Alex Munday is integral to the team because of her intellect, skill, and sexuality; however, very little attention is paid to her personality, and she is never praised for her compassion, empathy or kindness, but rather her cold, calculating attributes are emphasized. In The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene by Celine Parreñas Shimizu, Shimizu asserts that

“the particular sexual subjection for the Asian woman occurs at two levels. First, the Asian Femme Fatale’s sexual subject in film involves an inherently different sexuality reduced to race and culture. That is, her sexuality is ascribed as natural to her particular raced and gendered ontology” (66).

For Alex Munday, she is naturally seen as a dominatrix due to her Asian heritage, and out of the three Angels she is the one tasked with distracting the men. Thus, at the same time, Alex Munday’s sexual portrayal also creates a binary opposition between her, the Asian character, and her teammates, the white characters. Shimizu asserts that the second level of sexual subjection for the Asian woman is that it is

“framed in a rivalry with a White woman’s, in terms of competing for idealized heterosexual femininity” (66).

In Alex Munday’s case, this is evident through the fact that out of all the Angels, Munday is the one that is used to lure the men away so the Angels may execute their goal.

Alex Munday’s character is thus comparable to the female Asian characters in Peter Bacho’s Dark Blue Suit. In particular Stephie, an Asian American character is shown using her sexuality for power as well. She uses her great beauty in order to marry someone wealthy, thus transcending her own poor upbringing. Although she is in love with Buddy, the protagonist, she chooses to marry

a law student at Northwestern on a summer internship…white guy whose folks had money because she knows that she will have a more comfortable life with him (Bacho 116).

Thus, Stephie’s sexuality allows her the means to create a better life for herself, and in that way, it seems be emphasized as her greatest asset, one that her mother convinces her she should capitalize on by

grab[bing] some rich guy and lie to him, tell him [she] was Spanish, Hawaiian, anything….back then [she] heard it all the time: Use your looks, flutter those eyes. (121)

advice which Stephie ends up following, emphasizing how Stephie uses her sexuality for transactional purposes

Once she settles into the marriage, she becomes unhappy and tells Buddy that

after two years of [her husband’s] crap, I shut him out. Cold. First, I stuck him in the spare room, then I started sleeping in flannels. Thick, ugly ones. You know, the kid kind with boots…try getting some through that (117).

For Stephie, her “affection” towards her husband is only ephemeral, corresponding to what and when she needs him. However, once she is married to him and has access to a better life, she discards him, and

got [herself] the best asshole divorce lawyer his money could buy. By the time it was over, [she] almost felt sorry for my ex, but not enough to give him back this townhouse and that nice chunk of settlement cash (117).

The caustic way in which Stephie recounts her ruthless divorce with her husband is indicative of the cold-heartedness that the “dragon lady” stereotype is represented with; moreover, Stephie’s whole description of her relationship with her husband is devoid of any emotion, making it clear that the whole process was more or less transactional for her. Later, when she visits Buddy, she seduces him-again using her sexuality-even though he is married. She displays a resolute determination to get what she wants no matter the cost to his marriage because she is thinking about her own desire. In fact, in order to seduce him, she even brazenly

pull[s]…on [his wedding] ring, which smoothly slid off, before she examined the band, then threw it to a far corner of the room.

Stephie seems to be claiming Buddy as “hers” by physically removing any evidence of his marriage from his body, which emphasizes her desire to be in control. Her desire for control, her ruthless determination, and her ability to use her sexuality for transitional purposes add up to create one dimension of the “dragon lady” stereotype that Stephie exhibits throughout the Dark Blue Suit.

Similarly, in Anil’s Ghost by Michael Ondaatje, Anil displays a willingness to use her sexuality in a transactional format as well. She states that She knew herself to be, and was known to others as, a determined creature (67). For instance, her name had not always been Anil, but at 12, she became intent on changing her name to Anil, which was previously her brother’s name. Eventually the children worked out a trade and,

she gave her brother one hundred save rupees, a pen he had been eyeing for some time, a tin of fifty Gold Leaf cigarettes she had found, and a sexual favour he had demanded in the last hours of the impasse (67-68).

Anil exhibits an almost shocking willingness to do whatever it takes to get what she wants. She is not only shrewd enough to offer her brother the monetary physical objects she knows he has been eyeing, but she is also willing to offer up her body for the name, and this calculating, determined nature is indicative of a “dragon lady” aspect to Anil’s personality. Furthermore, when recalling the whole incident, she does not seem to be perturbed or regretful at the taboo nature of the act, but rather says that,

“later when she recalled her childhood, it was the hunger of not having the name and the joy of getting it that she remembered most…Twenty years later she felt the same about it. She’d hunted down the desired name like a specific lover she had seen and wanted, tempted by nothing else along the way” (68).

Even at 12, Anil had displayed a startlingly precise ability to separate her personal emotions from her long-term goals, working purposefully and resolutely to achieve what she wanted, no matter the physical or emotional cost, just as a “dragon lady” would.

Bibliography [Introduction]

Patton, T. (2001) Ally McBeal and her homies: The reification of white stereotypes of the other. Journal of Black Studies, 32, 229-260

Jones, Norma B. Beyond Suzie Wong? An Analysis of Sandra Oh’s Portrayal in Grey’s Anatomy. Thesis. University of North Texas, 2011. Denton: U of North Texas, 2011. Print.

Hoppenstand, Gary. “Yellow devil doctors and opium dens: The yellow peril stereotype in mass media entertainment.” Popular culture: An introductory text (1992): 277-91.

Bibliography [Orientalism]

Said, Edward. “Orientalism. 1978.” New York: Vintage 1994 (1979).

Bibliography [Cristina Yang]

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The woman warrior: Memoirs of a girlhood among ghosts. Vintage, 2010.

Rhimes, S. (Writer), & Corn, R. (Director. (2009) Blink [Television Series Episode]. In B. Beers, M. Gordon, J. Parriot, & S. Rhimes (Executive Producer), Grey’s Anatomy. Los Angeles, CA: American Broadcast Company

Bibliography [Alex Munday]

Bacho, Peter. Dark Blue Suit and Other Stories. Seattle: U of Washington, 1997. Print.

Charlie’s Angels. Dir. Joseph McGinty Nichol. Perf. Lucy Liu, Drew Barrymore, Cameron Diaz. Columbia Pictures Corporation, 2000. Film.

Miller-Young, Mireille. “Hip-hop honeys and da hustlaz: Black sexualities in the new hip-hop pornography.” Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism8.1 (2008): 261-292.

Ondaatje, Michael. Anil’s Ghost. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000. Print.