Development of the Dragon Lady stereotype from Milton Caniff’s original comic strip Terry and the Pirates to the strip’s brief revival in the mid-1990s.

Caniff’s Comic

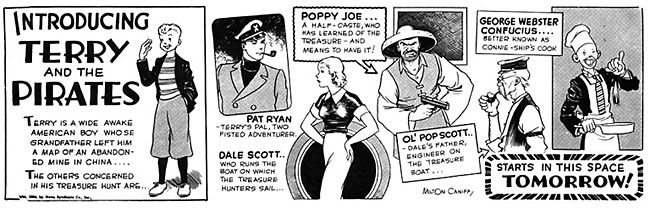

Terry and the Pirates was an action-adventure comic strip created by cartoonist Milton Caniff. Captain Joseph Patterson, editor for the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate, had admired Caniff’s work on the children’s adventure strip Dickie Dare and hired him to create the Terry and the Pirates. The daily strip began October 22, 1934, and the Sunday color pages began December 9, 1934. Initially, the storylines of the daily strips and Sunday pages were different, but on August 26, 1936, they merged into a single storyline. The strip was read by 31 million newspaper subscribers between 1934 and 1946. In 1946, Caniff won the first Cartoonist of the Year Award from the National Cartoonists Society for his work on Terry and the Pirates.

Terry and the Pirates was an action-adventure comic strip created by cartoonist Milton Caniff. Captain Joseph Patterson, editor for the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate, had admired Caniff’s work on the children’s adventure strip Dickie Dare and hired him to create the Terry and the Pirates. The daily strip began October 22, 1934, and the Sunday color pages began December 9, 1934. Initially, the storylines of the daily strips and Sunday pages were different, but on August 26, 1936, they merged into a single storyline. The strip was read by 31 million newspaper subscribers between 1934 and 1946. In 1946, Caniff won the first Cartoonist of the Year Award from the National Cartoonists Society for his work on Terry and the Pirates.

In addition to providing the source for the dragon lady stereotype, Caniff’s strip is interesting, in relation to our class, in two other primary ways. The first is in comparison to Okubo’s usage of drawn images in depicting the internment of the Japanese during World War II in Citizen 13660. It’s fascinating to think about both collections of drawings being created contemporaneously and concurrently. The second is a passing idea I had when I read the first comic in the Terry and the Pirates series reproduced above. In the bottom right hand corner, Caniff alerts the reader that Terry and the Pirates “starts in the space tomorrow.” I hadn’t thought of the print form, in this case a newspaper, in its physicality as a usage and assertion of space. In terms of archiving, print materials are effected by inclusion and exclusion. When Terry and the Pirates filled this space, it occupied the space in the newspaper and by default excluded other materials that could have been printed. It leads me to question how a common print form, let’s say newspaper funnies, interacts with people politically, personally, culturally, and to what degree. This comic became an iconic cultural piece, the origin of the dragon lady stereotype, and as several of my photos demonstrate, certainly lifted from the pages of newspapers in interesting ways.

The Dragon Lady, aka Madame Deal

The Dragon Lady is described as a beautiful but cold pirate queen who clashes with Terry and Pat continuously. Mirroring contemporary political and military events including the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II, Caniff placed his comics in contemporary settings and scenarios. In the strip, as the Japanese invade China, The Dragon Lady becomes a resistance leader, attacking Japanese forces, making it clear it is not out of patriotism but wanting to keep her riches intact. It is hinted she is in love with Pat, but she is unwilling to give up her empire for him. After the war ends, she returns to criminal activities. Caniff included a number of non-American female antagonists, all of whom refer to themselves in the third person. These included The Dragon Lady herself and other female criminal and spy characters. Any power or danger these character possess is often tempered through their awkward, ridiculous dialogue. As demonstrated in the image above, “Yoho and a bucket o’ yak butter” seems to take the edge off of The Dragon Lady’s blade and her threats of a prolonged and painful death. There is also a distinct separation between The Dragon Lady and western femininity, as seen in the excerpt below.

As stated The Dragon Lady (confusing because of her third person self reference), there is a clear separation between west and east. In this panel, it is unclear as to what qualities are being attributed to The Dragon Lady, and are even seemingly paradoxical. It is a strange assertion of Foucault’s “other,” perverse in that the non-white character is the aggressor in asserting a fundamental “otherness” to her white counterpart. Not to mention, if The Dragon Lady possesses opposite qualities, is the assertion that she is “feminine” or something else? At least “now we may laugh…”

This following frame drops the consideration of femininity, and instead reiterates The Dragon Lady’s primary, goal orientated, quality. Western “sacrifice and patriotism” is the opposite of the “oriental,” characterized as “realistic.” Initiating a mystic superiority, the American woman is told that The Dragon Woman will, “if she must, sacrifice herself” because the Asian characters are “old and wise.” Go figure, they look the same to me.

Other Versions

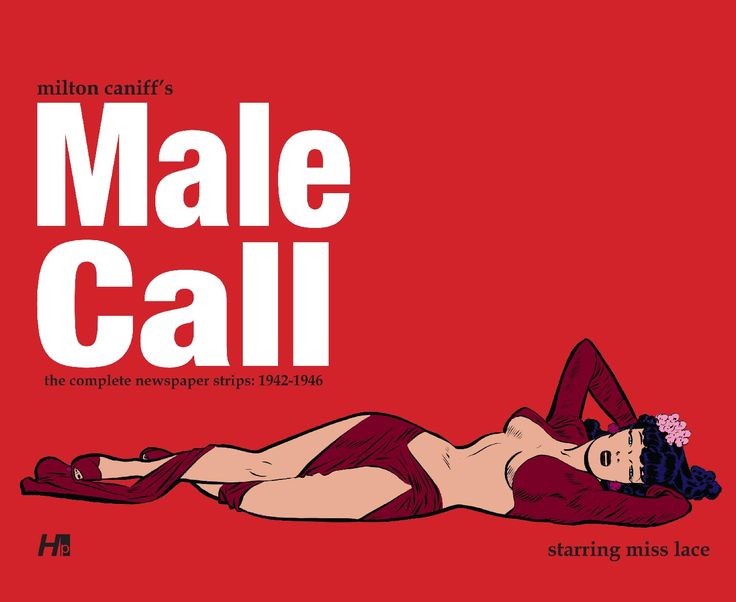

Interestingly, Caniff’s comic was reproduced in several separate forms. The first was the free version of Terry and the Pirates Caniff donated to the military, printed in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes. The strip was racier than the regular strip, and complaints caused Caniff to rename it Male Call to avoid confusion until the strip was discontinued in 1946.

In this context, Caniff’s comic inspired the soldiers to reproduce the Dragon Lady, and other characters, in paintings and markings on their military equipment and vehicles. The curious thing is that The Dragon Lady doesn’t appear in this comic strip. Instead, The Dragon Lady is replaced with the female character pictured above, Miss Lace. Nonetheless, soldiers reproduced The Dragon Lady as seen in the following images.

The Dragon Lady’s identity is reduced to her sexuality. These reproductions do not depict her as cunning, threatening, or violent as she had been previously. In place of her weapons and scowl is less clothing. Far less clothing… These iterations point toward the sexualization of the Dragon Lady stereotype.

Wunder’s Version

After Caniff left the strip in 1946, Terry and the Pirates became a “dead strip,” reprinting previous issues until it was assigned to Associated Press artist George Wunder. Wunder drew highly detailed panels, but some critics claimed that it was sometimes difficult to tell one character from another and that his work lacked Caniff’s essential humor. Nevertheless, he kept the strip going for another 27 years until its discontinuation on February 25, 1973. In Wunder’s version, he maintains The Dragon Lady’s role as an aggressive, sexualized, dangerous figure, as seen in Wunder’s drawing on this envelope. More importantly is the removal of The Dragon Lady from the comic strip, inserted here for the sake of comedy, indicating the degree to which the comic, and specifically The Dragon Lady, became a part of American culture and a root perception of Asian women. As indicated in Sabrina’s post containing more contemporary examples, the Dragon Lady stereotype remains a part of American culture and perception.

Revival

The strip was revived in the 1990s for a very short period of time, until its final demise on July 27, 1997. On March 26, 1995, the Brothers Hildebrandt revived and updated Terry and the Pirates under the direction of Michael Uslan. In the revival, though I can’t find issues or even copies of frames for myself, The Dragon Lady is described as a Vietnam War orphan. If this is true, it reinforces the interchangeability of “Asians” under one diasporic umbrella. Chinese is interchangeable with Vietnamese, WWII and Vietnam are naturalized justifications for the inclusion of Asian women, and the drawn form is a medium capable of presenting both. From an American perspective, war becomes a driving force for the inclusion of Asian women, similar to the conception of war as a driving force of migration and therefore the creation (or destruction) of migrant archives.

I would argue that war served a symbolic-cultural migratory role in the United States, importing an Americanized perception or depiction of Asian women into American culture. As indicated in Sabrina’s examples, Caniff’s Dragon Lady and her primary qualities played a significant role in shaping perceptions of Asian-American women, as demonstrated by the examples of dragon ladies in contemporary film and TV.

Works Cited

Caniff, Milton Arthur (1975). Enter the Dragon Lady: From the 1936 classic newspaper adventure strip (The Golden age of the comics). Escondido, California: Nostalgia Press. (PDF).

Menon, Elizabeth K. (2006). Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale. Asian American Experience. University of Illinois Press.

Okubo, Miné, and Christine Hong. Citizen 13660. Seattle: U of Washington, 2014. Print.

Prasso, Sheridan (2005). The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, & Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. New York: Public Affairs. (PDF)

Asian American Feminism

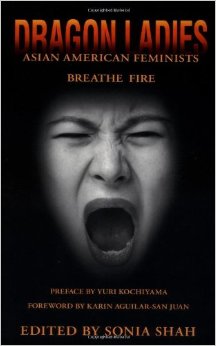

Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists Breathe Fire

This final item is presented as a primary text in examining the dragon lady stereotype. In brevity, both because we’ve written so much already (more than four) and, fittingly, because I didn’t have time to read the book, Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists Breathe Fire is a collection of 16 critical essays by Asian American writers, artists and activists first published in 1997. Divided into four parts: Strategies and Visions; An Agenda for Change; Global Perspectives; and Awakening to Power. The book presents the views of a number of Asian women on feminism, often describing their frustration with the mainstream feminist movement in the United States which is seen to be dominated by white women. The collection also contains a number of interviews.

Edited by Sonia Shah, the work contains a preface by Yuri Kochiyama and a foreword by Karin Aguilar-San Juan. It sets out to “describe, expand, and nurture the growing resistance of Asian American women and girls and their allies” by bringing together the reactions of female Asian Americans. Shah sees the work as contributing to an understanding of “a growing social movement and an emerging way of looking at the world” resulting from racism and patriarchy in American society and as well as U.S. aggression against Asia.

In the context of the origins of the stereotype and the contemporary usages Sabrina presented, the reappropriation of the negative stereotype “dragon lady,” carries several connotations. By adopting the negative phrase, there is a degree to which the authors and contributors disarm the phrase as a weapon, taking away any venom it might carry by asserting, perhaps sarcastically, that they are not only dragon women, but are actively and aggressively forwarding their thoughts and agendas (breathing fire). That said, in light of the contemporary examples Sabrina presented and our conversation wherein no one could name an example of a film or show that presented an Asian woman devoid of stereotypical qualities, it is clear that at least in terms of popular or entertainment culture, fire breathing or not, dragon ladies are still ingrained in these perceptions.

Works Cited

Chung Simpson, Caroline. “Reviewed Works: Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists. 2001

Shah, Sonia. Dragon Ladies: Asian American Feminists Breathe Fire. South End Press. 1997