If you’ve been following up until this point, you have amassed a significant amount of knowledge about harmony–more specifically, chords, their function, and their notation. Now, we can begin to explore how these chords are actually used in music. Let’s take a look at some common chord progressions.

Perhaps the most famous chord progression, the I-V-vi-VI has been used across the decades in many different genres. Some examples include “Let It Be” by the Beatles, “Don’t Stop Believin” by Journey, “Take On Me” by Aha, and “I’m Yours” by Jason Mraz.

While this particular order tends to be popular, the I, V, vi, and VI chords are often rearranged. In the ’50s and early ’60s, the I-vi-IV-V progression was especially popular. An example is “Those Magic Changes” by Sha Na Na.

Another popular variation is iv-IV-I-V, as heard in “Otherside” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers and “Not Afraid” by Eminem.

Some songs don’t even bother with the vi chord. I-IV-V is another very popular progression. Some examples include “La Bamba” by Ritchie Valens, “Louie Louie” by the Kingsmen, and “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by the Clash.

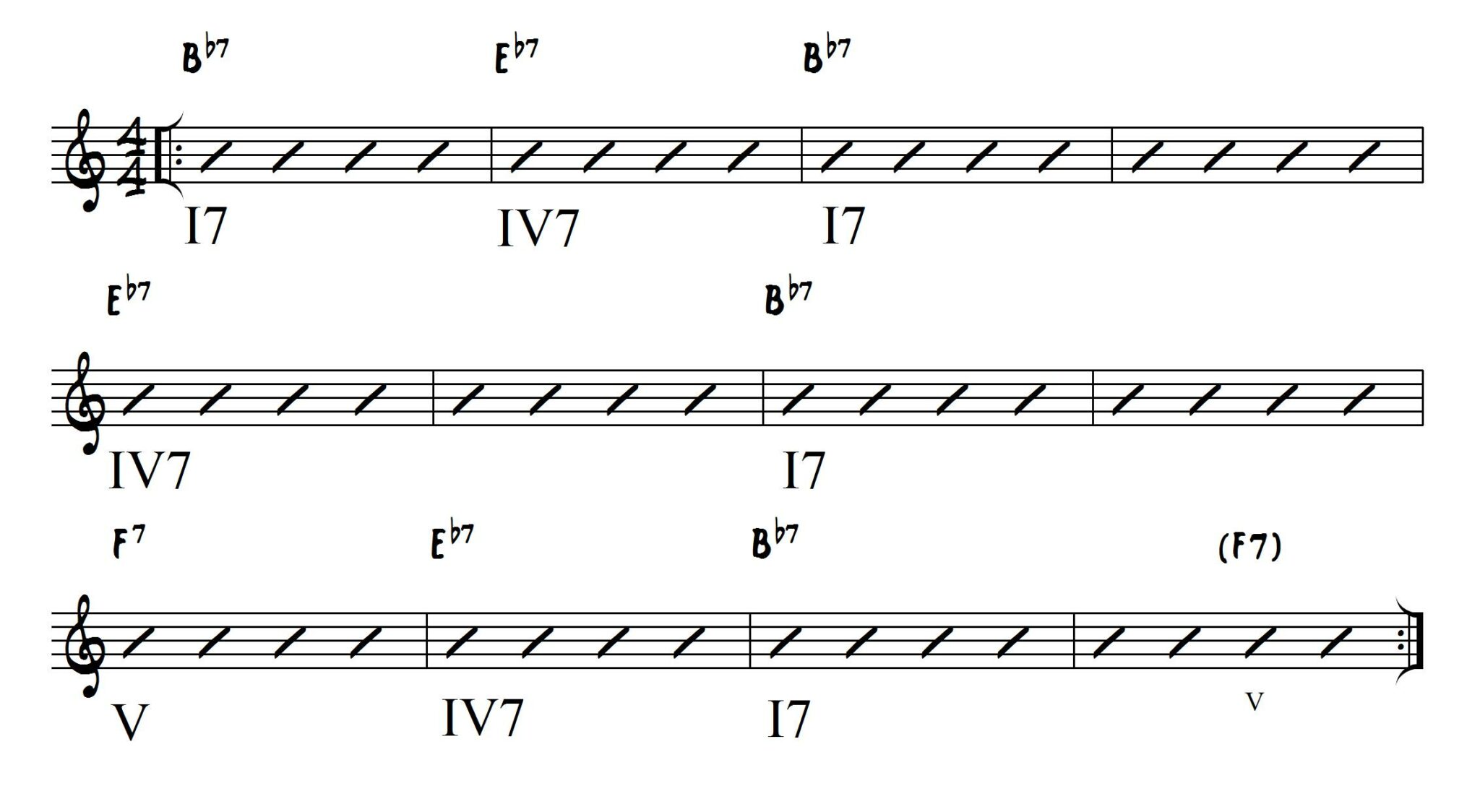

A different type of progression is the 12-bar blues. It is structured as follows:

I7-IV7-I7-I7

IV7-IV7-I7-I7

V7-IV7-I7-V7

An example of the Bb blues:

Note that there are many variations on the 12-bar blues. A key feature of this progression is the dominant seventh that is appended on every chord. Some examples include “Call It a Stormy Monday” by Stevie Ray Vaughan, “Roll Over Beethoven” by Chuck Berry, and “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley.

A staple progression in jazz music is the ii-V-I, also referred to as the ii-V-I turnaround. In this progression, the ii and V lead to the tonic, I. The chords of this progression are commonly played with sevenths (ii7-V7-Imaj7), and can be built upon further with upper extensions.

An example of the ii-V-I in C:

This progression can be incorporated into the blues.

| F7 | B♭7 | F7 | Cm7 F7 |

| B♭7 | B♭7 | F7 | Am7 D7 |

| Gm7 | C7 | F7 | Gm7 C7 |

Note: Cm7 and F7 are the ii and V of Bb, Am7 and D7 are the ii and V of G, and Gm7 and C7 are the ii and V of F.

The ii chord can be altered to create the progression II-V-I. The ii can also be treated as its own temporary tonic, extending the progression to iii-VI-ii-V-I.

The V7 chord can be substituted with the dominant chord built off of its tritone, the bII7, creating the progression ii7-bII7-Imaj7.

In a minor key, the ii7-V7-Imaj7 becomes ii7b5-V7-i7.

A variation on this progression is the “backdoor” ii-V, which approaches the tonic as follows:

iv7-bVII7-Imaj7

This is getting exciting. Our musical toolkit is growing. Next week, we will continue to explore the theory of musical harmony.

This is a bit random, but I actually thought about your blog today when I was listening to a piano solo over my airpods haha! Instead of just jamming and walking, I actually started to pick apart the different notes and chords, thinking about some of the topics you’ve covered! So, if that means anything, I think it means you’re doing a great job!

This week’s post is no different- you again presented the information in a clear, digestible way, and your passion for music and music theory shown through! Great job and keep up the good work!