The Claim

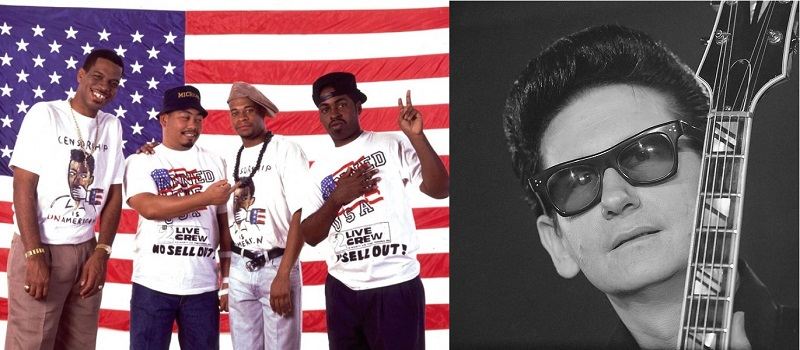

In 1990, Acuff-Rose Music, a music publishing company, sued rappers 2 Live Crew for their 1989 parody of the song “Oh, Pretty Woman.” Roy Orbis’s 1964 recording of “Oh, Pretty Woman” was already considered a classic at that time, and was revived by the 1990 feature film starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere. Acuff-Rose owned the rights to the song and previously denied a permission request for the parody. 2 Live Crew’s parody uses the melody and guitar parts from the original track, but changes the lyrics to a comedic encounter with two women on the street.

Roy Orbison’s original song, “Oh, Pretty Woman”

2 Live Crew’s parody, “Pretty Woman”

In their account of the long and rich history of parody in American culture, members of The Capitol Steps share their perspective on the cultural value of parody’s protection under Fair Use:

[I]t would be impossible to do parodies on breaking news if we had to get permission from the copyright holders. If we tried, we’d either get turned down or get tangled in lengthy negotiations about jokes whose shelf-life is sometimes measured in days. The copyright law, as we understand it, authorizes us to do topical parodies without getting anybody’s okay…. The simple fact is: Song owners, who nowadays are often either heirs or some large foreign-owned corporation, are seldom interested in offering up the straight line for somebody else’s punch line.

Bill Strauss and Elaina Newport of parody troupe The Capital Steps for The Washington Post

Similarly, a lawyer for 2 Live Crew asserted that fair use protection for parody was a critical free speech issue:

There’s an important First Amendment issue here. If you don’t give parody room to breathe, creativity will be stifled.

2 Live Crew lawyer Bruce Rogow

Lawyers representing Acuff-Rose claimed that the parody devalued the original song, and compromised their ability to license permission to use the song in the future.

Fair or Infringement?

Fair Use doctrine applies a four factor analysis to determine whether the use of copyright-protected content is allowable without obtaining permission from the copyright holder:

Nature and character of the use

- Transformative uses are defined as those that “add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work.” Did 2 Live Crew’s parody transform the original sample?

- Specific fair uses are actually mentioned in copyright law. They include:

- criticism

- comment

- news reporting

- teaching

- scholarship or research

Justice David Souter revealed the Supreme Court’s thinking as it weighed the four factors of fair use, stating that the nature and purpose of the use can be more influential than claims of effect on the market for the original work. This is significant, because that first factor of fair use is one over which content users often have the most control. In other words, content users can choose how, and how much, to transform copyright-protected content in their work, with the confidence that erring on the side of greater transformation is more likely to make their use fair.

The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

Supreme Court Justice David Souter in the Court’s opinion on Campbell v Acuff-Rose

Nature of the copyrighted work

- Creative works (musical compositions and performances) have more protection under fair use doctrine than technical works (musical scales).

- Unpublished works have more protection than published works; the original song was released by Roy Orbis in 1964.

Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

Regarding fair use factor three, Justice Souter observed that, while 2 Live Crew made substantial use of the ‘heart’ of the original song, that was necessary to achieve the transformative comedic effect in their parody:

When parody takes aim at a particular original work, the parody must be able to `conjure up’ at least enough of the original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable… If 2 Live Crew had copied a significantly less memorable part of the original, it is difficult to see how its parodic character would have come through.

Effect of the use upon the potential market for the copyrighted work

- Does the sale of 2 Live Crew’s album and other merchandise affect the potential market for the copyrighted work?

- Would the people who bought 2 Live Crew’s album or merchandise choose to buy the original song instead?

The Outcome

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that 2 Live Crew’s parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman” was protected under the fair use clause of copyright law.

The justices unanimously rejected a lower court opinion that said judges should assume commercial parodies are an unfair use of original works under federal copyright law. For the first time, the court stated clearly that parody, like other comment or criticism, could be considered “fair use….” Overall, the opinion written for the court by David H. Souter generously views the purposes of parody, saying that judges who hear copyright lawsuits should avoid rigid rules that would stifle creativity.

Joan Biskupic for The Washington Post

An interesting dynamic to the case was concern over whether Supreme Court justices had adequate knowledge about rap as a genre to make an informed ruling. This fair use case emerged at a time when many rap artists were defending their craft in court, not just for copyright infringement but also on obscenity charges. In fact, 2 Live Crew’s album As Nasty As They Wanna Be set off the series of court battles over obscenity in rap music in the late 1980s and early ’90s. (A decision calling their album obscene was overturned on appeal.) Indeed, some see the Campbell v Acuff-Rose ruling in favor of 2 Live Crew as a comeuppance for white musicians whose careers benefited from covering songs originally recorded by black performers.

Many black performers believed that covering undermined the longevity of their careers and even claimed unlawful appropriation of their very personalities.

Innovations such as the MIDI synthesizer permitted one to translate any body of sound, and particularly that to be found on analog recordings, into a form of code that could be inserted into a newly created composition. This allowed the entire recorded repertoire to be thought of as a kind of repository of ingredients that might be metamorphosed into something altogether novel and distinct from its constituent elements. African American musicians in hip hop particularly relished the opportunity to cut and mix the work of their predecessors….

One might say, by contrast, that such recordings, rather than simply covering another composition, instead uncovered qualities that heretofore were overlooked or inadvertently concealed.

Some rights holders, many of them music industry executives, expressed concern at the ruling, which shifted the balance of copyright lawmaking from creators’ control of their work toward users’ free speech rights.

This ruling strips musical authors, composers and songwriters of valuable property rights, elevating free speech to an absurd level.

EMI Music Publishing chairman Martin Bandier, in the Los Angeles Times

Campbell v Acuff-Rose also strengthened an important precedent in fair use case law – that of examining each infringement claim on a case-by-case basis, rather than relying on blanket decisions that would treat any commercial use of a copyright-protected work as infringement. In the case of the “Pretty Woman,” the “social value of parody as criticism” trumped the market value of future recordings. The 2 Live Crew victory is immortalized as a “significant liberalization” of fair use as the “primary safety calve of copyright law” when it comes to First Amendment-protected free speech.

The [Copyright Act of 1976] established a four-part [fair use] test that courts have subsequently grappled with by following the Gary Cooper rule of jurisprudence (good guys win, bad guys lose). The outcome has generally hinged on whether a parody harms the market for the original – which it seldom does…. If “making fun” is a “problem” for the music industry, their solution – to tangle it in litigation – is a problem for everyone else. The purpose of the copyright law is to encourage, not stifle, creativity.

Bill Strauss and Elaina Newport of parody troupe The Capital Steps for The Washington Post

Learn More

Strauss, Bill, and Elaina Newport. “What so Proudly we Flail: Parody as a Constitutional Right.” The Washington Post, Jul 04, 1993, p. C03, ProQuest US Major Dailies, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/307682394?accountid=13158.

Mauro, Tony. “Court’s Music Lesson: Rap, Rock and Rights.” USA Today, Nov. 10, 1993, p. C03, Nexis Uni, https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/92a9ceda-e833-4bc1-b9e8-8c5fd2ccf5ab/?context=1516831.

Soocher, Stan. “Supreme Justice: Rap’s Day in Court.” Rolling Stone, no. 669, Nov 11, 1993, p. 13, Music Periodicals Database, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/220148967?accountid=13158.

Biskupic, Joan. “Court Hands Parody Writers an Oh, so Pretty Ruling ; Copyright Law’s Fair use Standard Redefined.” The Washington Post, Mar 8, 1994, p. A01, ProQuest US Major Dailies, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/307713196?accountid=13158.

Philips, Chuck. “Ruling Allowing Parodies Shocks Many Music Execs.” Los Angeles Times, Mar 9, 1994, p. 2, ProQuest US Major Dailies, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/282219148?accountid=13158.

“Leading Cases” [see C. Copyright Law: Fair Use – Commercial Parody, pp. 331-341]. Harvard Law Review, vol. 108, no. 1, Nov. 1994, pp. 139-379. EBSCOhost, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7847283&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

“Affirming the Freedom to Spoof.” Chicago Tribune, Mar 10, 1994, p. 122, ProQuest US Major Dailies, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/418137759?accountid=13158.

Prowda, Judith B. “Parody and Fair use in Copyright Law: Setting a Fairer Standard in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.” Communications and the Law, vol. 17, no. 3, 1995, pp. 53-93. HeinOnline, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=http://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/coml17&i=229.

Sanjek, David. “Ridiculing the ‘White Bread Original’: The Politics of Parody and Preservation of Greatness in Luther Campbell a.k.a. Luke Skyywalker Et Al. v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.” Cultural Studies, vol. 20, no. 2-3, 2006, pp. 262-281, http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380500495742.