Last blog we dove into a little bit of the origins of today’s problems with the lack of room within cities, as well as a brief history of the American Dream and how it shaped zoning laws and modern demand for single-family housing. However, today we’ll be diving a little bit more into how and why single-family housing is bad for the environment while simultaneously creating an artificial housing shortage and other possible housing alternatives.

If you read the last blog, then you may know that building anything other than a detached single-family home is illegal (yes illegal) on approximately 75 percent of residential land in most American cities. This, in itself, is a problem. In the so-called “land of the free” why don’t we have more freedom to choose what kind of housing we want to live in? Well, as mentioned before in the last blog post, zoning laws that were developed60 years ago were adopted by the majority of American cities, which forced home builders to only build one type of generic, unsustainable neighborhood: single-family homes (SFHs for short).

Why and how are SFHs unsustainable?

Anyways, you’re probably asking this question by now. Well, it’s inherently in the word detached. It’s really not rocket science, the word just refers to how each house is per its surrounding houses, where there’s some sort of side alleyway or space between each of them. These spaces are redundant, and lead to more energy needed to cool in the summer and heat in the winter – primarily because two additional sides are exposed to the elements, letting heat escape easier. Also, more material is needed to build each house, compared to if two houses shared a common wall between each other. Not only this, but the fact that the majority of these homes have large, postcard-like front lawns simply means higher property taxes and maintenance costs for something that people rarely use in comparison to their backyards. These yards are arguably more of a status symbol than anything else, radiating the message “look at how much wealth I have, I can afford to have all this wasted space” when in fact, this way of exuberance is causing unnecessary habitat destruction while wastefully using resources.

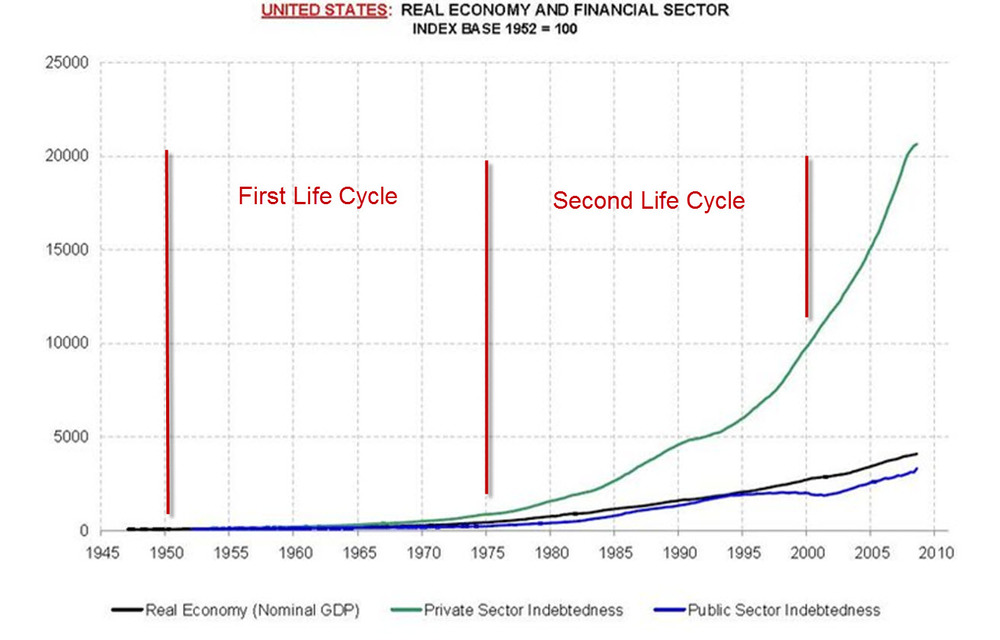

If you don’t care about the environment, then maybe you’ll care about money. Besides the houses themselves, modern zoning and city infrastructure around only building SFHs also creates a myriad of other problems, one especially being financially insolvent. For one – by virtue of their less dense nature – higher average lengths of road, sewage pipes, and electrical lines are needed in construction per house – and to connect them to their city’s grid. In the lifespan of these suburban SFHs neighborhoods, the upfront costs to the city government are relatively cheap due to the new massive amounts of cables and pipes being paid for by the initial homeowners, but once a couple of decades pass and the infrastructure starts to need repair, they induce huge costs on the city government. And because there’s so much infrastructure required for each house, cities usually don’t generate enough tax revenue per house to completely fund the repairs, leading the majority of US cities to incur debt.

If you don’t care about the environment, then maybe you’ll care about money. Besides the houses themselves, modern zoning and city infrastructure around only building SFHs also creates a myriad of other problems, one especially being financially insolvent. For one – by virtue of their less dense nature – higher average lengths of road, sewage pipes, and electrical lines are needed in construction per house – and to connect them to their city’s grid. In the lifespan of these suburban SFHs neighborhoods, the upfront costs to the city government are relatively cheap due to the new massive amounts of cables and pipes being paid for by the initial homeowners, but once a couple of decades pass and the infrastructure starts to need repair, they induce huge costs on the city government. And because there’s so much infrastructure required for each house, cities usually don’t generate enough tax revenue per house to completely fund the repairs, leading the majority of US cities to incur debt.

The easiest and fastest solution that most cities opt for is to just to allow for more SFH neighborhoods to be built, just for their quick, short-term tax revenues that they provide while ignoring the long-term maintenance costs that are the underlying issue. Another, less popular solution is probably one of the most straightforward solutions to this financial unsustainability which is to simply raise taxes to fund these repairs, but generally, this is unfavored by taxpayers/voters. So in essence, the SFH neighborhoods are part of a larger Ponzi scheme, primarily fueled by new construction of suburbs, and the quick tax revenue (“quick” as in a couple of decades) they provide to cities so they fix older, run-down neighborhoods and to fund their government functions. So if you were ever wondering why your city’s deficit is so high and is running a lot of debt, next time consider how your city has been planned.

However, some progressive cities across the US are starting to change this approach, opting for a more financially stable system that involves allowing multi-family housing to be built, that’s actually efficient in tax revenue and maintenance costs. For example in 2020, members of the Minneapolis planning committee are making it legal once again to build multi-family housing plans – such as duplexes and triplexes – citing their increased efficiency and affordability.

Ok, you explained how SFHs can be bad, but how are other housing options better?

We all know that consuming fewer things is generally better for the environment, and this also applies to housing; having less unused space and thus resources to build comfortable housing for people is just as important.

One prime example of great space usage is, of course, apartments. Although they aren’t the most desirable housing options in the US, they are the most energy and space-efficient. Generally, only one side of each apartment is exposed to the elements, saving occupants quite a lot of money on their heating bills. Apartments, of course, can be stacked, fitting more people closer to their jobs, and don’t require substantial amounts of infrastructure per capita to maintain, typically making them more tax-efficient, and tax sustainable for the city.

Although they do become more expensive and complex each floor they ascend, historically throughout the world the cost-effectiveness has been four to six floors of apartments – with new building techniques this has surely been increased. Apartments also do an efficient job at packing people together without destroying large amounts of habitat. For example, in the city of Amsterdam (internationally known for its urban planning), you can be in the heart of the city, and with a twenty-minute bike ride, you can be in the pristine Dutch farmland. In a typical suburban American city of a similar population, you’d have to spend a 30-minute car ride to reach the same, undeveloped outskirts. In this sense, denser cities are a win-win for everybody: farmers still have a lot of their land, more people can live closer to their jobs, and the population’s per capita carbon footprints are reduced.

Another, middle-ground approach are townhouses. They typically still offer the privacy of their own backyards, but the conjoined walls between the houses offer more heat savings and less wasted space, and thus less environmental impact. Townhouses also typically have smaller front or no front yards, allowing for more homes to be built per square mile. One downside to these are that residents usually still relyon cars for transportation, like nearly all suburban residents, due to them still being not dense enough for efficient public transit or walking and biking. Generally it’s not because people like to drive, but that it’s the most convenient to them.

Now to get to the point of this particular blog post, it should be noted that not all suburbs should be banned – but that Americans should have the choice to enjoy the overwhelming benefits of apartment lifestyles and better urban planning, instead of restricting this (on average per city) to roughly 25 percent of the city’s land and creating unnecessary housing shortages while forcing people to drive everywhere. Once again, the word count has hindered any further writing of this blog, but stay tuned next week for the finale of these political-sustainable themed RCL blogs!

If you’re interested by these posts, I highly encourage reading the TIME article below.

https://time.com/3031079/suburbs-will-die-sprawl/

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-02/inside-the-new-suburban-crisis

It’s true that single family housing negatively impacts the environment, but I think that’s true of any form of housing at all. Although you mentioned apartments as a more environmentally sustainable alternative, ignoring the increased benefits to QOL a person/family receives by living in a more wide open space such as the suburbs to exclusively focus on its problems is a mistake. If there’s a solution to the current housing shortage, I think that it’s pragmatic zoning deregulation. If it is more valuable to build multi-family housing upon individual plots of land (as is the case in many urban areas which are relevant to the argument you’re making), then developers will do so as long as they are allowed to. This will continue to be the case until circumstances change such that 50s’ style suburbs (or whatever is next in the future of single family housing) once again commands a premium price, at which time the current housing crisis will likely be resolved, or at least significantly diminished in severity.