The history of educational censorship in the United States is long and convoluted. Dating back to the First Amendment of the US Constitution, Americans are guaranteed, “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” This set a precedent for the value of freedom of thought in various public forums, including education. While education was still mostly privatized, there were few challenges to freedom of speech within schools and efforts to censor curriculum because wealthy parents had ultimate control over what their children were learning in private schools, and lower classes didn’t have the time or means to contest public school content. However, when public education spread across the country in the aftermath of the industrial revolution and child labor laws, issues of censorship and free speech started to emerge (Paterson).

In the South following the American Civil War, there was a mass effort to rewrite and restrict the teaching of history. This was pioneered by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who identified as the descendants of Southern Confederate soldiers. They were extremely successful in banning textbooks that contained accurate portrayals of slavery or that criticized Southern Civil War leaders, and were instrumental in creating a false “lost cause” mythology romanticizing Southern practices of plantation ownership and slavery (Halterman). In effect, accurate accounts of the Civil War were censored to preserve Southern pride.

Educational censorship has carried bigoted sentiments in other cases as well. The 1925 Supreme Court case Meyer v. Nebraska cemented the right of schools to teach foreign languages as part of their curriculum in response to a Nebraska law that prevented German from being taught in schools in the wake of World War I as a method of reinforcing cultural purity in America. A similar law in Hawaii that prevented Japanese from being taught was overturned in 1927 in Farrington v. Tokushige. Further panic over American students being exposed to foreign ideas took hold in the “Red Scare” 1950s, where there was a concentrated effort to avoid teaching students about alternative forms of government.

In many examples of educational censorship, there is an underlying current of fear. One of the most significant cases regarding censorship of curriculum and school libraries is Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico (1982). In it, members of the school board voted to remove a series of books from the school library for being “un-American”. A group of students sued on the basis of the 1st Amendment, and the Supreme Court ruled that, “…local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion’” (Justia). This precedent has since been upheld in cases like Counts v. Cedarville School District (2003).

However, the actions of various school districts and counties do not reflect this. There has been a growing movement for Parental Rights in Education, which claims that parents should have greater influence over public school curriculum in order to prevent their children from being exposed to content they do not wish for them to learn. In practice, this movement has been used to censor the perspectives of marginalized groups. This was seen in Anita Bryant’s 1977 campaign, “Save Our Children”, which targeted a nondiscrimination bill in Dade County, Miami, FL. The campaign aimed to prevent LGBTQ+ individuals from becoming teachers in order to “protect children” from their influence. In a similar vein, in 1993, the New York City School Board Chancellor, Joseph Fernandez, was ousted from his office after attempting to implement a “Rainbow Curriculum” in NYC public schools that included material preaching tolerance for LGBTQ+ people (Caruso). These are just a few examples of angry conservatives and parents effectively censoring curriculum and removing diverse perspectives due to “moral objections” that have given way to the onslaught of Parental Rights bills we now face.

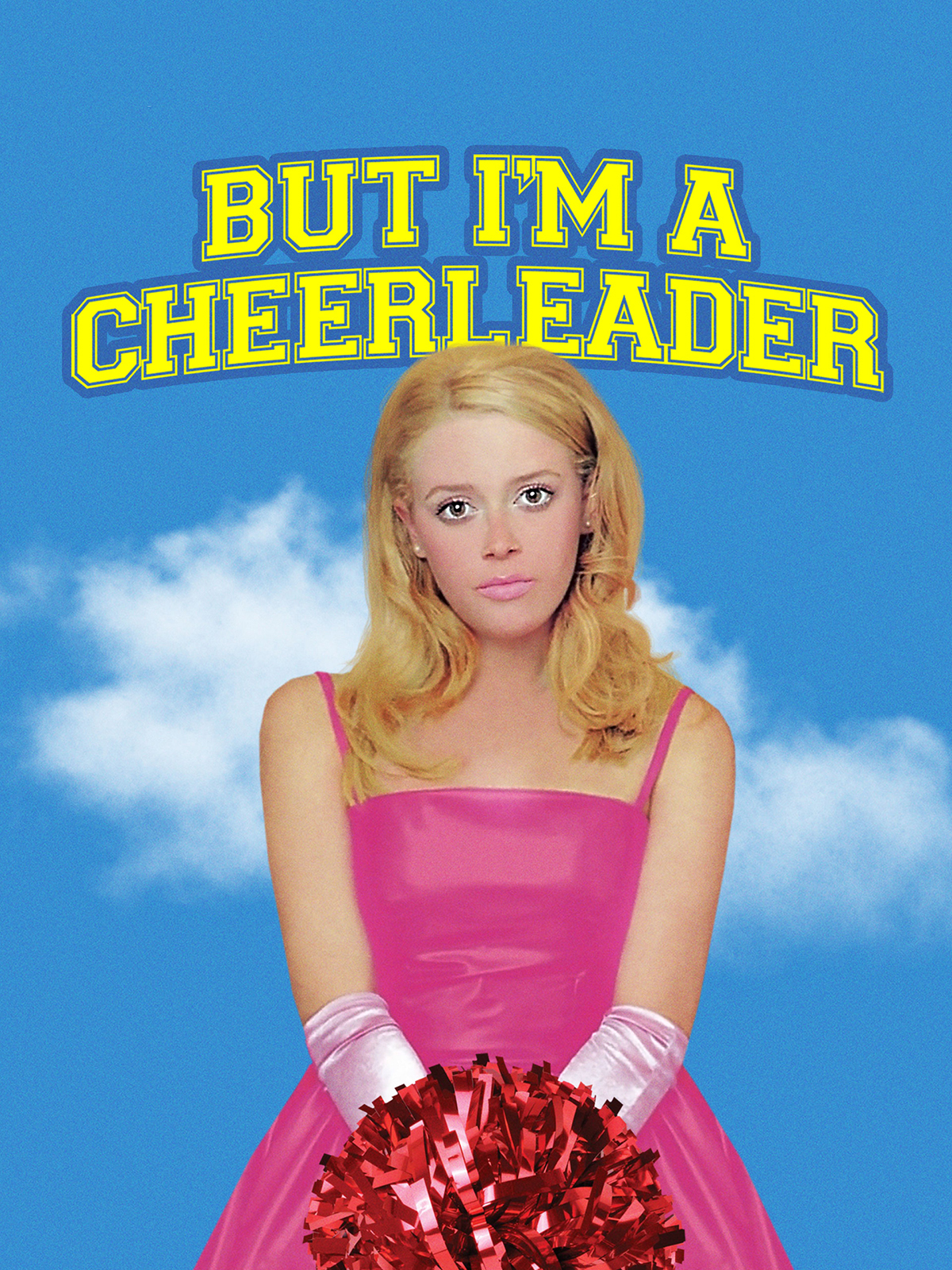

We still see all of these things today with attempts to censor educational material surrounding the Holocaust, climate change, Critical Race Theory and systemic racism, and LGBTQ+ literature. Proposed Parental Rights bills in states like TX, MO, VA, FL, MT, IN, IA, GA, and PA aim to do the same things that the board in Island Trees or the United Daughters of the Confederacy did. Throughout history, censorship has reflected a fear of narratives that empower the marginalized, and this is still true. That is why it is so important to combat.