For my third Civic Issues Blog, I have chosen to focus on the often discussed and disputed issue of college athletes receiving compensation or stipend in addition to scholarships. While athletic scholarships can take the large burden of paying for college off of the shoulders of the student, it is often argued that scholarships do not put food on the table. Many student-athletes come from low-income and middle-income families who rely on scholarships to put their children through college and ensure an education.

Another argument comes from the idea that college athletics are almost like a full-time job. Between the weight room, classes, film studies and practices, these students spend majority of their time (especially during the season) living, breathing, sleeping and thinking about their sport. In addition to the hectic life their athletic schedule poses, some students have to work jobs late at night just to have a little extra spending money for things not covered by the university. For example, extra money to see a movie or buy clothing not affiliated with the university.

The point is that a college scholarship does not equal money in the pocket (Huffington Post).

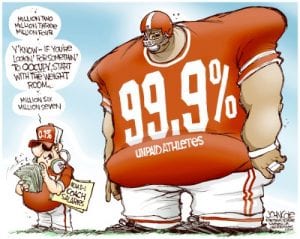

Even with any kind of scholarship, most college athletes are considered what we call broke. The top NCAA executives make close to $1 million a year, and the average coach makes around $100,000 a year; and what do the athletes make? Nothing. The coaches will receive bonuses for their teams making the playoffs, winning championships and breaking school records. What will the athletes receive? Nothing. The athletes are what ultimately bring in the money. So shouldn’t they be the ones receiving the compensation?

Unfortunately it is just not the case.

The NCAA also makes an absurd amount of money off of college athletics. Recently, the NCAA and CBS signed a $10.8 billion television agreement over ten years.

The NCAA is considered a non-profit organization. Let that sink in.

The athletic department also makes a sizable profit off of the achievements of their athletic teams. The department might be mentioned once after a championship run, but the team itself will be in the paper for the entire year.

The team will receive nothing in compensation.

The flip side, of course, is that not all teams make the same amount of profit, so it would be hard to pay each athlete the same. While I understand that, the money that the university makes from television agreements and licensing deals could be easily allocated towards their athletes.

Another argument is that these athletes are worth millions, so start paying them like it (Forbes). Universities expect a certain amount of professionalism from their athletes, however, they do not pay them like professional athletes. For example, Stanford’s star tailback and 2017 Heisman Trophy runner-up Bryce Love missed the Pac-12 media day in order to go to the extra classes he signed up for. Love, a human biology major, decided to take extra classes to graduate early. His absence at the pro-day was frowned upon, and he was criticized for his lack of professionalism as a star athlete. But he is, in fact, a student-athlete, and a prestigious university like Stanford should be applauding his efforts to go to class.

The truth is, athletes like Bryce Love bring in millions to their universities.

And coaches like Nick Saban are great, but the reason he gets paid millions of dollars is because of his ability to recruit athletes to play football at his university for almost free (Forbes).

Hopefully in the years to come there will be a solution to come out of all this debate. But until then, we can only hope that these student-athletes are able to juggle it all.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/artcarden/2018/07/26/college-athletes-are-worth-millions-they-should-be-paid-like-it/#504a09a2452e

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/tyson-hartnett/college-athletes-should-be-paid_b_4133847.html