For this Civic Issues Blog, I have chosen to focus on the rhetoric of the term “student-athlete.” As an often memed term, especially on sites like Twitter, the idea of a student-athlete is often boiled down to one certain stereotype. I think when society pictures a student-athlete, they see an extremely well-rounded individual, who is athletic as well as academically capable; and perhaps, a person who has it all. A person who is on top of their game at all times. A person who claims that “the grind never stops.” There are about 400,000 student-athletes who participated in athletic games this past year. For many collegiate athletes, the title defines them in every aspect of their life. Whether it be their athletic life, academic life, or social life, the term follows them everywhere. As someone who is not a student-athlete, I thought it would be interesting to do research on what the life of a student-athlete really entails.

It is a running joke among college campuses that much of a regular student’s tuition goes towards the elaborate backpacks and training gear the athletes receive and wear around campus. I must say, the jackets they receive at Penn State are really nice, but I am 100% aware that my tuition does not pay for their clothing. Still, it is fun to gawk at the nice gear they receive. I know that the athletes put countless hours of work into their sport, and they are among the best in their class. Thus, they probably deserve those really nice Winter jackets. I have friends from high school who chose to continue their prospective sports into college, and some even at the division one level. I have noticed that they also receive gear from their athletic department, but I often wonder how they balance it all, rather than the type of gear they are getting. I know college life is hard enough for a NARP like myself, so I wonder how they do it all. (FYI: The term that the athletes, or at least the people I know, often use to refer to regular students like myself is a “NARP”, or “Non-athletic regular person.”)

The truth?

The struggle is real for student-athletes. According to one student at Loyola Marymount University, a student-athlete’s life is consumed by school and sports. They are required to meet a certain GPA requirement to maintain eligibility, and if they fall below it they must attend study hall on top of their regular sports practices and study hours. In addition to this, most student-athletes can have little to no social life. Most of their time is consumed by classes, homework, practices and games.

Another scary truth?

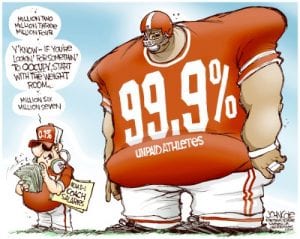

Only one in twenty-five student-athletes will go pro. And even if they do, there is no guarantee that the athlete will attain fame or be successful as a professional athlete. A striking statistic reports that 60% of student-athletes report identifying more with the term “athlete” rather than “student.” This is unfortunate due to the fact that a lot of the current student-athletes will never go pro, and therefore be behind their NARP peers in terms of job opportunities, education and experience in the work-field. A lot of coaches also do not follow the twenty hour per week practice limit, taking precious time away from their athlete’s studies, especially those who may be struggling in their academics.

The bottom line: student-athletes are really stressed out

Student-athletes report being more stressed than their non-athlete peers, and in most cases, rightfully so. They often feel high-stress levels in regards to schoolwork, extracurricular activities, practices, games, and sleep. Some student-athletes often feel other outside pressures, including needing to get a part-time job in order to pay for the things their athletic scholarship may not cover.

Personally, I have a lot of respect for the student-athletes. I played sports all throughout high school, and often felt stressed out at that level, so I cannot imagine what it must be like for them. I can only hope that it gets better for these athletes as time goes by, and that they are able to be successful in whatever their path may be.

The Struggle Is Real: How Being a Student-Athlete Is More Than Just Fun and Games

https://www.bestcollegesonline.com/blog/14-surprising-facts-about-being-a-college-athlete/