The Battles of Trebia and Trasimene are prime examples of Hannibal Barca’s great strategic successes against the Roman army. With the use of animals and tactical battle field strategy, Hannibal was able to decimate Roman armies that greatly outnumbered his own. Both of these battles are evidence of Hannibal’s military genius and the costs he incurred on the Roman army.

The Battle of the Trebia River occurred in 218 BC after a Roman retreat on the banks of the Ticinus River. The Roman general Scipio retreated back to the defended city of Placentia where he waited for a second Roman army to join him (Anglim et al. 164). Hannibal intentionally did not prevent this second army from joining Scipio’s numbers, as he intended to destroy as much of the Roman forces as possible (Gabriel 36). Hannibal showed even greater competence by using knowledge of his enemy to his advantage. Scipio was wounded at the skirmish at the Ticinus, thus Hannibal knew that this larger Roman force would be commanded by the general of the second army, Sempronius. Hannibal was more confident in his ability to trick Sempronius than Scipio (Gabriel 36). With his recent victory, a larger Roman force, and a less competent opponent, Hannibal set his plan in motion.

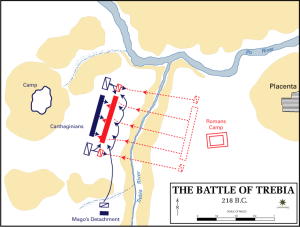

In order to surprise the enemy, he sent his younger brother, Mago, to take position in the cover of night along the banks of the Trebia River. Mago’s elite force of 2,000 calvary and infantry plus all of their weapons and horses were concealed in the thick brush along the river. The Carthaginian horses were trained to lie still on command (Gabriel 37). Beyond the steep banks which concealed Mago’s force was a flat treeless plain. The Romans would not be suspicious of the ambush (Lazenby 56).

At dawn, Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry and light infantry attacked the Roman camp at Placentia with a shower of javelins and missiles (Anglim et al. 166). Roman officers quickly woke their troops and hastily formed battle lines in response to the offensive maneuver. With the Romans awake, the Numidian cavalry drew back to a position previously chosen by Hannibal (Gabriel 37). Led by Sempronius, the Romans took the bait and pursued the Carthaginian forces right into Hannibal’s trap.

The bulk of Hannibal’s forces awaited the Romans on the other side of the Trebia River. Sempronius ordered his troops to wade across the river to engage with Hannibal’s forces in battle. The water was ice-cold and at times reached the chests of the Roman troops. Once through the freezing water, the Romans faced an uphill battle as they had to climb the sloping banks of the river. Hannibal’s forces held the upper hand before the battle even began. Now soaking, freezing, and fighting uphill, the Roman forces were at a disadvantage (Gabriel 37).

The Romans held their usual battle formation, with light infantry leading the way and cavalry protecting the wings of the infantry. The battle of Trebia is also an instance of Hannibal’s successful use of war elephants. Elephants were positioned in front of each Carthaginian calvary wing. The Roman horses were frightened by the foreign animals and fled, rendering the Roman calvary useless. Hannibal’s well trained calvary began to close in on the now exposed Roman flanks (Anglim et al. 166). Sempronius continued to push forward toward the Carthaginian center, as was usual for Roman warfare (and will play a huge role in later strategy for Hannibal). With the Roman’s now pushed into the center of Hannibal’s forces and surrounded on the flanks, Mago’s forces came out of hiding to ambush the Roman army from behind. The surprise of this new attack from another direction left the Roman formation in disarray (Gabriel 39).

Unable to retreat with Mago in the rear, and with calvary pressure on both flanks, the Romans were forced to continue trying to break through the center of the Carthaginian forces. Fewer than 10,000 of Sempronius’s 40,000 were able to reach the other side. They returned to their camp at Placentia (Lazenby 57). The remaining 30,000 were slaughtered by Hannibal’s forces or drowned in the Trebia in attempted retreat (Gabriel 39). Hannibal successfully inflicted massive destruction on the Roman forces at Trebia while only losing a few hundred of his own men. The greatest lost to Hannibal’s forces was nearly all of his war elephants which he had successfully employed in the battle of Trebia (Lazenby 57). This was a strategically important victory for Hannibal, as it occurred in Gaul. Because of this decisive defeat of the Roman army in their territory, Gaul rose up against Rome and joined the Carthaginian forces.

After the battle of Trebia, Rome is able to raise four new legions to replace those that were lost, due to a seemingly endless supply of soldiers from its allies. At the Battle of Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, Hannibal is again able to use strategy and knowledge of his enemy to outwit his larger opponent. His plan for this particular battle laid in his knowledge of Flaminius, who had a reputation for being hot headed and impulsive. Hannibal’s plan was to provoke Flaminius into an irrational move (Gabriel 39).

Near Tuscany, Hannibal made his forces visible to the Roman army there, but did not engage in battle. Instead, he chose to ravage the countryside, burn villages, and slaughter livestock. This served two purposes. First, Hannibal hoped that by devastating the land of the Roman ally, they would be convinced that Rome could not protect them and join his forces instead. This part of the plan was unsuccessful as the allies stuck with Rome. The second purpose was successful. The destruction of the countryside was enough to provoke Flabinius to pursue Hannibal (Gabriel 40).

Hannibal led his forces along the northern shore of Lake Trasimene. The path he followed narrowed, with the lake on one side and tall cliffs on the other. He led his troops along the path, which went up a steep hill. The Carthaginian forces set up camp on top of the hill and waited for Flaminius. While ascending the hill, Hannibal took note of a thick morning fog that decreased visibility on the narrow path beside the lake (Gabriel 40).

Using the advantages of his natural surroundings, Hannibal set up another hidden ambush. He placed his Spanish, Libyan, and light infantry in a semi-circle around the hills facing the lake. The calvary and Gallic forces hid in the folds beneath the ridges. As the Roman army passed through the narrow path, the infantry blocked the front and closed in on their left. The calvary moved in from the back. With the lake on their right, the Roman forces were trapped on all sides. Most Romans slaughtered or drowned in the lake, weighed down by their armor. Although approximately 6,000 Romans escaped the trap, over 15,000 died, including Flaminius (Bagnall 52). With the brilliant use of his natural surroundings, Hannibal yet again inflicted huge losses on the Roman army despite being greatly outnumbered. It is clear after the two great victories at Trebia and Tresimene that Hannibal was experiencing more than luck. His calculative planning led to strategic and decisive wins for his small forces.

His brilliant battlefield tactics continued to devestate Roman forces at the Battle of Cannae.