Nikola Tesla is the darling of many engaged science students; as an example of an audacious and endlessly inventive mind, he serves as a foil to Thomas Edison, the well-connected and established inventor who battled with him in the “War of the Currents”. The genuine risks involved in Tesla’s landmark experiments with electricity, his high frequency oscillator in New York City, and his conception of a directed-energy weapon give him a “mad scientist” aura that resonates with many. Elon Musk has taken this high-risk approach with his various companies, which most famously include Tesla Motors and Space X. It is yet to be determined whether this exciting strategy will pay off in the reliability-centered industries of automobile manufacturing and space travel.

Nikola Tesla, at age 34

Tesla was born in 1856 during a lightning storm in a village in the Austrian Empire. Both of his parents were Serbs, and he credits his mother’s inventions and genetics with sparking his innovative spirit and contributing to his eidetic memory. Tesla received his primary education at the Realschule, Karlstadt, where classes were taught in German. Soon afterwards, he nearly died from a bad case of cholera, which seems to explain his germaphobia as an adult.

After recovering, Tesla enrolled at the Polytechnic Institute in Graz, Austria. During his first year there, he reported studying 20 hours a day; letters sent home varied in sentiment from “Your son is a star of the first class” to warnings that he would literally work himself to death. Tesla developed a gambling problem after his second year and though he managed to win back the money he had lost, he never graduated from the university. In 1881, after working a couple odd jobs, he became the chief electrician at the Budapest Telephone Exchange and made several improvements to their system; it was during this period that he first conceived of the induction motor, which produces alternating current (AC) electricity by rotating a magnetic field. The next year, he moved to France and worked for the Continental Edison Company.

Tesla came to the United States in 1884 with a letter of introduction to Thomas Edison and little else. Edison hired him as an engineer at his company’s Manhattan headquarters, and Tesla quickly graduated to incredibly complex assignments, telling Edison he would like to completely redesign the company’s direct current generators. Apparently Edison offered to pay him $50,000 if he managed it, only to say he was joking when Tesla followed through. Tesla resigned shortly after that experience.

In the next few years, Tesla had financial difficulties but patented several new inventions related to alternating current. George Westinghouse became interested in Tesla’s ideas during his lecture to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, hiring him and licensing his AC motor patents.

Westinghouse went on to battle Thomas Edison’s General Electric in the “War of the Currents”, with Edison defending direct current by trumpeting the dangers of AC. He went too far, though, advising that a New York convict be executed with an AC-powered electric chair and secretly supporting Harold Brown, who publicly killed animals with alternating current. General Electric eventually overruled him and made large investments in AC electricity; Edison would later admit that he had been wrong about the potential for alternating current, which remains Tesla’s single greatest contribution to the world.

During this time period, Tesla invented the “Tesla coil”, which is still used in radio technology, and demonstrated the astonishing properties of alternating current at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893; Westinghouse Electric had underbid General Electric by $1 million to light the fair. The World’s Fair was a huge success and in 1895 Tesla was asked to design an AC generator for Niagara Falls. Soon afterwards, he released Westinghouse from his royalty payments for the AC motor to alleviate the company’s financial difficulties.

The Columbian Exposition at night

Much of Tesla’s early research was lost in a fire (not caused by him, surprisingly) in his 5th Avenue lab in 1895. At the time, he morosely told The New York Times “I am in too much grief to talk. What can I say?”

X-Ray of a hand, taken by Tesla

His research proceeded, though; he tentatively experimented with X-rays mere months before Wilhelm Roentgen formally announced their discovery in late 1895 and demonstrated radio communication two years before Marconi. He even envisioned a type of individual wireless communication that resembled modern smartphones and wireless Internet, though he did not receive the funding to pursue this or several other rather outlandish ideas.

In 1899, Tesla moved to Colorado Springs and conducted exciting experiments with electricity. He generated artificial lightning with million-volt discharges and thunder to match; the sound could be heard up to 15 miles away. One of his experiments accidentally burned out a generator six miles away, causing a power outage. He also experimented with a radio receiver, and may have heard transmissions from other experimental radio pioneers. However, he claimed that he was hearing alien communications, and this understandably damaged his credibility with the public.

Artificial lightning at the Colorado Springs lab; multiple exposure

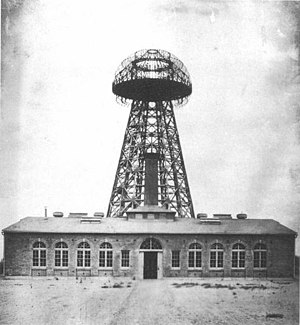

Wardenclyffe Tower

In 1900, Tesla began planning for his Wardenclyffe Tower facility in Shoreham, New York. Though J. P. Morgan funded much of the project, he refused Tesla’s subsequent requests for money to make a more powerful telegraph transmitter, partly because Tesla insulted him in his request by referencing the Panic of 1901, which Morgan caused. From that point onward, Tesla’s ideas steadily became more outlandish; in 1903, he asked Morgan for money to experiment with wirelessly transmitting electric power. It took Morgan a full year to reply and say no.

In 1912, Tesla matched the resonance frequency of several buildings nearby his Houston Street lab in New York City, causing a temporary panic. He also publicly discussed having constructed a directed-energy weapon, although it is doubtful that he actually had. Later in life, he took a great deal of comfort in feeding pigeons and even nursed one with a broken wing back to health. In 1915, Tesla received the American Institution of Electrical Engineers’ highest award, the Edison Medal.

Nikola Tesla’s name lives on as the SI unit of magnetic field strength and in the name of Tesla Motors, the car company led by Elon Musk. Both the company and Elon Musk reflect many of Nikola Tesla’s characteristics, such as his ambition, innovation, and outlandish ideas. Elon Musk’s biography is much more business-oriented than Tesla’s, but there are certainly parallels between them.

Elon Musk grew up in South Africa and taught himself to code, creating a computer game to sell by the age of twelve. He initially went to college in Canada and later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned two undergraduate degrees, one in economics and one in physics. He planned to pursue a PhD at Stanford, but dropped out after two days to launch Zip2 Corporation, which was an online city guide.

That company was bought out for hundreds of millions of dollars, and Musk made many millions more when eBay acquired PayPal, which he had co-founded, for $1.5 billion. Rather than settling down with his fortune, Musk went on to found SpaceX and Tesla Motors. SpaceX made history in 2012 as the first private company to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station, and it has made news several times with ambitious maneuvers. I still remember one of its attempts to land a reusable rocket on a docking station, which Elon Musk prefaced with a tweet saying that the chance of it working was less than 50 percent. To me, that experiment had a Tesla-esque aura about it.

This time, the reusable booster of a Falcon 9 rocket lands successfully

Tesla Motors is famous for making high-performance electric cars that can run for over 200 miles on lithium ion batteries. That may or may not be the future of environmentally friendly transportation, but it sure is futuristic; that’s the space Nikola Tesla tended to occupy. Elon Musk also helped to start SolarCity, the second-largest manufacturer of solar systems in the U.S., and promoted the idea of a Hyperloop, a high-speed transportation system that would be more efficient than any system currently in use.

A vision of the Hyperloop

Musk is also well-known for stating the goal of establishing a colony on Mars and saying that humanity is probably living in a computer simulation, from extrapolating recent technological advances into the future. These are a bit similar to the ideas Tesla had after 1900: they sound a bit crazy at first and they might have some merit… but they also might not.

Tesla Motors just reported a $22 million profit for the third quarter of 2016, which was a pleasant surprise for investors. As Timothy B. Lee of Vox put it, this “gives Elon Musk breathing room for his next act,” which is to prepare for production of mass market cars and include self-driving hardware in all of its cars, before the software for such technology is ready.

The risks here are fairly obvious. Scaling up production as a car company is much, much more difficult than as a Silicon Valley tech company (Tesla is already having some quality control issues); also, including technology that might not pan out in thousands of cars is a large risk, which might pay off and very well might not. However, Elon Musk does have plenty of experience with high-risk strategies, and it’s good to see a company with the name of Tesla embracing risky and futuristic ideas, no matter the outcome.

Tesla was a very interesting man, and I’m glad that science and history courses are beginning to pay him his proper dues. He truly made giant impact in the technological world. I liked the parallelism you draw between him and Elon Musk as well.