Under Barack Obama, the United States has been gradually normalizing relations with Cuba, potentially ending the five decades of hostility that preceded the Obama presidency. That hostility goes back to the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s, which was led by Fidel Castro and the doctor and revolutionary Che Guevara. I’ll focus this week’s blog on Guevara, because he has an interesting story that allows us to look at the U.S. from an outsider’s perspective. Also, I’m tired about thinking about Trump and this is a story I can tell without mentioning him at all. I could guess at the approach he’ll take toward U.S.-Cuba relations or make some overarching conclusion about populism, but I won’t.

Our protagonist was born as Ernesto Guevara to a middle class family in Rosario, Argentina in 1928. Guevara had an astonishing array of interests, intellectual and otherwise. Despite having severe asthma attacks, he excelled in sports such as rugby, soccer, swimming, and cycling. Much of his intellectual exploration was encouraged by his parents, who were politically left-leaning; his father welcomed Republican veterans of the Spanish Civil War into the home at various points, and their home was stocked with over 3000 books.

Guevara was passionate about poetry and thought-provoking literary works, by authors including Pablo Neruda, Federico García Lorca, William Faulkner, Franz Kafka, and Karl Marx. He also entered chess tournaments at the age of 12, having been taught to play by his father. Surprisingly, Guevara’s main academic interests were actually mathematics and engineering. In 1947, he moved to Buenos Aires to care for his ailing grandmother; the following year, he entered medical school at the University of Buenos Aires.

He’s probably older than 12 in this picture.

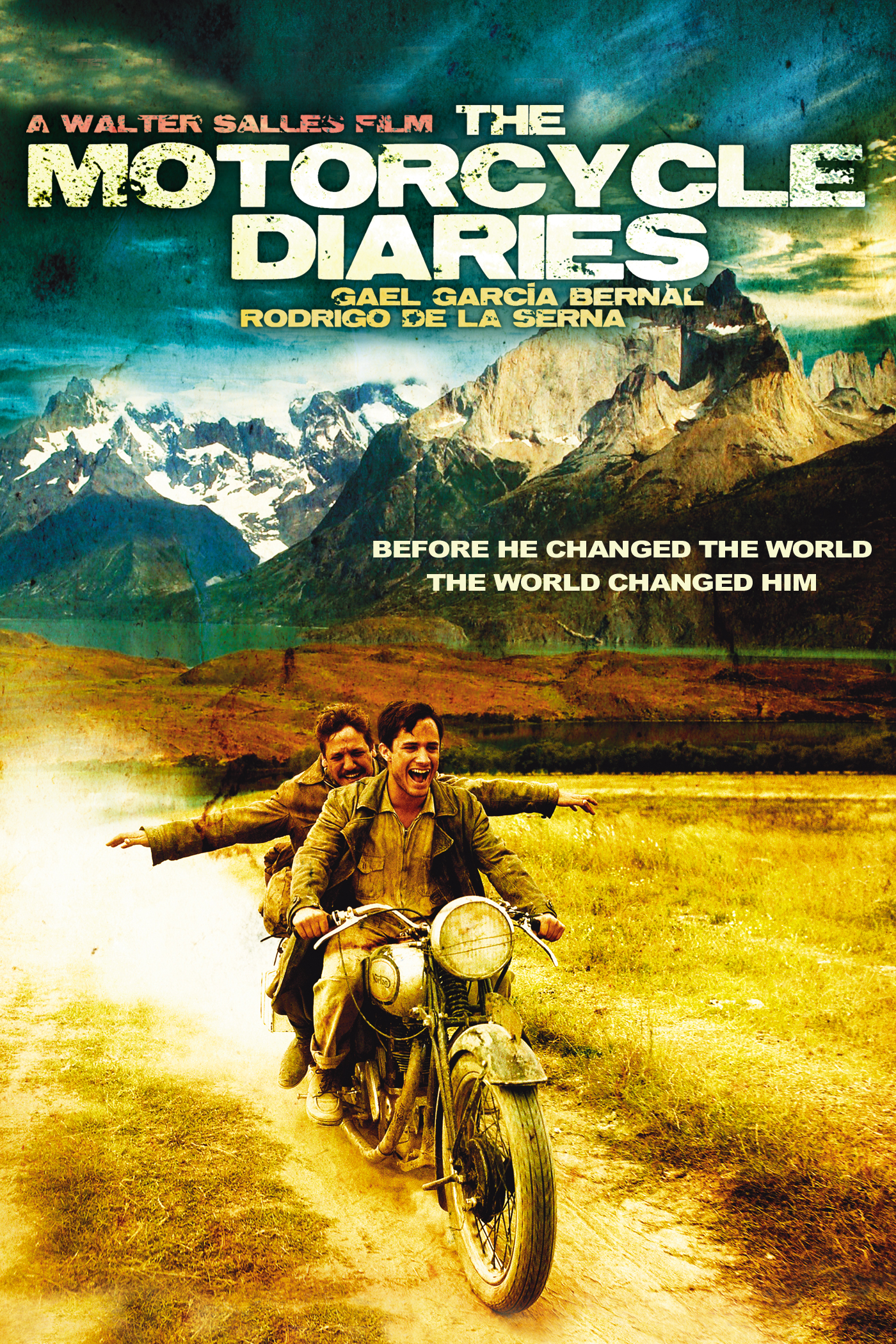

In 1950 and again in 1951, Guevara put his studies on hold to embark on far-flung expeditions throughout South America. In 1951, he and his friend Alberto Granado trekked across much of the continent, abandoning their motorcycle in Santiago, Chile partway through the 5000 mile journey. Guevara kept notes of his experiences on this journey and later used them for the bestselling book The Motorcycle Diaries, which in turn would be made into an award-winning movie in 2004.

During his journey, Guevara was struck by the poverty in rural Latin America and by the camaraderie he found in a Peruvian leper colony, writing “The highest forms of human solidarity and loyalty arise among such lonely and desperate people.” Guevara saw poverty and persecution in Latin America as a result of capitalist and imperialist exploitation.

After receiving his medical degree in 1953, Guevara again travelled northward and settled in Guatemala for a time, pursuing land reform under President Jacobo Arbenz in opposition to the mighty United Fruit Company. It was during this time that he acquired the nickname “Che”, a filler word he used often in conversation. In 1954, the U.S. forced Arbenz out of power and installed in his place a president who would crush unions, execute hundreds of suspected communists, and restore all United Fruit land holdings. Guevara attempted to fight, but there was no hope and he ultimately managed to secure safe passage to Mexico.

In Mexico, he met Fidel and Raul Castro and expressed willingness to take part in the revolution they were seeking to pull off in Cuba, known as the 26th of July Movement. The Castro brothers valued him for his medical skills, but he would become an important military leader after their original plans fell through.

In November of 1956, Guevara accompanied the Castro brothers and about 80 other revolutionaries in a boat bound for Cuba. They were attacked soon after landing, and fewer than 20 made it to the Sierra Maestra mountains, including the Castros and Guevara. There, they were aided by other guerilla forces and gained the support of many farmers. Guevara took special notice of the high poverty and illiteracy rates in the area and over time set up small schools, health clinics, and weapons factories. Fidel Castro soon promoted him to comandante, and he commanded his own army column.

Guevara became second-in-command to Fidel and used his power to keep strict discipline among his soldiers, ordering deserters and traitors to be shot, and also to teach them his love of poetry. He also inspired them with acts of insane courage; one soldier recounted such an event in his diary:

Che ran out to me, defying the bullets, threw me over his shoulder, and got me out of there. The guards didn’t dare fire at him … later they told me he made a great impression on them when they saw him run out with his pistol stuck in his belt, ignoring the danger, they didn’t dare shoot.

Guevara also helped to set up Radio Rebelde, the 26th of July Movement’s means of communicating with the Cuban people. As a military leader, he pulled off brilliant tactical maneuvers in numerous instances from the Battle of Las Mercedes in July 1958 to the decisive Battle of Santa Clara in late December of 1958. Following that final victory, he announced over Radio Rebelde that the revolutionaries had triumphed, contradicting the national news’s reports and hastening the Cuban army’s surrender. By January 1st, 1959, dictator Fulgencio Batista fled the country. Fidel Castro’s forces rolled into Havana on January 8th to claim the final victory, joining Guevara’s forces that had arrived six days previously.

Fidel Castro pictured. He died on November 25th, 2016, seven days after this blog was first written.

Soon after Castro came to power, it was decided that former Batista officials guilty of war crimes would be executed; over 90 percent of the public supported this. As commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, Guevara oversaw the execution of up to 500 people, mostly without due process. The international community generally condemned these killings, but Batista’s forces had undeniably carried out many atrocities against its own people and many of those executed were directly involved in that oppression. Many sources claim that Guevara also put innocent civilians before the firing squad and ushered in a police state in Cuba worse than the last (here, here, and here).

Guevara was subsequently placed in high government office and converted the Cuban economy to communism, which would not bring much success. His project to increase literacy was much more successful, bringing the literacy rate to 96 percent by sending out huge numbers of volunteer “literacy brigades.” He was also in charge of the militia training program that prepared Cuba to repel the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. After that, he send John F. Kennedy a note of gratitude, indicating that the attempted invasion had only strengthened the revolutionaries.

Guevara cultivated a stronger relationship with the USSR and was the primary force that brought Soviet missiles to Cuba, causing the Cuban Missile Crisis. When the Soviet Union backed down, he publicly criticized them for not taking the chance to attack the United States directly, demonstrating a dangerous level of commitment to his cause. Talk about being unfit to handle the nuclear codes! Not that I’m referencing Trump, because I promised not to do that.

The range capabilities of missiles stationed in Cuba

After a few years, Guevara was fed up with government work and left to spread communist revolution to other countries, such as the Congo and Bolivia. Both ventures were unsuccessful; Cuba had been a unique and unlikely case, and his confrontational style did not work well without Fidel’s restraint. In Bolivia, Guevara faced unexpectedly well-prepared Bolivian forces aided by the CIA and did not receive the help he was expecting from the Bolivian people; he fought for several months, but was finally captured on October 8th and executed the next day.

Che Guevara executed on October 9, 1967.

Che Guevara still appears on Cuba’s 3-peso note and Cuban students pledge daily to “be like Che.”

His iconic image represents audacity and revolution, but there is a more complicated story behind it. If anything, his story demonstrates to me the dangerous elements of revolution and its unwavering ideals. Guevara is just one example of how revolutionary ideals have led to (or almost led to) widespread bloodshed and disillusionment. It is understandable that the U.S. looked like the enemy to him, but advocating nuclear war is by no means acceptable. I admire his brilliance and resolve, but I have to think that in some ways he was a bit inflexible and misguided.

Iconic photograph by Alberto Korda

Thank you Alex for doing studies to write a balanced article on this historical topic of interest.

Yes I admired his brilliance and resolve as well but he was definitely misguided for sure.