This month, I’ll share the stories of famous scientists, starting with Galileo.

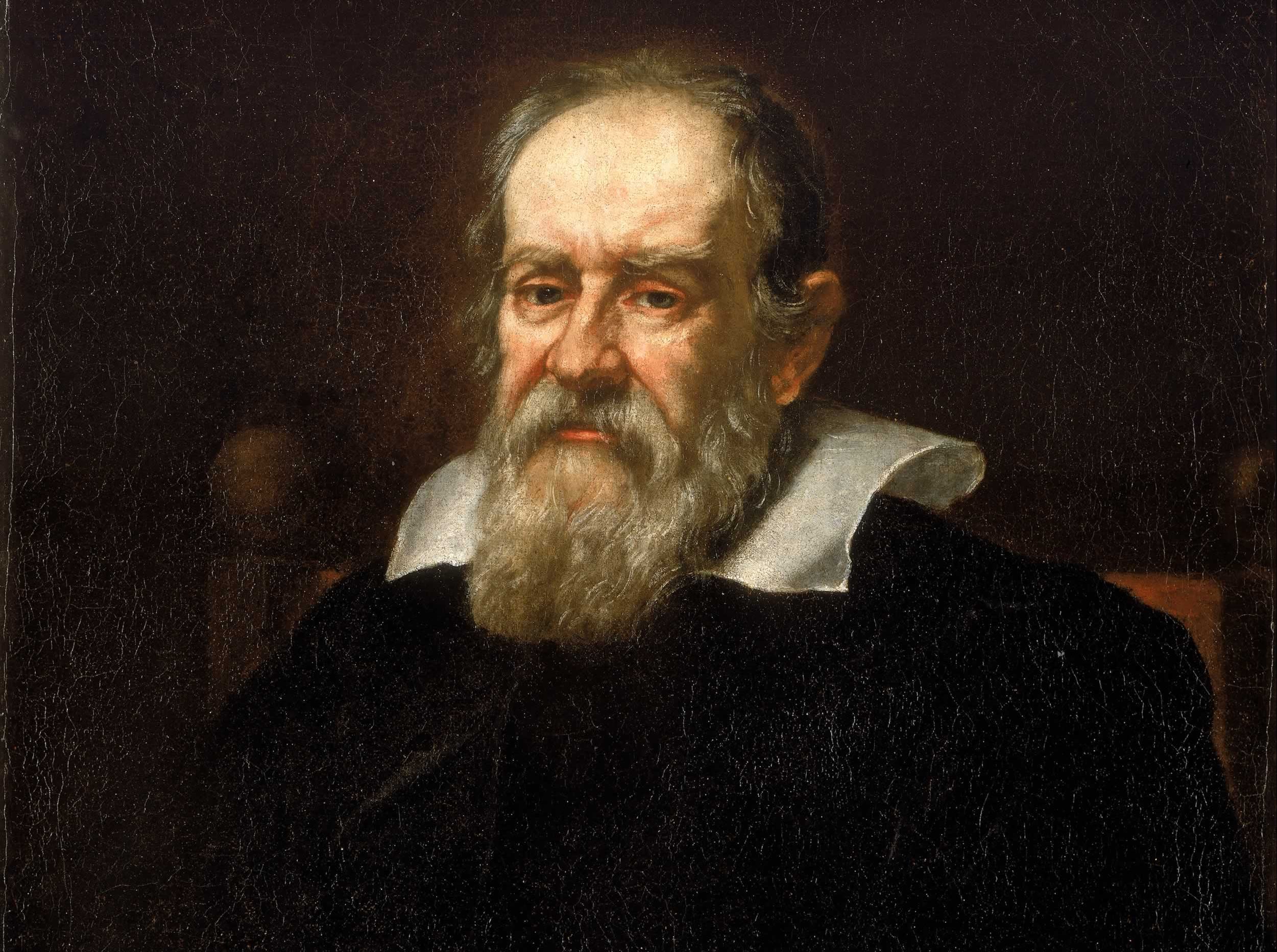

Galileo Galilei

Galileo was born in Pisa, Italy in 1564, the eldest son of musician and scholar Vincenzo Galilei. He gained an appreciation for music and science from his father, as well as a skepticism of authority. His formal education began at the age of eight; when his family moved to Florence, he was taught at a monastery near the city. He later considered becoming a priest, but his father urged him to pursue a medical degree instead.

Galileo entered the University of Pisa in 1581 for this purpose. However, he became quite interested in various other subjects, including mathematics and physics. In 1583, he noticed from the swinging of a chandelier that the time it took to swing back and forth (i.e. its period of motion) was independent of the distance it swung. He demonstrated this to himself with improvised pendula of equal length at home; raised to different initial heights, they swung with the same period of motion.

Galileo was on track to become a university professor but had to leave the University in 1585 before earning his degree, due to financial troubles. For many years, he supported himself with minor teaching positions while continuing to study and experiment with math and physics. One of those teaching positions was as an art instructor in Florence; Galileo admired the Renaissance artists of Florence and taught his students perspective and chiaroscuro (a style of contrast).

During this time, he published The Little Balance, describing a hydrostatic balance he had created. This gave him his first bit of fame in the scholarly world, and he was subsequently appointed chair of mathematics at the University of Pisa, in 1589. There, he conducted his famous experiments with falling objects and criticized Aristotelian views of motion.

His arrogance and unorthodox views led the university to let him go in 1592, whereupon he found a teaching position at the University of Padua, where he would remain for nearly two decades.

In 1604, Galileo began openly supporting the Copernican theory of heliocentrism and developed his law of universal acceleration for falling objects. It had previously been thought that heavier objects would fall faster (i.e. that acceleration depended on an object’s mass), but Galileo’s experiments disproved that theory.

Galileo learned of Dutch telescopes in 1609 and quickly improved on their design. Venetian merchants saw these telescopes as a way to spot ships at a greater distance and offered to pay Galileo to produce them; however, Galileo saw greater potential in his new creation. Using the telescopes to look out into space, he discovered that the moon was spherical, cratered, and mountainous; that Venus revolved around the Sun; and that Jupiter had orbiting moons.

Galileo’s telescope

Galileo published these findings in The Starry Messenger, and in an attempt to curry favor with Cosimo II de Medici, grand duke of Tuscany, he suggested that Jupiter’s moons be called the “Medician Stars”. I forgot to mention, he thought Jupiter’s moons were stars. Anyway, the book made him quite famous in Italy and Cosimo II actually did appoint him mathematician and philosopher of the Medicis, giving him a powerful new platform.

In the following years, Galileo published new works demonstrating further faults in the Aristotelian worldview. In Discourse on Bodies in Water, he described how objects float because of the differential between their mass and the amount of water they displace; in another work, he refuted Aristotle’s view that the sun was perfect by publishing his observations of sunspots.

When Galileo wrote a letter to a student saying that Copernican theory was compatible with Biblical teachings, the letter was made public. The Catholic Church disagreed with him, declaring heliocentrism a heretical idea and banning Copernicus’s On The Revolution of Heavenly Spheres in 1616. Pope Paul V personally warned Galileo to stop promoting Copernican theory.

From 1619 to 1623, Galileo was involved in a dispute with Father Orazio Grassi, a math professor at a Jesuit college. The dispute was originally over the nature of comets, but Galileo’s first response took care to insult the Jesuits and Grassi’s response was similarly combative. Galileo’s final retort was The Assayer, which was recognized as a masterpiece of polemical literature and also expounded upon many of Galileo’s thoughts on science itself. This is one of his quotes:

Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe, which stands continually open to our gaze. But the book cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and read the letters in which it is composed. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it.

Just as The Assayer was going to the press in 1623, Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, a friend of Galileo’s, became Pope Urban VIII. Galileo swiftly decided to have the book dedicated to the new pope, who was delighted by the gesture and by the content of the book. He encouraged Galileo to continue his scientific research and to publish on it, provided that he remain neutral on Copernican theory.

In 1632, Galileo published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. As the title suggests, it was a dialogue between characters about heliocentrism. Pope Urban VIII had requested that Galileo remain neutral and represent the Church’s view, and Galileo partially fulfilled that wish. In the book, there are three characters: one supporting Copernican theory, one opposed to it, and one who is impartial. However, the opponent of heliocentrism is named Simplicio (i.e. simpleton) and trips over his own arguments.

Galileo’s Dialogue

The Church summoned Galileo to Rome immediately, and he spent several months before the Inquisition. Though he was generally treated with respect, the Church ultimately threatened him with torture and forced him to admit that he had been promoting heliocentrism and to renounce the theory. He is rumored to have muttered “E pur si muove” (And yet it moves) after his apology and renunciation.

He was sentenced to house arrest for the remainder of his life, during which time he formalized his early discoveries about motion. He disregarded Church orders to take no visitors and publish no work outside of Italy; he managed to have his summary of his life’s work, Two New Sciences, published in Holland. The discoveries he summarized and expounded upon in that work have earned him the title “father of modern science.”

Indeed, Galileo’s trial before the Inquisition has also gained him fame as a sort of martyr for science, especially in the minds of Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire. Galileo’s advances in physics made Newton’s formulation of classical mechanics possible, a few decades later. Though not all of his hypotheses proved correct, Galileo certainly made great scientific advancements, especially in astronomy and physics, and was combative enough to leave us with a good story.

Galileo facing the Roman Inquistion by Cristiano Banti (1857)

Galileo is an interesting figure, because through most contemporary accounts, he was a brilliant individual, but was extremely arrogant in his work. While yes, he was right about most things he wrote about, he did not care to be tactful or understanding of other people’s beliefs. While I think for his situation, it worked out for the most part for him, but his arrogance could have led to his demise. Had he not had high ranking friends in the Vatican he likely would have been killed by the Inquisition.

You’re right, and he was just as arrogant and dismissive when he was completely wrong. He dismissed Kepler’s idea that the planets had elliptical orbits; he ridiculed the idea that ocean tides were caused by the moon’s gravity; and he argued that comets were just optical illusions. In every case he insulted his intellectual opponents in the process. So… he still had a good influence on history, but he’s probably another figure I wouldn’t want to interact with.

Your post covered a lot of information about Galileo that I don’t believe I have ever learned before. That was a nice change…you didn’t repeat the same facts that most people know about him due to his fame. The focus on his writing is particularly interesting. I liked his quotation the most; he was a scientist, but also very eloquent.

It was really interesting to hear to full story of Galileo. What would have happened if he had decided to become a prest rather than follow his father’s requests to go into medicine? I guess everything really does happen for a reason. I also like the story of the Chandiler. I never knew that that was why Galileo started thinking about pendulums.