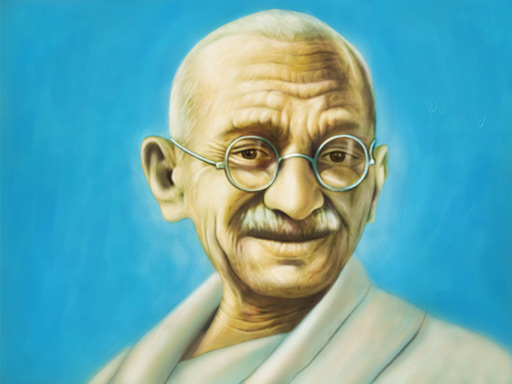

For my final month of passion blogging, I’ll write about political and military figures. Any guesses as to which figure will be featured in the final blog? For this week’s blog, I chose Mohandas Gandhi, because his name is famous but his complete story is not. Also, he is often called “Mahatma”, which means “great soul” in Sanskrit.

Mohandas Gandhi is remembered across the world for his nonviolent activism. As a leader of the home-rule movement in India, his most famous act was leading the Salt March, which protested a colonial law forcing the Indian people to buy heavily taxed salt. His philosophy of nonviolence has been adopted by many activists since, most notably by Martin Luther King, Jr and Nelson Mandela.

Gandhi was born in 1869 in Porbandar, India, which was part of the British Empire. His father was a fairly powerful political figure on a local/regional scale, and his mother was deeply religious. She practiced Vaishnavism (worship of the Hindu god Vishnu) and was also influenced by Jainism, an ancient Indian religion emphasizing nonviolence and self-restraint. Because of this, Gandhi’s family was vegetarian and his mother frequently fasted.

Gandhi participated in an arranged marriage when he was 13. Coincidentally, he was still afraid of the dark at that age and slept with the light on. Though he was shy, he became rebellious as a teenager, doing things such as eating meat, smoking, and stealing change from servants. That stopped when he was 16, when his father and first child both died.

Gandhi as a young man

Shortly after his second child was born in 1888 (when he was only 18!), Gandhi set sail for London, where he would study law. He had originally wanted to become a doctor, but his father had envisioned him becoming a government minister, and he had agreed to enter the legal profession to keep that dream alive. In London, Gandhi became more committed to his mother’s religious philosophy, studying the ancient texts of various world religions and joining the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society.

Upon returning to India, Gandhi struggled to launch his legal career. In his first appearance in a courtroom, he was so nervous that he forgot what to say, reimbursed his client, and fled. Eventually, he secured a contract with an Indian firm to work as a lawyer in South Africa for one year. In 1893, he traveled to Durban, in the South African state of Natal.

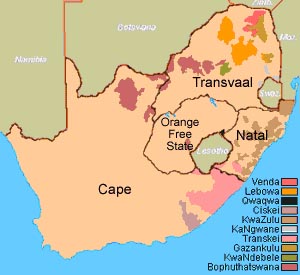

Natal region shown in east

He quickly discovered deep resentment and discrimination against Indian immigrants; in the span of a few days, he was asked to remove his turban in a courtroom and told to get out of the first class section of a train, even though he had a first-class ticket. In both cases, he refused to yield: in the first case, he left the courtroom; in the second, he was forcibly thrown out of the train compartment.

These incidents made Gandhi determined to fight against such prejudice. In 1894, he created the Natal Indian Congress for that exact purpose. When Natal passed a law banning Indians from voting, Gandhi stayed past his one-year legal contract to bring international attention to the law and demonstrate that the Indian community would not remain silent.

A few years later, Gandhi brought his family to South Africa with him and started a successful legal firm. He continued studying ancient Hindu texts and lived a simple and acetic life, much as his mother had. At about this time, he developed the concept of satyagraha (“truth and firmness”), his doctrine for nonviolent protest. He also led over a thousand Indian volunteers to join a British ambulance corps in the Boer War, demonstrating a willingness to make civic contributions in exchange for proper recognition and rights from the British Empire.

In 1906, he used the term Satyagraha for his first mass protest movement, which was against the Transvaal government’s new law restricting Indian rights (Britain decreed in 1900 that the name of the South African Republic be changed to “The Transvaal”). After many years of protests, the government jailed Gandhi and hundreds of other protestors in 1913; striking miners were also jailed, beaten, and sometimes shot.

However, the government relented to pressure from India and Britain and soon accepted an agreement negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts; the government’s concessions included recognizing Hindu marriages and abolishing existing poll taxes on Indians. When Gandhi returned to India the following year, General Smuts wrote “The saint has left our shores, I sincerely hope forever.”

In 1919, Gandhi led another Satyagraha protest against the Rowlatt Acts, which suspended civil liberties for Indian citizens. However, the protest ended in the April 13, 1919 massacre of Amritsar, in which British troops fired into an unarmed crowd of demonstrators, killing nearly 400.

Painting of the Amritsar Massacre

This atrocity turned Gandhi against the British; he returned his medals for military service in South Africa and encouraged widespread boycotts of British goods. Personally, he used a portable spinning wheel to make cloth for his own clothing, rather than buying it from the British. He soon became the leader of the Indian home-rule movement, and the spinning wheel became a symbol of Indian independence. Gandhi’s acetic lifestyle became famous, and his followers called him Mahatma, or “great soul”.

Gandhi was arrested in 1922 on sedition charges. Upon being released in early 1924 after an appendicitis operation, he found that the relationship between the country’s Hindus and Muslims had deteriorated. In late 1924, he underwent a three-week fast in an attempt to build unity between the religious groups.

In 1930, Gandhi protested the British Salt Acts, which prohibited the individual sale and collection of salt in India and placed a hefty tax on legal salt; salt was important in the Indian diet and this tax placed a large burden on the poor. He planned a 240-mile march to the Arabian Sea, where he could symbolically collect salt from the seawater, thereby breaking the law. He also dressed symbolically, wearing a simple homespun white shawl with sandals, and carried a walking stick. The march lasted 24 days and it sparked similar civil disobedience across India; about 60,000 people were arrested for breaking the Salt Acts, including Gandhi.

Salt March reaches Dandi Beach, April 1930

The Salt March made Gandhi known across the world, and he was Time’s 1930 “Man of the Year.” The following year, he negotiated the release of thousands of political prisoners and a slight loosening of the Salt Acts’ restrictions in return for an end to his Satyagraha protest movement.

Gandhi was imprisoned yet again in 1932, by new viceroy Lord Willingdon. From prison, he embarked on an effective series of hunger strikes to protest new laws electorally segregating the lower classes. He was only released in 1934, and in the following years he focused on issues of poverty and education.

In 1942, the British arrested Gandhi once again, along with his wife and other leaders of the Indian National Congress. His wife would die in 1944, before they were released. Because the Labour Party won the 1945 elections in Britain, negotiations finally began for Indian independence. Though Gandhi took part in the negotiations, he could not achieve his dream of a united India; it was partitioned into two countries, a predominantly Muslim Pakistan and a predominantly Hindu India.

As violence erupted between Hindus and Muslims, Gandhi went on another series of fasts and visited the areas affected by rioting. However, many Hindus began to see him as a traitor to their cause. On January 30th, 1948, Gandhi was shot at point-blank range by a Hindu extremist as his two grandnieces were helping him to a prayer meeting. He was 78. The following day, about one million people participated in his funeral procession to pay their respects.

.jpg)

Mohandas Gandhi’s funeral procession

Gandhi is rightly remembered for his philosophy of satyagraha and his efforts to combat discrimination and promote unity. In some matters, he was perhaps a bit naïve; for example, in 1940, he wrote a letter to Adolf Hitler calling him a friend and attempting to convince him to end World War II for moral reasons. Though he was probably naïve to appeal to Hitler’s humanity or to believe that nonviolent protest could be applied to any situation, Gandhi’s philosophy has had an undeniably positive impact on the world. It’s amazing what can be achieved by appealing to people’s humanity – as long as those people have more humanity than Hitler.

Mohandas Gandhi remains one of the most influential and revered figures long after his death. He is considered the father of the nation in India today, and even though Pakistan ideologically differed from Gandhi’s dream, it still recognizes all the work he did to ensure their freedom. My grandfather was just 8 years old when he partook in Gandhi’s funeral procession. His teachings transcended politics and are still used today; I have a framed quote of Gandhi’s hanging in my room.

I’m excited about this last series of posts, and that you started with Gandhi. It is so true that everyone knows of him but do not know his story. And I think it is such an important story to be told. I never knew that he was married at 13. And still needed a nightlight to sleep. Now being 19, that’s so crazy to think about. I also like how you included the humanity quote in the image. Nice job.

This story popped up on my Facebook feed a couple weeks ago in conjunction with some anecdotes about Mike Pence’s relationships with women, but here’s an element of Gandhi’s (sex?) life that I knew little about: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/thrill-of-the-chaste-the-truth-about-gandhis-sex-life-1937411.html

Really well written, as usual, Alex. You always pick people who are very much worth knowing about, but who few people do. This was a very thorough write-up of his life, although based on Kyle’s comment that we still don’t have the complete picture of him.