Martina Navratilova defected to the U.S. from her home country of Czechoslovakia to make her tennis career possible, and she was also one of the first major athletes to come out as gay. With the support of several friends, starting with Chris Evert, she would become a dominant player in women’s tennis and hold the number one ranking for years on end, in both singles and doubles. Navratilova faced a rocky path in both her personal life and in tennis, but nevertheless, she persisted.

Martina Navratilova was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1956, with the given name Martina Subertova. Her parents divorced when she was three, and she moved with her mother to a house just outside of Prague. At the age of seven, soon after her mother remarried to Mirek Navrátil, Martina practiced tennis every day under Mirek’s coaching. Eventually, she would take on his last name, with a female suffix, making it Navratilova.

Navratilova made large strides in her tennis game and began taking lessons from the Czech tennis champion George Parma at just nine years old. Two years later, in 1968, the Soviet Union led a Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia to suppress the Prague Spring. After Navratilova became the Czech tennis champion at age 15, the communist regime allowed her to compete on the Pro Tour, with the understanding that her success reflected well on their country and its government. In 1973, at just 16 years old, she was competing at tournaments in the U.S. and absorbing Western culture.

At the French Open in 1975, Navratilova finished second to Chris Evert. However, the Czech Tennis Federation garnished a large portion of her winnings, as was done in many Communist countries. Aware of Navratilova’s anger and troubled by her affinity for Western culture, the Czech regime put additional security around her and tried to prevent her from traveling to the U.S. Open that year. Under pressure from Czech Wimbledon Champion Jan Kodeš (who was too popular to be silenced), the government allowed her to compete in New York. At the 1975 U.S. Open, she reached the semifinals and did indeed defect to the U.S., leaving her family behind. Her press conference regarding her defection made for bigger news than the result of the men’s tournament.

Martina Navratilova discusses her defection (New York, 1975)

Though Navratilova initially had difficulties staying fit and focused, she received help from fellow tennis players, especially Chris Evert. They practiced and played doubles together, winning several championships. Their doubles partnership ended after Navratilova defeated Evert in the 1978 Wimbledon championship; from that point on, they had a great singles rivalry. In all, they faced each other 80 times, with Navratilova overcoming a large initial deficit to claim the overall edge, 43-37. Their styles were completely at odds: Evert was a calm and consistent player who thrived on long baseline rallies, whereas Navratilova was energetic and powerful and came to the net as often as possible.

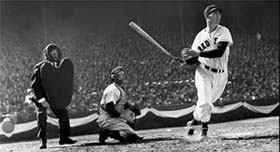

Navratilova wins Wimbledon, 1978

By 1979, the Czech government finally allowed Navratilova’s parents to meet with her. They met in Dallas, but her family was shocked by her lesbian relationship with the author Rita Mae Brown; in turn, they informed her of her estranged father’s suicide.

In July 1981, Navratilova was granted U.S. citizenship. In response, the New York Daily News published an interview in which Martina had mentioned her relationship with Rita Mae Brown. At the U.S. Open a couple of months later, she faced a lot of pressure as now-openly gay U.S. citizen trying to win her first U.S. Open. She cruised to the final, beating Evert along the way, but gave up a one set lead and lost the championship.

After losing to Evert 6-0 6-0 at another tournament in late 1981, Navratilova met Nancy Lieberman, a star basketball player, who influenced her to work harder on her fitness and her game. They lived together, but did not have a romantic relationship (Lieberman was heterosexual). Soon, Navratilova became extremely fit and strong, redefining the fitness goals of women tennis players. However, Lieberman also convinced her to develop a hostile mindset toward Evert and her other competitors.

Nancy Lieberman playing basketball

From 1982 to 1987, Navratilova won six straight Wimbledon titles and was the number one ranked player in women’s tennis. She finally won the U.S. Open in 1983, defeating Chris Evert in the championship. From 1983 to 1984, she won six straight Grand Slam titles, a streak that has never been topped.

Navratilova wins Wimbledon in 1983

In 1984, Navratilova’s friendship with Lieberman soured. She then met Judy Nelson, who encouraged her to see her competitors as friends rather than enemies. They moved to Aspen, Colorado together.

Judy Nelson and Martina Navratilova

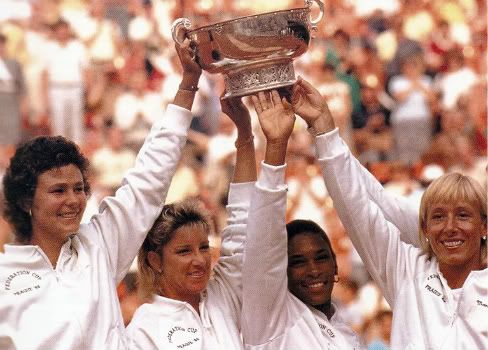

In 1986, Martina returned to Czechoslovakia to compete for the U.S. team in the Federation Cup. The people greeted her as a hero, though the government did its best to ignore her. The U.S. faced Czechoslovakia in the finals, and Navratilova competed for the U.S. in both singles and doubles. In her singles match against the Czech number one and reigning U.S. Open champion, Hana Mandlíková, the fans chanted “Martina” before the match and she went on to win 7-5, 6-1. She also won the doubles match with Pam Shriver as her partner, and Chris Evert won her singles match as well, giving the U.S. the Federation Cup title.

Team USA lifts the Federation Cup, 1986

A young German star, Stefi Graf, took her number one ranking in 1987. After that year, Navratilova won only one more singles Grand Slam title, the 1990 Wimbledon.

Steffi Graf wins the “Golden Slam” (four Grand Slams + Olympic Gold), 1988

Unfortunately, Martina’s relationship with Judy Nelson ended badly. After they broke up in 1991, Judy sued her for palimony and won half of her estate. For Martina’s friends, that malicious act outweighed any positive influences Judy had had.

Navratilova stayed in Colorado and began to speak out on political matters, including gay rights, animal rights, support for free speech, and opposition to Communism. This type of activism did not do her any favors in securing corporate endorsement deals, but eventually those worked out and she made a lot of money from her years of hard work.

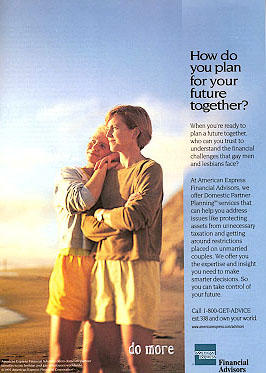

American Express appeals to gay and lesbian couples by featuring Martina

She continued to play doubles into the early 2000s, winning mixed doubles titles at the Australian Open and Wimbledon in 2003 and at the U.S. Open in 2006, when she was nearly 50 years old. At the 2014 U.S. Open, Martina proposed to her long-time girlfriend, Julia Lemigova (pictured in the ad above). They got married in December of that year.

Over the course of her career, Martina Navratilova won 18 Grand Slam singles titles, 31 major doubles titles, and 10 major mixed doubles titles. Her 61 combined Grand Slam titles places her second only to Margaret Court (with 64), who is a prominent anti-gay rights advocate.

Margaret Court

Navratilova completed a Career Grand Slam in singles, doubles, and mixed doubles (winning the Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and U.S. Open at least once in each discipline), making her one of just three women to ever do that (Margaret Court was one of the others). From 1982 to 1986, Navratilova went a combined 442-14 in singles, winning 12 Grand Slam singles titles (six of them consecutively) and holding the number one women’s ranking for all five years, in what is considered the most dominant stretch in tennis history. Martina Navratilova has overcome a lot in her lifetime, and she will be remembered as one of the greatest tennis players in history.

Navratilova, Evert, and Serena Williams at the 2014 U.S. Open