This is the second installment in my two-part series on philosophers. For this week, I chose a philosopher who better fits the description of a ‘historical character’.

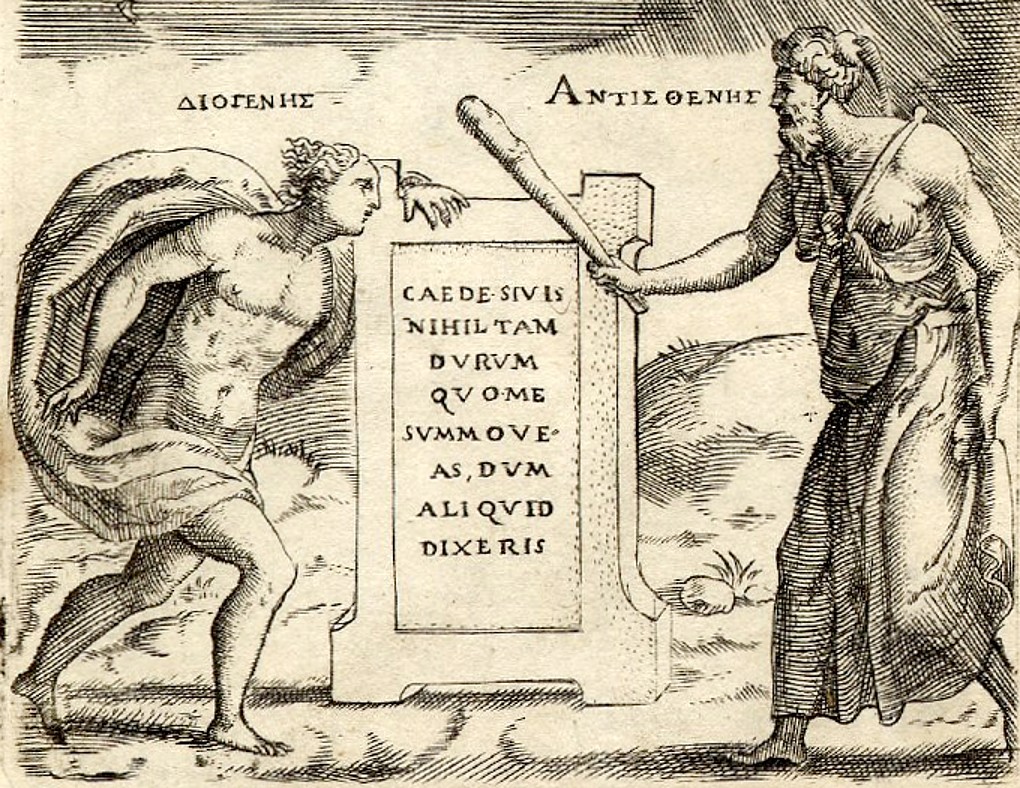

Diogenes the Cynic was a Greek philosopher who lived in the fourth century BC. When he was a young man, he and his father were exiled from their home of Sinope for defacing currency. Diogenes traveled from there to Athens, where he took up a life of asceticism and became a notorious contrarian. He supposedly badgered Antisthenes, an ascetic student of Socrates and the founder of Cynicism, to be his mentor (though Antisthenes may have beaten him away with a staff the first time he asked).

Detail from Giulio Bonasone’s Diogenes and Antisthenes

According to Cynicism, the purpose of life was to achieve happiness by living simply, naturally, and virtuously, without pursuing wealth, power, or fame. In practice (as we will see with Diogenes), this often led to criticizing other people’s ways of life. That has resulted in the modern understanding that someone who is “cynical” is jaded and skeptical of others’ motivations.

Diogenes’s written works have been lost to history, but fortunately he believed in teaching through action, and tales of his philosophical stunts survive. Whether or not he learned from Antisthenes directly, Diogenes’s illustration of Cynicism through his ascetic lifestyle and shameless stunts ultimately made him the more famous of the two.

In Athens, Diogenes lived in a tub (basically a large ceramic jar, turned on its side). By putting his simple lifestyle on display, he hoped to demonstrate that the physical and social structures of the city were unnecessary; he found social etiquette and taboos just as unnatural and restrictive as attachment to superfluous possessions. As such, he lived without shame, flouting cultural conventions and begging for food on the street. He is also reputed to have destroyed his only wooden bowl upon seeing a boy drinking from the hollow of his hands, remarking “Fool that I am, to have been carrying superfluous luggage all this time!”

Diogenes at home

Diogenes also performed stunts that conveyed his criticisms more bluntly. He frequently strolled through the streets with a lantern, in broad daylight. When asked what he was doing, he would patiently explain that he was searching for an honest man. Unfortunately, his search was in vain.

Statue of Diogenes searching for an honest man

Many of his stunts directly targeted Plato. When Plato was applauded for defining man as a featherless biped, Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato’s Academy, declaring “Behold! I’ve brought you a man.” Plato was thus forced to add something about “broad flat nails” to his definition. Diogenes also occasionally attended Plato’s lectures to distract those in attendance. At the root of all these antics was his unwillingness to accept Plato’s interpretations of Socrates; Socrates had also taught Antisthenes, whose ideas inspired Diogenes. So Diogenes and Plato can both attribute their ideas to Socrates (but Plato’s claim is more realistic).

Socrates and Plato in Raphael’s School of Athens

After many years, Diogenes ended up in Corinth. As the story goes, he was kidnapped by pirates while on a voyage to Aegina and sold as a slave to a Corinthian man. When the man, Xeniades, asked Diogenes what skills he had, Diogenes replied that he knew no trade but that of governing men (which apparently in ancient Greek sounded similar to “teaching values to people”) and that he wished to be sold to a man in need of a master. Xeniades was impressed and hired him to tutor his two children. Thus, even as a beggar-become-slave, Diogenes was the master.

Diogenes spent the rest of his life in Corinth, either continuing to work for Xeniades or as a free man (there are conflicting stories). He did not appear to resent his forced relocation from Athens; indeed, he was among the first to declare himself a “cosmopolitan”, a man not tethered to his country (or in the case of ancient Greece, a city-state), but rather a citizen of the world.

During his time in Corinth, Diogenes is said to have met with Alexander the Great. As the story goes, Alexander sought him out in his tub (possibly he was freed and found a new “home” in Corinth) and offered him any gift he desired. Diogenes responded, “You cannot give me that which you are taking.” Then, as explanation, “You are standing in my sun.” Fortunately for Diogenes, Alexander seemed to retain his respect for the old Cynic, recognizing that Diogenes was expressing his contentment with the simplest and most natural life available (that’s my interpretation, anyway). Alexander reputedly said he would rather switch places with Diogenes than with anyone else.

Alexander the Great speaking with Diogenes

Diogenes retained his logic and wit to the very end. On the subject of his own burial, he suggested that his body be thrown over the city wall so wild beasts could feast on it – provided that he be given a stick with which to defend himself. When asked how he could use the stick if he lacked awareness, he responded: “If I lack awareness, why should I care what happens to me when I am dead?”

Ultimately, Diogenes did a great deal to promote the philosophy of Cynicism through his various antics, as well as utilizing parody and satire to great effect. In turn, Cynicism inspired the philosophy of Stoicism, which would be founded by Zeno of Citium in about 300 BC (not to be confused with Zeno of Elea, who came up with several famous paradoxes). Stoicism would go on to become a major philosophical school in Rome, with Emperor Marcus Aurelius being its most famous practitioner.

Despite his accomplishments and entertaining exploits, I can’t say I agree with Diogenes on everything. Some of his fabled interactions demonstrate just why social conventions are needed: apparently, he once spat in a man’s face because the man told him not to spit in his house. I appreciate Diogenes’s role as a disruptive force in ancient Greece, but I wouldn’t be especially eager to interact with him or to see a society implement all of his ideas.

.jpg)