Napoleon is quite an interesting character, and his legacy is a bit mixed. On one hand, he made important liberal reforms, restored stability within France after the French Revolution, and was a military genius. On the other, he fought several wars with the rest of Europe that cost millions of lives and sought to control an empire that he ultimately could not.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David, 1805

Napoleon was born in 1769 on the island of Corsica. His parents, who had the last name Buonaparte, were minor nobility in Corsica, which had belonged to Genoa (an Italian city-state) until France took control of it in 1768. Napoleon attended school in France, learning French as his third language, and graduated from a French military academy in 1785.

His father died of cancer in that same year, and Napoleon returned to Corsica in 1786 as the new head of the family. He had become the second lieutenant of artillery in France, but in Corsica he found himself siding with the Corsican resistance to French occupation (ironic, considering his later expansion of the French empire). However, his relationship with nationalist leader Pasquale Paoli quickly soured and he took his family to France in 1793, where he changed their name to the French spelling, Bonaparte.

Once the Bonaparte family was settled in France, Napoleon rejoined his regiment in Nice. The French Revolution was underway at the time, and Napoleon showed his support for the left-wing Jacobins, among whom was Maximilien de Robespierre.

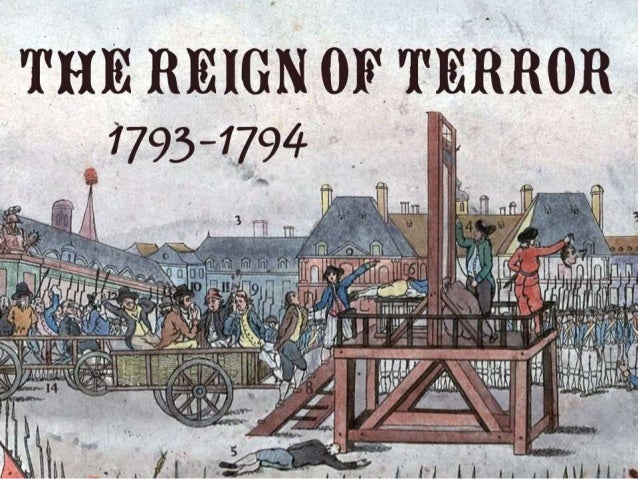

For context, the French Revolution lasted from 1789 to 1795 (possibly longer, depending on what is considered “revolutionary”). It began with Enlightenment ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité, but soon the country was swinging wildly from near-anarchy to the violent dictatorship of the “Committee of Public Safety”. During the Revolution, King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette were beheaded, and as many as 40,000 others were killed during Robespierre’s two-year Reign of Terror.

After the Reign of Terror, Robespierre himself was guillotined and Napoleon was briefly put under house arrest for his association with him. However, he regained favor with the Directory by suppressing royalist revolts in 1795, and in return he was made commander of the Army of the Interior. By the following year (at the age of 26), Napoleon controlled the entire Army of Italy, which was 30,000 strong. He quickly boosted its morale and won over a dozen straight victories against the Austrians in Italy. This resulted in French territorial gains at the 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio.

By this point, Napoleon was the most famous military figure in France. In 1796, he had further secured his heightened status by marrying Joséphine de Beauharnais, the widow of General Alexandre de Beauharnais. While he was commanding the Army of Italy, he wrote numerous love letters to her, but she nevertheless had an affair with a cavalry officer in Paris. Napoleon learned of this a couple of years later, during a military expedition to Egypt, and responded by immediately having an affair with an officer’s wife. He forgave Joséphine upon his return and they lived happily for many years thereafter, but Napoleon went on to have affairs with 22 women throughout the remainder of their marriage.

The Directory offered to let Napoleon lead an invasion of England, but he advised attacking the British trading network instead because of the strength of the British navy. That decision led to his 1798 invasion of Egypt, which was disastrous. He defeated the Egyptians, but the British under Horatio Nelson all but annihilated his fleet in the Battle of the Nile. That reinvigorated the enemies of France (Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and Turkey), who formed a Second Coalition and won back much of Italy. However, his troops did discover the Rosetta Stone during the Egyptian campaign.

Rosetta Stone

In late 1799, Napoleon returned to Paris and worked with a new Jacobin member of the Directory to engineer the coup of 18 Brumaire (named for its date on the Revolutionary calendar). He succeeded, creating a new government called the Consulate, and soon produced a constitution that provided for an all-powerful “first consul”. The constitution was readily adopted in February of 1800, and Napoleon was installed as first consul.

In June 1800, Napoleon drove the Austrians out of Italy, cementing his political power in France. He also secured a temporary peace agreement with Britain in 1802. That same year, he was made first consul for life by a constitutional amendment. In 1804, the Senate gave him the title Emperor and he crowned himself Emperor of the French in Notre Dame Cathedral.

The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David, completed 1807

In the meantime, Napoleon set about stabilizing and reforming France. He established the Concordat with the pope, which reinstated Catholicism as the official religion of France but retained the land and powers that had been taken from the church during the Revolution. He also instituted the Napoleonic Code, which streamlined France’s archaic, convoluted legal system and codified the Revolutionary values of freedom of religion, government hiring based on qualification, and the abolishment of legal privileges of birth. Furthermore, he commissioned and renovated a great deal of architecture in Paris, including sewers, reservoirs, bridges over the Seine, and the Arc de Triomphe, to name but a few.

Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, completed 1808

Though Napoleon was popular within France, he had many enemies outside it. With conflict looming in Europe and defeat imminent against rebels in Haiti, Napoleon sold the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States. In so doing, he raised 80 million francs ($15 million at the time, or about $252 million in 2017 dollars) for the French war effort and averted future conflict with the westward-expanding United States.

The subsequent wars in Europe from 1803 to 1815 would be known as the Napoleonic Wars. The first war lasted from 1803, when Britain and France renewed hostilities, to 1806. It was known as the War of the Third Coalition, as Napoleon fought a coalition of Britain, the Holy Roman Empire, Russia, and Sweden. Britain reaffirmed its dominance of the seas with the 1805 victory at Trafalgar, but Napoleon won the war on land with the successful Ulm campaign against the Austrians and especially with his “greatest victory” at Austerlitz against a combined Russian-Austrian force.

Napoléon at the Battle of Austerlitz by François Gérard

After the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon set up the Confederation of the Rhine, which consisted of all German states other than Austria and Prussia. This caused the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, which had existed for 1000 years prior to Napoleon and was considered the First German Reich.

In 1806, Napoleon began large-scale economic warfare against Britain through the Continental System, which decreed that French allies and neutral states were not to trade with Britain. This hurt the British economy, but it also hurt economies across the Continent and was difficult for France to enforce because of Britain’s naval dominance. The U.S. was also entangled in this trade war between Britain and France, which was one cause of the War of 1812.

Later in 1806, Prussia declared war on France because of its alarming influence among the German states, beginning the War of the Fourth Coalition. Napoleon immediately marched his Grande Armée into Prussia and defeated the Prussian army in a single month, capturing 140,000 men and various supplies in the process. The Prussians refused to negotiate a peace until the Russians had a chance to fight, though. After a few months and three bloody battles, Napoleon convincingly defeated the Russians as well. In the Treaty of Tilsit, he gave the Russians fairly lenient terms but took half of Prussia’s land.

Napoleon invaded the Iberian peninsula next, defeating Spain but starting a years-long Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal that would see guerrilla fighting and atrocities committed on both sides. Napoleon placed his brother on the Spanish throne, as he would do elsewhere.

The Third of May, 1808 by Francisco de Goya, depicting the killing of Spanish resistance members by Napoleon’s forces

Austria declared war on France in 1809, invading French-controlled Bavaria. After several large-scale battles and a few setbacks for Napoleon, he managed to defeat the Austrians and they signed yet another peace treaty.

In 1810, Napoleon divorced his wife, who had not borne him any children, and married Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria. The following year, she gave birth to a son, whom Napoleon promptly made King of Rome. That son is still referred to as Napoleon II, though he never actually ruled anything.

By 1812, Russia regularly violated the terms of the Continental System and was considering invading French territory. Ignoring warnings about invading the Russian heartland, Napoleon marched his Grande Armée toward Russia in late June.

Rather than facing Napoleon in large battles, the Russian army retreated deep into Russia. In September, they finally fought at the bloody Battle of Borodino outside Moscow that resulted in nearly 80,000 deaths. Napoleon then marched on Moscow, only to find it abandoned and burned. He had taken the Russian capital, but Russia did not surrender; in the French army’s retreat from Russia that winter, hundreds of thousands of French soldiers died.

Napoleon’s Withdrawal from Russia by Adolph Northen

The War of the Sixth Coalition soon followed, with Russia, Prussia, Austria, Sweden, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal all fighting Napoleon. He won several battles in Germany but eventually lost against a vastly superior force in the Battle of Leipzig, the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars, in 1813. Napoleon was offered fairly generous terms in Frankfurt in November 1813, but delayed in responding to them. They were soon rescinded, and though Napoleon won a few more battles, Paris fell in March 1814.

The Senate was persuaded to declare Napoleon deposed, so as to save France from the Coalition’s wrath. Napoleon wanted to march on Paris itself, but his generals refused, so he abdicated the throne. He was soon exiled to Elba, though he attempted to commit suicide with a poison pill first (the pill had lost its potency).

When rumors surfaced that he was to be sent to a more remote island, Napoleon escaped from Elba with 600 Imperial Guardsmen. He landed in France on March 1st, 1815, and traveled to Paris. King Louis XVIII, who had been restored to the throne, sent armies to arrest Napoleon. However, when he stepped out alone to face them, they instead joined his side. He arrived in Paris on March 20th and was welcomed as a hero; Louis XVIII fled, and Napoleon ate the dinner that had been prepared for the king.

Napoleon Returned from Elba, by Karl Stenben

The Allies soon met in Vienna and drafted a declaration of war against Napoleon, though he professed no interest in going to war again. In his “Hundred Days” governing France, Napoleon forgave the Frenchmen who had turned against him, allowed an opposition political to write a new liberal constitution, resumed public works projects that included the Louvre, and rehired various scientists and artists.

He had to quickly deal with the Seventh Coalition, however. In June of 1815, Napoleon led troops into Belgium to defeat Prussian forces. However, two days later, he lost to British and Prussian forces in the disastrous Battle of Waterloo, in which Napoleon made several errors. He returned to Paris, only to find that the French people and the legislature were both against him.

Painting of Battle of Waterloo

Napoleon abdicated once again and was soon exiled to the remote island of St. Helena by the British, where he was closely guarded and where poor conditions caused him health problems. After dictating his memoirs there, he died of stomach cancer in 1821, at the age of 51.

Napoleon on St. Helena

Napoleon’s legacy is still a bit murky, but after writing this blog, I have a more positive impression of him. It is inherently difficult to judge military commanders, who play highly consequential chess games that cause many deaths with each move. Perhaps this death and suffering cannot be forgiven, but Napoleon’s strategic skill is unquestionable; in his career, he won 48 battles, drew 5, and lost 7. In an 1806 battle, Frederick William III of Prussia retreated despite outnumbering the French 63,000 to 27,000 just because he mistakenly thought Napoleon was commanding the French.

Napoleon’s political skill was also remarkable. The Napoleonic Code, with its sensible codification of revolutionary ideals and streamlining of the existing legal code, was an incredible accomplishment. Napoleon’s support for the arts and sciences and creation of an education system made France an intellectual leader in Europe. His major mistakes, in my opinion, were pursuing the Continental System (which led to his invasion of Russia), fighting the costly, drawn-out Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal, and attempting to expand his empire beyond what was sustainable (or necessary).

And thus, we’ve completed our journey from Immanuel Kant to Napoleon, comandante. I hope it’s been somewhat enjoyable, or at least informative.

.jpg)