One of the most heavily debated topics regarding the Trojan War is, of course, its validity. Though the site of Troy was discovered (and subsequently hacked to bits) at the Hisarlik in modern-day Turkey (Werner), scholars still fail to come to terms with an acceptable conclusion regarding the existence of a Trojan War. Though several unearthed artifacts from the site, in conjunction with extrapolations taken from the text of Homer may point to a Trojan War actually taking place, a great deal of contradicting evidence exists.

The main red flag regarding the existence of Homer’s Trojan War is the fact that the epic poem, the Iliad, is brimming with a myriad of accounts of divine intervention: the interaction between deities and mortals. This representation of divine intervention can be broken down into two categories: divine intervention in 1) the structure and composition of the poem and 2) in the actual story itself.

1. Divine Intervention in the Structure of the Iliad.

As stated earlier, the Iliad is seemingly overflowing with divine intervention – so much so that the poem would seem to be incomplete and difficult to understand were it rid entirely of theistic mentioning. Therefore, it seems as if divine intervention is a large part of it’s essence. For example, an immediate mentioning of a “goddess” arises in merely the very first line of the first book. Shortly after, the god of the underworld, Hades, is mentioned. Then immediately after is Zeus, the king of Olympus. In that, divine intervention is written three times before the closing of the first strophe of the first book. The full strophe is given below with mention of divinities in bold.

“The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus’ son Achilles, the accursed wrath which brought countless sorrows upon the Achaeans, and sent down to Hades many valiant souls of warriors, and made the men themselves to be the spoil for dogs and birds of every kind; and thus the will of Zeus was brought to fulfillment. Of this sing from the time when first there parted in strife Atreus’ son, lord of men, and noble Achilles” (Hom. Il. 1).

So what does this mean? Well note that this is only the first strophe, indicating that much more is likely to follow. Therefore, divine intervention clearly plays a significant role in allowing Homer to illustrate his point. It enables him to captivate his audience, to interest them in the story he is telling. Therefore, one could argue that the deities is an integral aspect to the structuring of the poetry and allows the Trojan War to become a story that people would want to actually hear. This brings into question the reality of a Trojan War. Did it ever actually occur? If the bard reciting the events of the war needs to continue to refer to supernatural forces to make the war seem believable to the audience, could the war have happened?

How could referring to the unbelievable make the Trojan War more believable?

2. Divine Intervention in the Story of the Iliad

Divine intervention plays more than a role of structuring the Iliad; gods are an integral story. Throughout the Iliad, gods and goddesses interact directly with mortal beings, affecting their valor, strength, and morale.

For example, what kick-started the events that escalated into the Trojan War? The answer is Apollo, “(t)he son of Leto and Zeus; for he, angered at the king, roused throughout the army an evil pestilence, and the men were perishing…” (Hom.Il.1.10). The god Apollo himself was spreading a plague that affected all of the Achaeans. In the opening of the poem, Apollo has already affected every character to be discussed. That’s quite an intervention.

Take as another example the story’s archetypal hero Achilles. How does divine intervention affect him? He’s only the son of a goddess: “Mother, since you bore me, though to so brief a span of life, honor surely ought the Olympian to have given into my hands…” (Hom. Il. 1.351-353). The hero of the Iliad is constantly watched by a supernatural being who also happens to be his mother and was even dipped in the River Styx.

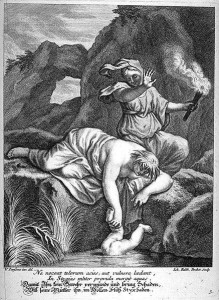

Achilles being dipped into the River Styx

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johann_Balthasar_Probst_003.jpg

As one last example, note the turning point of the Iliad and the Trojan War: when Achilles defeats Hector. After chasing Hector in a circle around the walls of Troy three times, Achilles is confronted by Athena, “…and standing close to him she spoke winged words: “Now indeed, glorious Achilles, dear to Zeus, I expect that to the ships we two will carry off great glory for the Achaeans, having slain Hector, insatiate of battle though he is; for now it is no longer possible for him to escape us…” (Hom. Il. 22.215-220). Thus, Athena appeared to Hector and convinced him to turn around and fight. This, of course, could be understood realistically with several different approaches. Perhaps Hector simply was hallucinating the image of Athena after running around the walls of Troy several times (Petersen p.5). Either way, were it not for Homer’s depiction of divine intervention, Achilles would not (or not as easily) slain Hector. All of these examples point to one thing: supernatural forces are so heavily involved in the story of the Iliad that the reality Trojan War seems all but ruled out if the divine isn’t involved.

All of these examples point to one thing: supernatural forces are so heavily involved in the story of the Iliad that the reality Trojan War seems all but ruled out if the divine is not involved.