Some of my favorite comics feature unlikely or unprepared heroes in real-world situations, caped crusaders facing rapists instead of mad scientists, or monsters, questioning what makes all of normal humanity so damned special. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a wonderful and oft referenced progenitor of this comic-book sub-genre, which has come to be recognized as being “deconstructionist”. Many of these stories, in fact, are derived from horror, as it is already rather unsettling.

In the argument for the literary merit of comic books, there would be no literary merit without deconstructionist books. They come in all shapes and sizes, but those that offer something interesting, a new take on a common storytelling trope, or a juxtaposition of two contrasting ideas portrayed in a new and unique format, will almost certainly enter the literary canon of any well-read hobbyist.

(why do all counter culture icons look like this?)

It is impossible not to talk about Alan Moore when discussing deconstructionist comics.

Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Miracleman, and my personal favorite, Swamp Thing, where he got his start. To explain the entire, one need only take a glance at the first two issues of Miracleman (later Marvelman), and the history behind them. Moore turned what started out as the British equivalent to Shazam (then, Captain Marvel(no, not that one)), into a hero who wasn’t remembered, cared about, needed, or taken seriously, even by his own wife, who blatantly and expositively deconstructs the entire superhero genre. That is the stage setting for the series, and it continues to go down a dark and very realistic path.

There are a thousand great deconstructionist books out there, and of of course I can’t name them all, but a great many of them warrant talking about and will be used later on in my blogs. Have you ever considered the fact that Joker is fine with murdering women and children, and we applaud Robin, a boy/teenager alongside Shazam, a 14 year old, for exposing themselves to that level of evil.

Mark Millar’s Sin City, which had at least one film adaptation, is generally accepted to differ from and breakdown the very essence of a comic book.

Rick Veitch was a man hellbent on exploiting his own industry, and will be blogged about later, but his work on Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, The Boys, and Brat Pack in particular, a realistic and dismal look at sidekicks, is some of the best writing in the history of comics, or so I hear (I haven’t been able to snag it for myself).

Moebius, while nowhere near as angry as Veitch, also warrants a blog devoted entirely to himself, but for the sake of doing what I said I would do, I cannot recommend Mad Woman of the Sacred Heart, along with Eyes of the Cat, by him and Jodorowsky, but I will talk more about those later on.

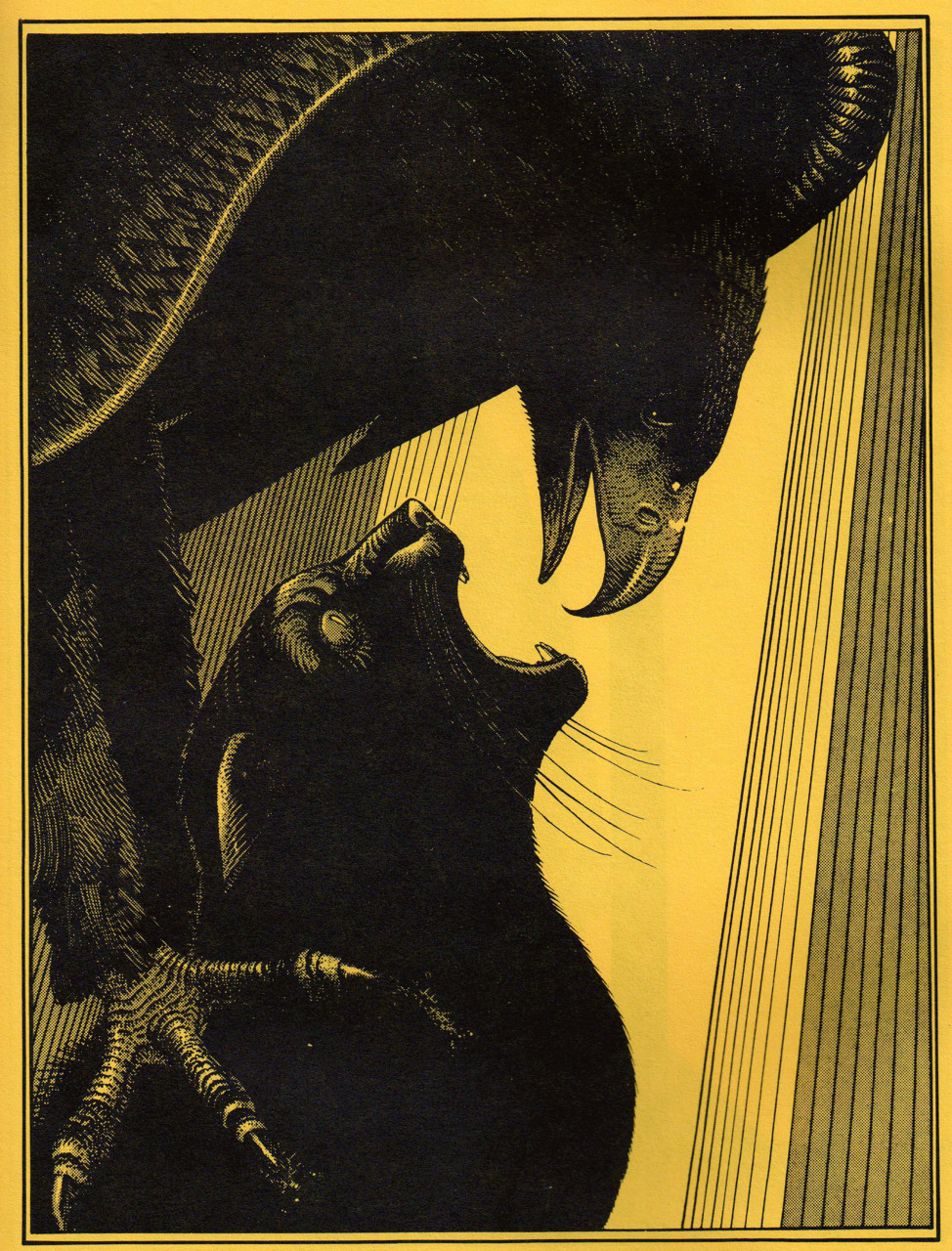

The art style tends to linger somewhere between realism and surrealism, with so much emotion and powerful meaning crammed into the coloring, costume choices, and especially background cover of each panel. It is the realistic nature of these books, realism in the form of self-reflective chaotic absurdism, that makes them feel more like plays, live performances in which the reader plays a part, rather than simple seventy cent comic books. They are undoubtedly among what some, I, might call comic caviar.

One small thing to remember, is that deconstruction pieces make commentary on their own genre. At the time that these books had their revolution, there were no cinematic universes, nor pop culture phenomenons. I offer that tidbit only as explanation for why certain aspects of some deconstructionist or adjacent pieces do not transfer to film. The subtlety is lost on a foreign media from the source material. The nuances of film differ from the nuances of live performance just as much as they do from a graphic novel.